[Note — this post contains plot spoilers and shouldn’t be read if you haven’t already seen Leave Her To Heaven.]

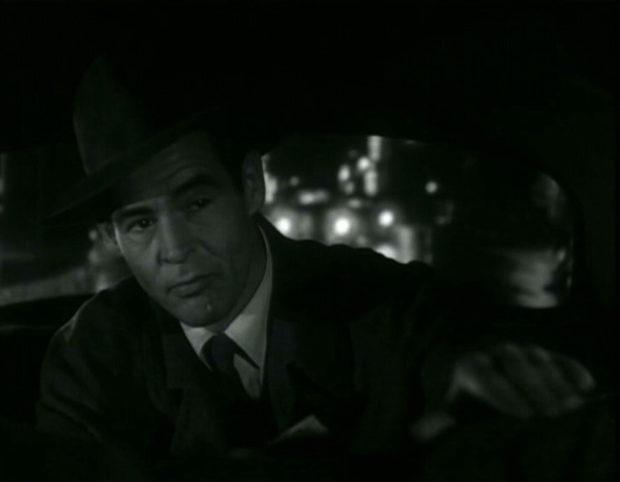

Leave Her To Heaven is one of the strangest films ever made in studio-era Hollywood. The tension between its text and its subtext is so violent that it can induce mild dizziness. It’s sometimes called, unhelpfully I think, a film noir. It’s certainly a dark film, despite its gorgeous Technicolor photography, and it deals with some of the same cultural neuroses that inform the noir tradition, but it comes at them from a different perspective — a female perspective.

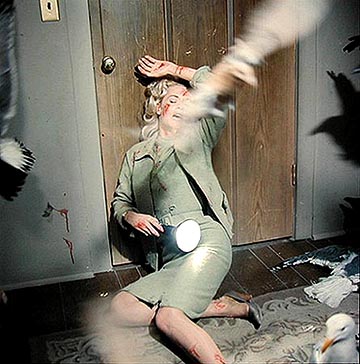

At the heart of the film is Ellen, played by Gene Tierney — a

beautiful, narcissistic psychopath. We’re told early on that

Ellen wrecked her parents’ marriage by her obsessively close

relationship with her father. The minute we hear this

extraordinary bit of information our perceptions should be alerted that things

aren’t always going to be what they seem in this film — though I

imagine that it’s mostly women who pick up on it, and perhaps only

subconsciously.

Think about it. A grown man allows his marriage to be ruined by his obsessively close

relationship with his daughter — and the child is blamed. This

strikes me as a kind of emotional code, alluding to the phenomenon of blaming

women for the psychic and moral failings of men.

Ellen will go on in the course of the film to do horrible things — she

will murder a crippled boy, her husband’s brother, she will induce

the miscarriage of her own unborn child and she will try to frame her

innocent cousin for murder. She becomes a monster and no rational

consideration can induce us to sympathize with her — but we do.

We do because of the coded text embedded in the overt one.

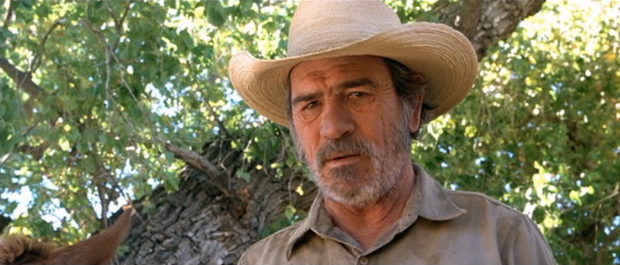

In the film, Ellen falls in love with and marries Dick, apparently

because he reminds her of her father. Cornell Wilde is

brilliantly cast in the role. He looks like a hunk but is a kind

of black hole on screen, with a blank face and eyes that express little

more than hurt and bewilderment. He’s further un-manned in the

narrative, which makes him a fumbler, insecure around Ellen, easily led by

her and only too happy to retreat to the female company of her mother

and cousin, “good” women but good in a bland, smug way.

Dick has a crippled younger brother who comes to live with the

newlyweds — sleeping in the room next to theirs behind a wall so thin

that he can talk to them through it without raising his voice.

Dick doesn’t seem to comprehend why this situation makes Ellen

uncomfortable. When the brother is finally moved out to a guest

house Dick secretly invites Ellen’s mother and cousin to come visit,

another intrusion on their intimacy, and once again can’t understand why this disturbs Ellen. He whines out his reasoning — “I thought you’d be pleased!” — without the slightest apparent awareness of Ellen’s point of view, much less her right to be consulted on such things.

Ellen over-reacts, of course — drastically. She lets the brother

die in a swimming accident. But part of us understands why she

does it. All the people around her are so drippy, so dull and, in

the case of the men, so weak, that part of us wants her to kill them

all.

This is how the deep tension of the film is created — by giving Ellen

real grievances, maddening and suffocating, while at the same time

giving her responses that we can judge as thoroughly

reprehensible. Men are allowed to righteously condemn a woman who

sees through male weakness, women are allowed a vicarious revenge

against those same weak men.

The film starts on a train and climaxes in a courtroom, but in between

it plays out in a series of glamorous vacation homes, shot in wild,

almost lurid color. The whole film is like a paean to the

well-decorated second home — a glossy magazine-spread celebration of

bourgeois comfort and excess. But Ellen makes us feel the

oppression of those homes — they are for her what the urban labyrinth

is to the lost souls of film noir, and they’re lit with the same expressionistic exaggeration.

Gene Tierney was an actress of limited range but she turns up in some

of the great films of Hollywood’s golden age, radiant and unforgettable —

this film, Laura, Heaven Can Wait and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir.

She had a unique quality on screen, part aristocratic, part down to

earth, always suggesting a secret that will never be revealed.

That quality, and especially it’s sense of impenetrable mystery, is

what allows us here to project onto her our unconscious approval of her

wickedness.

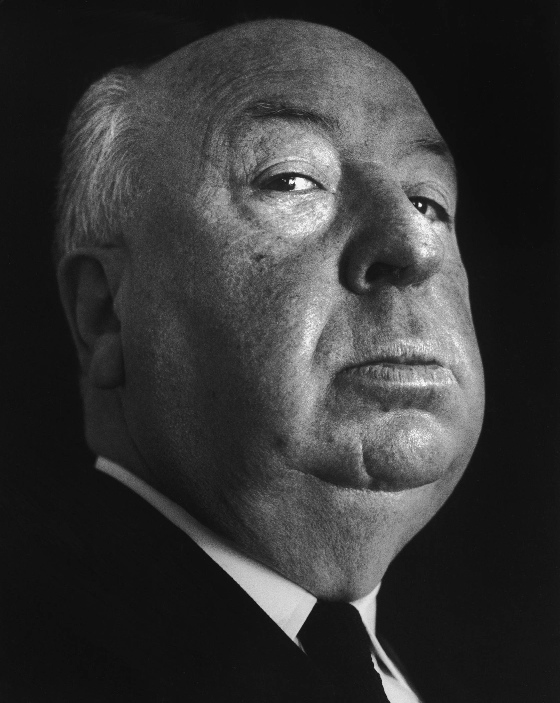

While not a true film noir the movie fits nicely into a category that might be called domestic noir — along with Shadow Of A Doubt and Double Indemnity,

both made around the same time. In these films, the nightmare of

moral chaos doesn’t play out on dark city streets but in middle-class

homes . . . yet the existential dread invoked is almost exactly the

same.