Thou enlightenest wonderfully from the everlasting hills.

— Psalms 76:4

Another superb dossier for The Zahl File — Paul Zahl on two extraordinary movie sets from two oddly related films:

Autumn on the Hill

by Paul F. (“Maleva”) Zahl

“It is always the end of autumn on the hill, the spirit of a year has passed through. In the fall school begins, you feel very young, the trees teach a lean lesson about paths in life. The atmosphere of the hill is heavy, pungent; leaves are burning somewhere, even though there are Martians.”

— Dennis Saleh, Science Fiction Gold (1979)

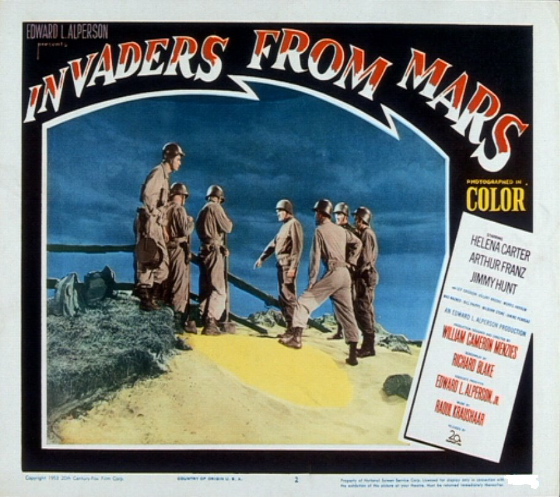

The hill referred to is from Invaders from Mars,

a dreamlike film from 1953 that concerns aliens who take over the minds

of a little boy's parents. The intruding saucer is buried beneath a

hill behind the family house. At the top of the hill there is a hidden

opening into which humans are dragged down, like in quicksand, to be

implanted with alien control devices. Invaders from Mars is

famous for many things, the chief of which is the set design, much of

it created to look as if seen from a child's point of view. The autumn

hill is the big prop, with its picket fence, and no one who saw this

movie as a child will ever forget that hill. Invaders from Mars was directed by William Cameron Menzies, who had also directed Things to Come in 1934.

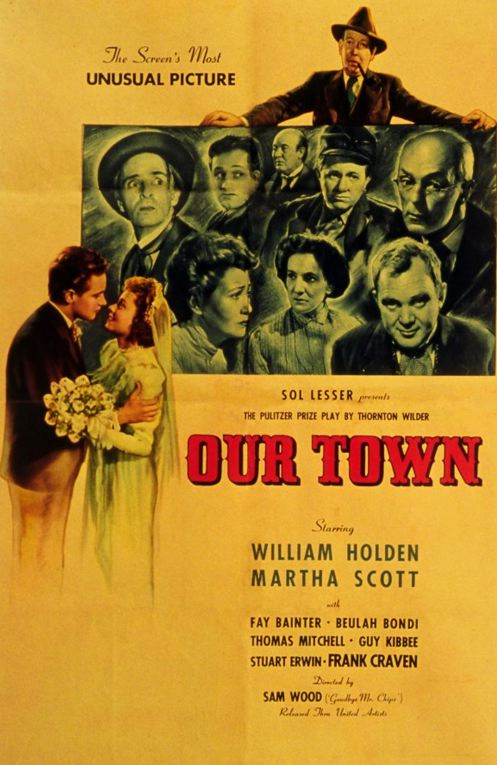

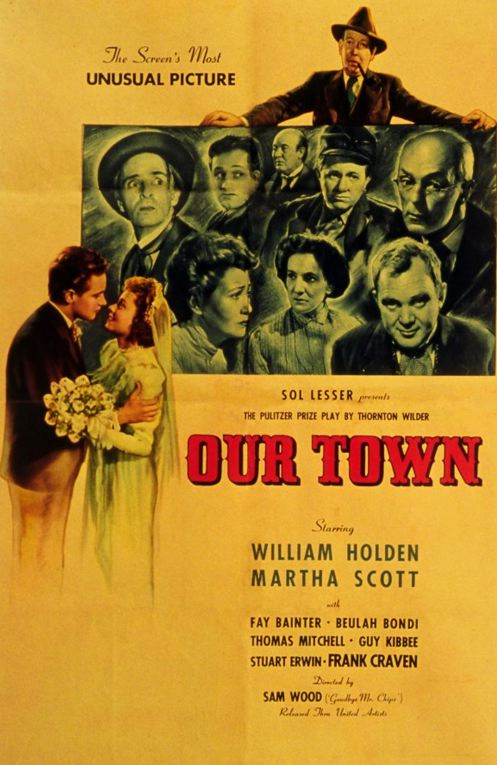

There is another hill designed by Menzies. He was

production designer for the Hollywood version of Thornton Wilder's play Our Town and praised for his beautiful set for that drama of life and

love and death in Grovers Corners, New Hampshire. The keystone of

Menzies' design for the film version of Our Town (1940) is another autumn hill,

with another picket fence. The movie begins with the hill, as the

Stage Manager emerges from it, gently stooping to pick up broken pieces

of its picket fence; and the movie ends with it. The concluding

section takes place almost entirely on the hill, which is the autumn

place of the dead, the site of the town cemetery, where most of the

characters now stand, dead, in quiet distance from their earthly lives.

This cinematic version of Our Town is very good. It is

filmed intimately, with long conversations between leading characters framed in close shots, almost like early television, although the

photographer was Bert Glennon, who also worked with John Ford. The

acting is excellent. The movie is never self-important. It exists to

capture the feel and thought of the Wilder original. Jack Kerouac, by

the way, who praised few of his literary contemporaries, wrote, “Our

Town by Thornton Wilder is vastly enlightened, the dream ended,

Scrooge looking back.”

Of all the images of this subdued and beautiful

meditation on film concerning beginnings and endings, the autumn hill

of William Cameron Menzies sticks in my mind. The place it occupies is

not so far from the autumn hill in the little, later movie, the

claustropobic and domestic picture of alien invasion.

The two hills are the same. They exhibit the end

of human identities and human striving. One malevolent, one benign (if

somewhat indifferent), they both represent the negation of human

existence in the presence of something bigger and larger. The people

on Wilder's hill have lost their lives and become indifferent to what

they (thought they) had. “. . . all those terribly important things kind

of grow pale around here. And what's left when memory's gone, and your

identity, Mrs. Smith?”

This is a meditation on death, the caesura to end all human

intentions. While he was composing his play, in 1934, Wilder described

it in a letter as “A theologico-metaphysico-transcription from the Purgatorio with panels of American rural genre-stuff.” (He wrote most of Our Town, by the way, far from the 'Grovers

Corners' of America. He wrote it in the Zurich suburb of Ruschlikon,

almost next door to where my own sons attended middle school in the

1990s.)

Menzies' other autumn hill, constructed 13 years

later on a 20th Century Fox set, is parallel. It sure looks the same!

It, too, hides the end of human striving, this time because of hostile

aliens, who make no distinctions between women and men, children and

their parents, nurses and soldiers, as they destroy their identities

and take them over. When I first saw Our Town the movie, I felt instinctively the chill of the hill. It was unsurprising to read, years later, in the correspondence between Sol Lesser, the producer of Our Town,

and Thornton Wilder, the author of the source, that William Cameron

Menzies was being praised for his achievement in the design.

Two hills, one benign, if indifferent, and one

malignant, each exhibiting negation. Positively, I would like to say

that the autumn hill of Our Town represents a funerary and

profound transcendence, the end of engagement with life on its own

repetitious terms, in favor of the very biggest picture, which is

forced on us human beings, whether we like it or not, by the fact of

physical death, and sometimes death-in-life . . . even though . . . there

are Martians.

Editor's Note: I found the above frame grab from Invaders From Mars on the DVD Savant site, which has a long and interesting review of the film, including this observation on the hill set:

The Sand Pit Hill Set

Menzies appears to have put the majority of his resources into one

very large, very special set, the hill leading to the Sand Pit behind

David's house. It is one of the most remarkable sets ever made, for a

number of reasons. A slightly curved path winds up the hill between

some leafless black tree trunks, followed by a broad plank fence. Atop the hill, the blackened fence dips out of sight into the largely

unseen Sand Pit beyond.

The hill is 'deceptively artificial.' On first impression it reminds of

the bridge in the 1919 Cabinet of Caligari, the bridge over which

Cesare the Somnambulist kidnaps his female victim. The Invaders hill

appears to be a similarly flat-perspective, diorama-like design. In

static shots it resembles a painted backdrop. But when an actor walks

up the path, all sense of perspective goes haywire. The hill is like a

2-dimensional painting, but 3-dimensional people defy visual logic and

diminish as they walk 'into' it. It's a 'reverse forced-perspective'

optical illusion. George MacLean seems to get smaller than he should as

he reaches the top of the hill, and it takes a lot of steps to get him

there. But the trees at the rear of the set don't give the right

'perspective clues,' so it almost looks as if George MacLean is

shrinking as he walks. It is a subtle effect that is more easily

perceived on a large screen.

Click here for the full review.