There

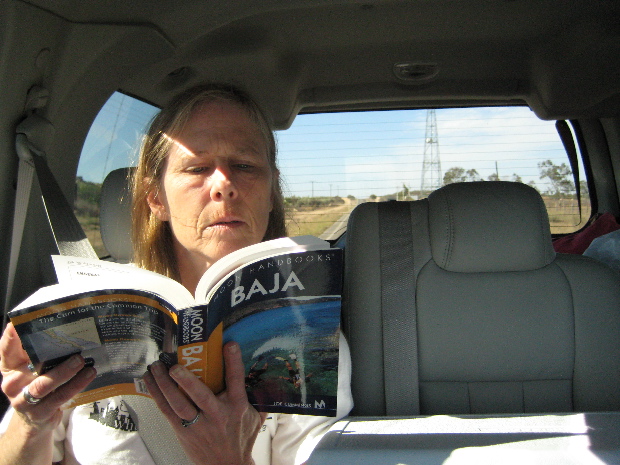

is just no way to describe the coast and the islands of the Mar de

Cortés. Parts of it remind you of stretches along the coast of Alta

California as it must have been in frontier times. Most parts of

it seem like a landscape from another planet, or like our own earth

reduced to its purest elements — sea, land, no frills.

Every mile of Mexico 1 that takes you within sight of the Mar de Cortés is beautiful and inspiring.

Driving east from San Ignacio we hit the Mar de Cortés just north of

Santa Rosalía. Then we drove south in a state of enchantment to

Mulegé, a town built next to a palm-lined estuary, and stopped for

lunch at Dony's taquería,

where we had some fine shrimp and carne asada tacos at a sidewalk

counter. Then we followed the road down the coast to Loreto,

where we spent the night.

Loreto is rumored to be the “next cool place” in Baja California, which

means that developers are building fancy condo compounds near it.

The town itself is pleasant enough, though a bit touristy. It's a

famous place from which to set out on the Mar de Cortés for fishing,

and we found that American fishermen tended to be the most

objectionable tourists in Baja California — mostly white, middle-aged

men with loud voices pretending to be Ernest Hemingway and behaving as

though Mexico was a country populated entirely by domestic

servants. (We eventually became fishermen ourselves, however, and met some

very nice pescadores among the blowhards.)

The La Pinta inn we stayed at in Loreto was the shabbiest one we

encountered on our trip but it had a big pool right next to the ocean

with an island in the middle of it that thrilled Harry and Nora.

Nora also had her first piñada here, a pineapple smoothie. She became an afficionada

of the concoction and had them everywhere, rating their

qualities. The ones with a cherry and a pineapple slice included

always rated highest, especially if they were served in a large

frosted-glass goblet.

Lee had her first fish ceviche

at the restaurant at the inn, which became an obsession of hers for the

rest of the trip. All of it was good, but the best was a ceviche made from a trigger fish I caught myself . . . but that's a tale for another time.

On the Mar de Cortés, sunsets like the one above, at Loreto, which look unreal at first, quickly begin to seem routine — I guess because they are.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]