The second part of a talk with Paul Zahl about Grace in practice — the first part of the talk can be found here.

Category Archives: The Zahl File

GRACE IN PRACTICE

Paul Zahl talks about Grace in practice. A brief addendum to the talk can be found here.

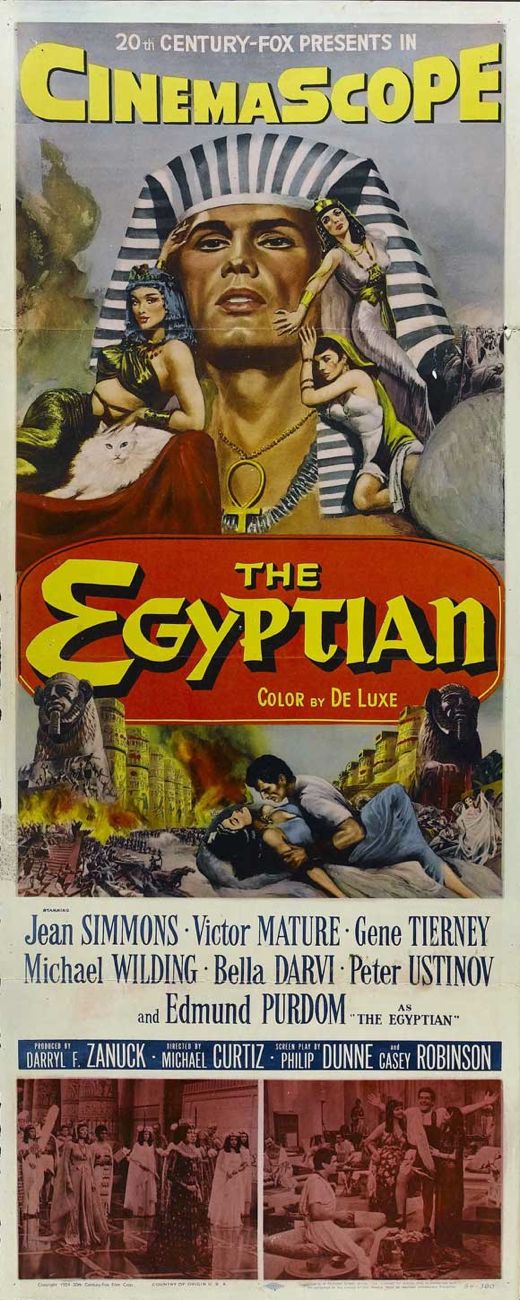

THE EGYPTIAN

This is not one of the great Hollywood epics but, boy, is it fun. If you watch it on a decent-sized TV in the Blu-ray edition by Twilight Time, the lunatic spectacle of it all will carry you comfortably through its general silliness. You can bask in the technical virtuosity of the 20th-Century Fox studio at its zenith, marvel at director Michael Curtiz’s elegant professionalism, and gaze in awe at what stars could do with less than stellar material . . . and at how non-stars, like the ill-chosen leading man Edmund Purdom, could be given a kind of imputed charisma by their surroundings. The whole thing is just a hoot from start to finish.

Elsewhere on this site Paul Zahl (of The Zahl File) has written a more sympathetic evaluation of the film — Walking In Memphis — with some fascinating observations on Jack Kerouac, who saw it when it first came out and hated it!

[Let me take this opportunity to apologize for the erratic formatting of many old posts here — the unavoidable by-product of a switch to a new blogging platform. I am trying to regularize the formatting of these old posts to the degree that it’s possible, but it will take me some time to get around to all of them.]

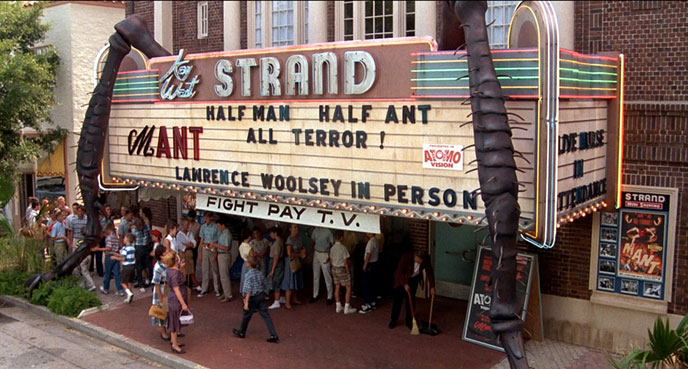

MATINEE

[Photo by Mary Zahl]

Above, Paul Zahl in front of the Cocoa Beach Playhouse in Cocoa Beach, Florida. Paul's visit to the theater, not too far from where he lives, in the Orlando area, was in the nature of a pilgrimage, since the Cocoa Beach Playhouse figured prominently in one of his favorite movies, Matinee by Joe Dante, where it doubled as the Strand theater in Key West:

There was a real Strand theater in Key West (now closed and turned into a Walgreen's) but for logistical reasons it was decided to dress the Cocoa Beach theater to represent it when Matinee was shot in 1993.

Matinee is a really enjoyable movie — check it out if you haven't seen it. Hard to find for many years, it was re-released on DVD in 2010.

LADY OSCAR

Here, Paul Zahl takes a look at an undervalued film by Jacques Demy, and finds much value in it, indeed:

HIS ODD BEAUTY

people seem able to say no to Jacques Demy's vision of life as reflected

in wonderful movies such as

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and Lola (1960). A phrase that seems to cover his vision is “optimistic romanticism”. Those are two good words for it.Demy

made several more films, however, and three of them,

A SlightlyPregnant Man (1973), Lady Oscar (1979), and Parking (1985) are

considered bombs. I've seen them all recently, though only segments of Parking, and can well understand their bad reputations.

But I disagree about Lady Oscar!

Lady Oscar is a beautiful movie, an opulent, visionary movie, about a

cross-dressing aristocratic heroine, played by Catriona MacColl, in the

Court of Marie Antoinette, who sees and hears the great events of the 1780s in her role of Captain of the Guards, while all the while loving the faithful, kind, courageous stable boy 'André Grandier', played by Barry Stokes.

The movie was directed and also partly written by Jacques Demy; and its lush, sentimental musical score is by Michel Legrand. Most of the actors were English but the film was filmed in France,

much of it at Versailles. An alternate title for the movie was The

Rose of Versailles.

The big stunner, when you

sit down and watch Lady Oscar, is the opening credit revealing that it

was Toho Studios of Japan that produced the film. At first glance, because of that familiar logo, you expect Mothra to come flying into the film. But

no, or rather, “Non!”: it's the fashionable, swirling, and almost

feminine style of the man who directed Catherine Deneuve, Françoise

Dorléac, Anouk Aimée, and later, Dominique Sanda.

In other words, this is a mélange, an improbable

mix of commercial and historical elements, which, taken together,

produced an odd movie — at least, if you stop to consider the

ingredients. Turns out Demy was not getting much work at the time; that the

Japanese had a popular commercial property on their hands, which was a

comic book entitled The Rose of Versailles; and that Lady

Oscar was made entirely and by design for domestic consumption in

Japan, even though it was filmed in France, with English actors, English

dialogue, and a French crew. Lady Oscar's being owned by Toho of

Japan is the main reason it hasn't been seen very often in Europe and

America — until now, that is, with the release in 2008 of a “Jacques

Demy Integrale” boxed set in France.

Long story, isn't it? Has all the makings of a colossal flop, right? Too many cooks spoil the broth, “n'est-ce pas”? You might think so. And many do. But I think Lady Oscar is a touching, lovely, sexy, beautiful movie.

Click here to continue reading and find out why:

THE ODD BEAUTY OF LADY OSCAR

Paul Zahl continues his look at Lady Oscar, an undervalued film by Jacques Demy:

HER ODD BEAUTY

First,

it is lovely to look at. There is not a bad or ugly composition in it,

for a master is directing the camera. As always with Demy, there is

the iris effect at the beginning and the end; the women's fashions are

gorgeous; the lens is fluid but not falsely fluid. (I love the Vertigo

effect, half-way through, when Marie Antoinette finally succumbs to her

“youthful passion” in the garden pavilion. It doesn't feel out of place

at all.) The ball sequences are fairy tales of movement and pastels,

especially blues; the outdoor scenes at the Queen's Versailles hameau

or retreat are pure “70s pastoral”, soft-focus, but not like

advertisements; and the actors, who are mostly wooden, fit when you

understand they are meant to be decoration for . . . “Lady Oscar”.

Now I come to the two chief goods of this film,

which leaves, with its many faults — such as the woodenness of the

plot, the script, and the actors, to name just a few! — a lasting impression.

The first great plus of Lady Oscar is the

“gender-bending” situation of the main story. “Lady Oscar”, a daughter born

to a noble mother after five girls have preceded her in birth, has been raised a boy. Oscar is a beautiful young woman in the

garb and robe of a young man. But Oscar knows she is really a girl, and

understands herself to be a girl. Nevertheless, she plays

the part of and dresses like a man, in order to please her father (who

had tired of having so many daughters, and longed for a son).

There

is no sub-text here, in other words, or at least none that I

can see. When Oscar takes off her shirt, for example, to examine her

body after a duel, we see her female chest. Demy dwells on Catriona

MacColl in this scene. Later, she is able to confess her lifelong love

for 'André' to André, and they make love. There is no ambiguity or

ambivalence.

Yet,

and I think it is an important “yet”, “Lady Oscar's”

role-playing, her

male clothing over a woman's body, gives her insight and involvement inthe life of both the sexes at Court. We therefore see the highest world of female fashion,

through the eye of the Queen's Body Guard, “Oscar”, who is a woman. Maybe

this reflects Jacques Demy's own persona. I don't know. He certainly

shows, in the stunning visuals and moving camera, a secure comfort with

the material.

Whatever is going on under the surface, or

psycho-dynamically, on

which we might have more light to shed today, what you actually see in

the movie is the tale of a yearning female adult who is doing her duty

(and performing it well) as a cross-dresser, yet never stops loving . . . André.

Now to the second and final point, the core of “Lady Oscar for Today”. A

theme I see again and again in the films of Jacques Demy is the

contrast between private domestic intimate drama, between individuals;

and the bigger social and political struggles that surround people at

points of history. Thus, in The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), the

romantic longings of the twins, played by Catherine Deneuve and Françoise

Dorléac, are lightly contrasted with readings

from the newspaper, by their mother, concerning threats to world peace. In A Room in Town (1988) the fated

romance of Dominique Sanda and Richard Berry is played out against the

background of a shipbuilders' strike in a French port. The

focus is on the intimate drama, not on the social conflict; and that is

reflected concretely and bitterly at the end.

scenes, such historic events as the first meeting of the Estates General

and the fall of the Bastille, the director's focus, almost

against the screenplay, is on “André” and “Oscar”. That relationship is

where your emotional attention is, from the beginning to the end. And

the ending of the movie reflects this personal focus most

acutely, and painfully, and memorably. No wonder almost everyone

deplores the ending. I can well understand why. Nevertheless, I love

the ending. Mainly because I can't shake it. I wake up sometimes

thinking about it, crying out “André!” and waking our neighbor's dog,

not to mention Mary.

The ending of Lady Oscar says something

important about life. The “devil is in the details”, or rather, the

heart of life is in the personal — the intimate, the one-to-one, the

“hopes and dreams of all the years” . . . in a gently crying child, in

a

mourned romantic love, in a blue-and-red uniform of the Queen's Guards,

with a lovely actress secure within it, looking not for “Liberté!

Fraternité! Égalité!” (which are wonderful ends,

we know), but rather for the stable boy of her heart, the man whose heart

never left her and whose heart she never left.

LARKING ABOUT

Whenever we get together my friend Paul Zahl and I like to amuse ourselves by collecting severed heads in sacks — an activity that's not as easy as it sounds! This summer we had a few very successful collecting expeditions — no records set but lots of fun all around!

BUFFS

My nephew Harry and my friend PZ discussing movies — the subject here, Kurosawa!

SOUTHERN LADIES

My mom and my friend Mary Zahl discussing smocking in the living room of my sister's house in Hampstead, North Carolina.

ON THE ROAD: PZ PODCASTING

Paul Zahl in the Winter Garden, Florida studio where he records PZ’s Podcast. Here he’s cuing the 100-piece studio orchestra for a dramatic sting to underscore a salient point about the intersection of Protestant theology and the make-up effects of Jack Pierce.

You can listen, free of charge, to all of his podcasts on iTunes.

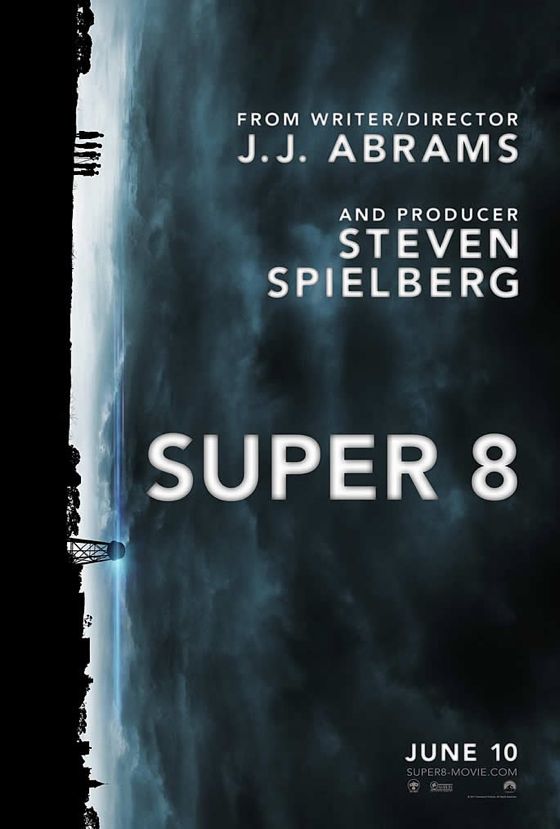

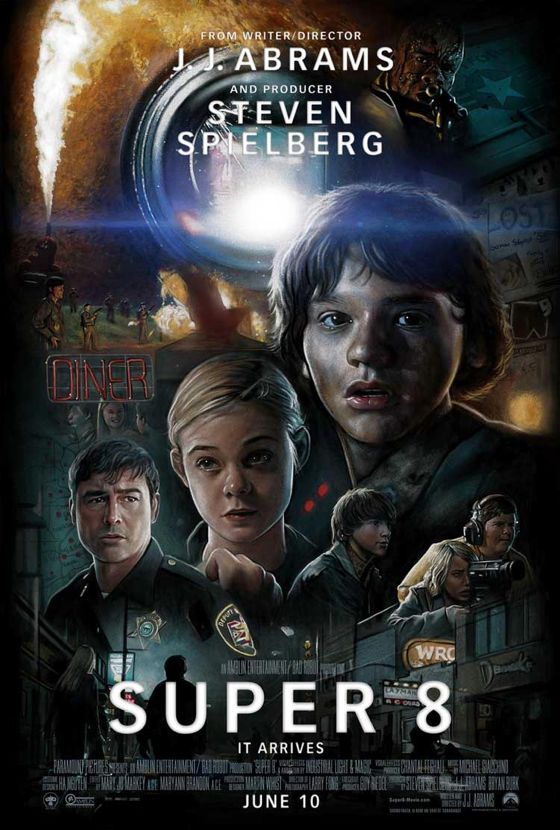

SUPER 8

A few viewings of the movie Super 8 prompt some musings from Paul Zahl (of The Zahl File) on the layers of life and on the difficulty of telling a facade from a foundation:

BACK TO FRONT IN SUPER 8

There are two stories within the movie Super 8. Which is the “front story” and which is the “back”?

There are two different realities depicted in Super 8. Which is true and which is false? Or rather, which is really real?

The two stories of Super 8 are the story of childhood, on the one hand, and of adulthood, on the other.

Joe is grieving the death of his mother, Charles wants urgently, to the exclusion of all else, to finish his movie, Cary loves to blow things up and burn things down, and Alice wants to be able to love her father. The children see nothing else, hear nothing else, and can talk of nothing else. The children are immediate with their feelings: there is no monitor governing their emotions. Moreover, the children find out, long before anyone else does, what's really going on.

The adults, on the other hand, are trying to control everything. The USAF is trying to control the world. Joe's Dad is “scrambling” — the current word — to control the panic of the town. The merchants of Lillian, Ohio are calling their insurance companies; meeting fruitlessly and interminably to discuss the problem, and with all the wrong information; and blaming “bears” or the Soviets. No adult has the slightest idea what is going on, except the local science teacher, who understands it from the inside out.

The children, in other words, are right with the truth, from start to finish. Instinctively, because of their ungoverned feelings — not a bad thing in this movie — they are never wrong, about any aspect of their lives. I believe this is true in life. “A little child shall lead them.” “Unless you become as a little child, you shall in no wise enter the kingdom of heaven.”

The two stories in Super 8 reflect the two realities of Super 8. The children see everything as it is, or you could almost say, only as it is. The adults, so full of worry and fret, so completely engrossed by conflicting supposed obligations and responsibilities, see nothing as it is. The cost to the adults is the near destruction of their lives and town. The gift to them from the children is knowledge, understanding, and reconciliation.

Super 8 is also monistic. It is a monistic work of popular art. By this I mean that it portrays love and compassion — sounds like a cliché, doesn't it? — as universal to all creatures, including alien monsters. The playing field of love is level.

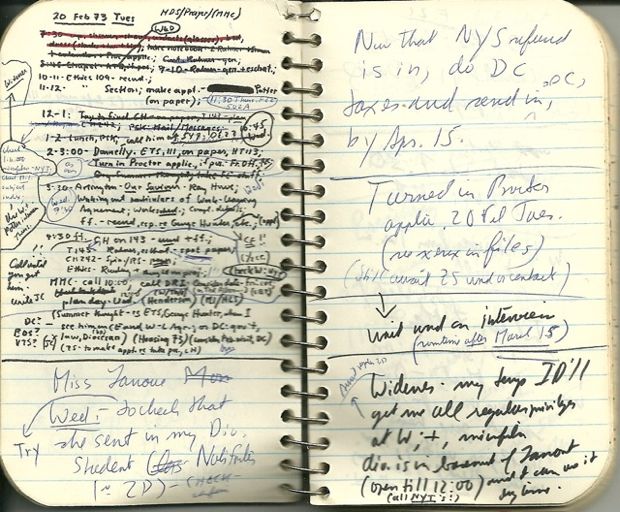

Recently I came across ten little notebooks, notebooks for a person's breast pocket, which I used for my to-do lists during the Winter and Spring of 1972-1973. I was a recent college graduate and quite confused, about absolutely everything. A lot was going on, and just barely underneath the surface. It mainly concerned girls, and sex; not to mention who did I wish to be and become. I was striking out on almost every front, though there were a few shafts of light oddly breaking through. But those notebooks, goddammit!

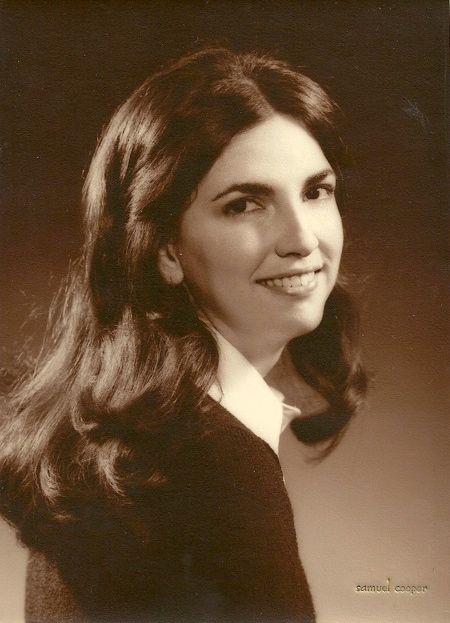

I read them again. They are lists and lists of “urgent” things to do: letters of recommendation to get, applications to complete, courses to take, contacts to make, professions to pursue, taxes to file. Someone named “Mrs. Watson”, the identity of whom I now have no idea but who was probably the administrative assistant to some academic dean, gets innumerable mentions. Yet the only thing I was really thinking about, I mean really, was the person who would later become my wife [below, in a picture from the time]; and how she fit in with some possible other person, and so on.

What I am saying is that my little notebooks carry a “front story”, i.e., “process”, “Mrs. Watson”, and getting into some program or school; and they carry a “back story”, i.e., the core relationship of my future life.

But which was really “back” and which was “front”? It was the opposite of what I thought at the time. The career story was the back story, tho' I conceived it to be the front. The Love Story was the front story, tho' I thought it was the back.

This is a lesson for me from life. If only I could go back to 1973 and live the right emphasis. Just like in Super 8, what you think is the back story is really the only story. [Below, Paul in the Seventies:]

Each of the four times (so far) that I have seen Super 8, I have come home from the theater and dug out my old issues of Famous Monsters. Like the Aga Khan, they are worth their weight in gold. I even found a second issue that had been autographed by Forrest J. Ackerman on the Sacred Day that Lloyd Fonvielle, Bill Bowman, and I were invited to lunch with him.

That's reality. That's the front story. If I could only go back to the future.

IT'S ALIVE!!!!

Paul Zahl and Bill Bowman, robbing tombs in New Orleans last week.

When these guys were teenagers, and I was, too, we used to make 8mm monster movies together. Time has played havoc with us in many ways, but we remain utterly untouched by maturity.

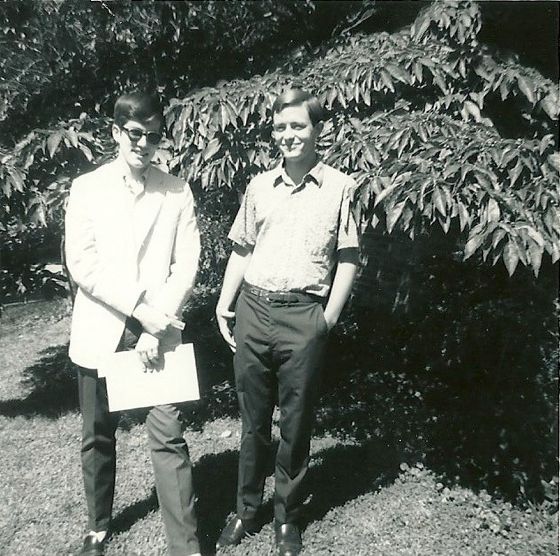

NOTABLE FILM NERDS OF 1966

Paul Zahl, on the left, and myself — possibly just after completing principal photography on The Fruit At the Bottom Of the Bowl, our unauthorized 8mm adaptation of the Ray Bradbury short story. Paul played a debonair seducer who gets his just desserts, even as the wronged husband who delivers the revenge is plunged into madness. I directed and had a bit part as a police detective. We always thought it was important to choose film subjects drawn from our own life experiences.

DRONES

The unmanned drones being used against targets in Pakistan today are controlled from Creech Air Force Base in Nevada (above), about fifty miles from Nellis Air Force Base — just north of Las Vegas, where I live. This is very surreal, but is it also immoral? Paul Zahl offers some thoughts on the subject:

IS ANYBODY OUT THERE?

a now almost canonized but then extremely unpopular speech in the House

of Lords, Bell challenged the Government on its bombing policy. In the play Soldiers Hochhuth imagines a personal meeting between Winston Churchill and Bishop Bell, in which they debate the morality of bombing from the air, especially when there is the possibility, even the probability, of civilian deaths.

Churchill believed that the bombing of civilian centers was essential to the Allies' winning the war. Bell believed it was a war crime.

Here are a few lines that the playwright puts in the mouth of Bishop Bell. They are mostly lifted from Bell's speeches and writings, or deduced from them:

Stage Direction:

“BELL, by his quiet strength, has released something akin to shame in CHURCHILL. This cannot be indicated logically, only portrayed illogically. The feeling does not last. The PRIME MINISTER is discomposed for a moment by the knowledge that someone is stronger than he is.”

Bell is a saint, in memory, of the Church of England. Then, he was a

pariah. Dresden was still bombed. The Atom Bomb was dropped, twice. [Below, the aftermath of Dresden:]

about combatants who cannot see, for a distance not of 30,000 feet,

but of 10,000 miles, the enemy, let alone the enemy's family, who are

burned in an instant to a cinder?

What would the hero of Hochhuth's Soldiers think about what we are doing today?

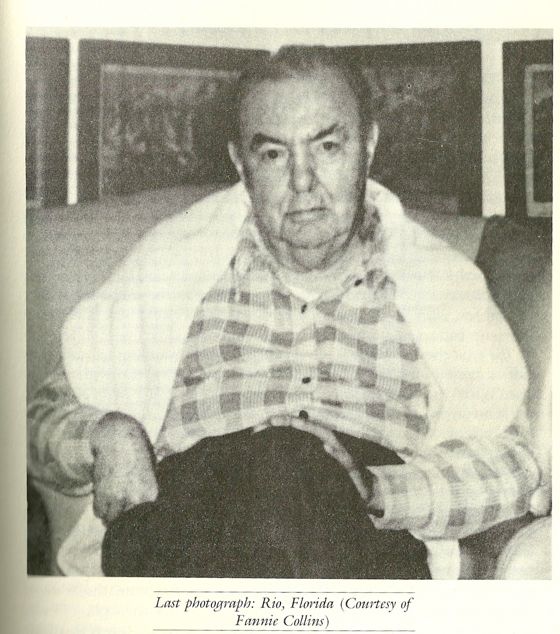

CONDO COZZENS

Above is the last picture taken of James Gould Cozzens, in the Florida

condo where he lived with his wife from 1973 until his death in 1978.

As readers of Paul Zahl's posts on this site (in The Zahl File) will know, Cozzens had been a major literary celebrity in the 1950s and a

best-selling author, but some unpleasant (and inaccurate) reports of

his personal prejudices along with shifting tastes in literature left

him all but forgotten at the end. He's probably best known today as

the author of By Love Possessed, which was made into a Hollywood film.

Below is a photograph of the condo as it stands today, taken a few days

ago — the date-stamp is wrong:

[Photo © 2010 Don Whalen]

It's at Beacon 21, Rio (Jensen Beach), Florida. When Cozzens moved there

permanently from New England, he sold his large library and basically

stopped writing, except in his diary. He puttered in a small garden

attached to his condo and watched TV.

He was especially fond of The Mary Tyler Moore Show and also got into

the Watergate hearings.

The New York Times was on strike when Cozzens died, so he never got a proper

obituary there. The obituary in his local newspaper was terse, and

described him this way — “He was a distinguished writer and author,

and was an Army Aviation

Corps veteran of World War II. He was of the Episcopal faith.”

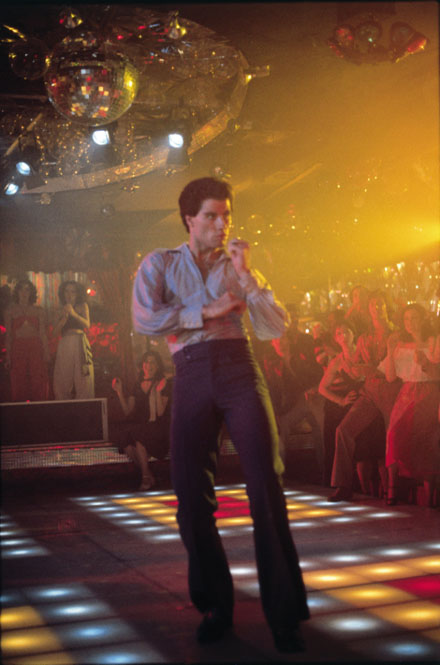

The times for local movies were printed directly beneath the obituary

— playing that week were Saturday Night Fever, Star Wars and Jaws

2.

Paul Zahl, on whose research the above is based, and whose friend Don

Whalen took the contemporary photo of the condo complex, says that

Cozzens was actually more of an Episcopalian agnostic, verging on

atheist. Paul also notes the echo of Jack Kerouac's last isolated days

in Florida — Kerouac watched a lot of TV, too. He was fond of The

Beverly Hillbillies.

American writers often come to strange ends — but then, so do most of us.

[Go here to see a piece Paul wrote about Cozzens's earlier home in

Lambertville, New Jersey — a long way from Jensen Beach.]