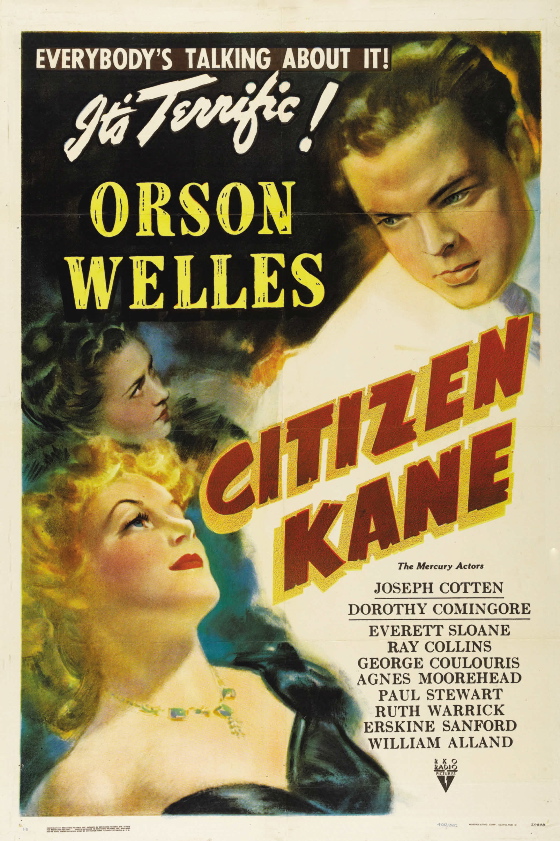

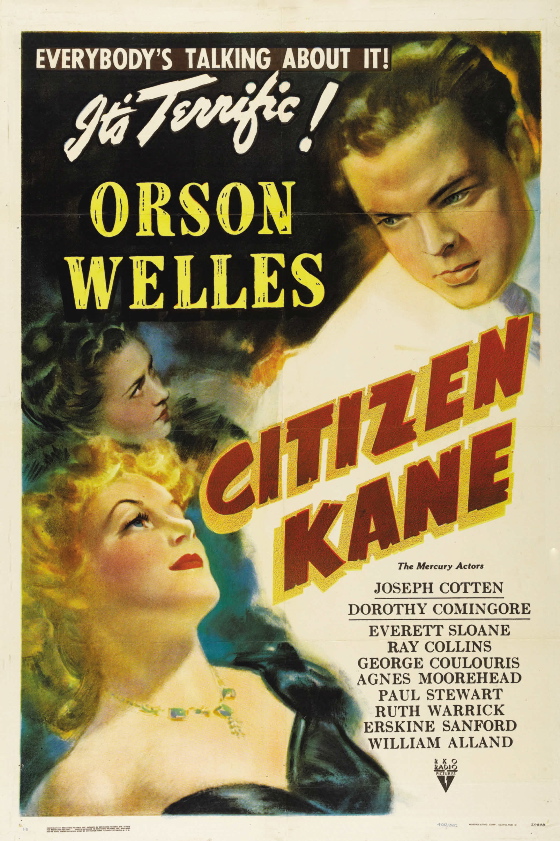

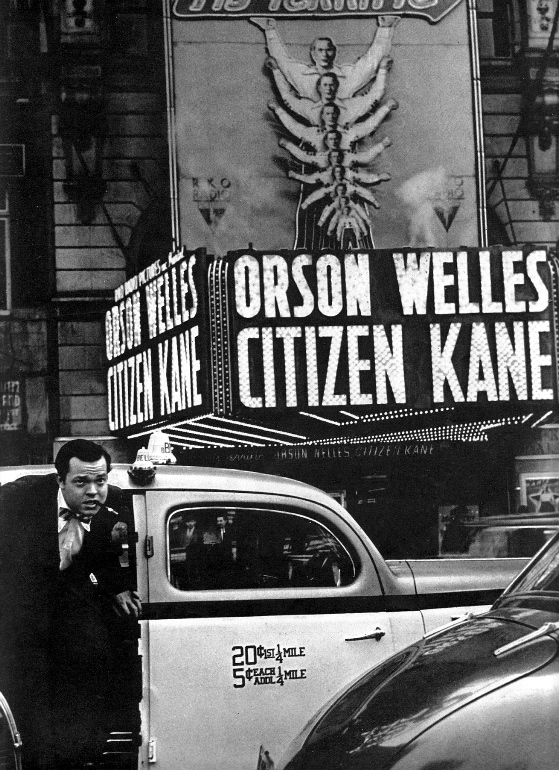

Citizen Kane

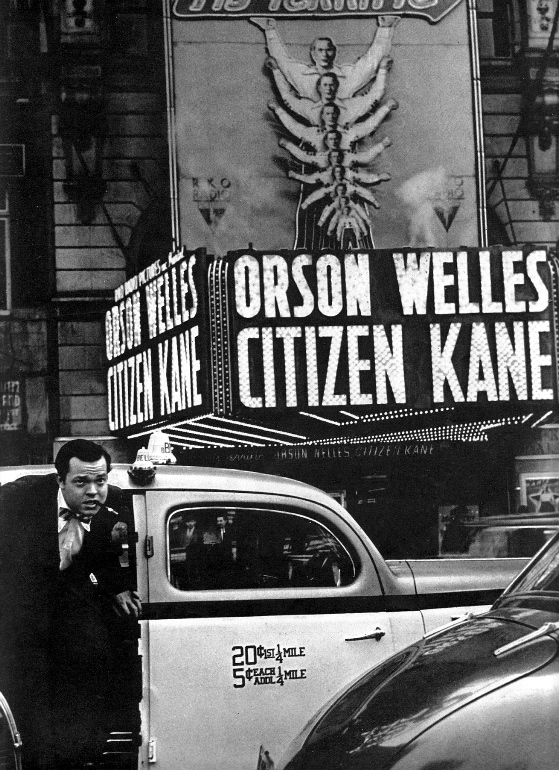

is a hard film to “see”. It's so alive with invention, so dense

with magical images (and camera tricks) that it's difficult to process

them in detail. The film also has a relentless narrative drive,

aided by visual, musical and other sound transitions of exceptional

virtuosity which keep one in a perpetual state of anticipation.

The rap on the film has always been that all this razzle-dazzle

distracts one from the fact that Kane is hollow at its center — an

exercise in sensation rather than substance. This is a complaint

that was often made about Welles' stage productions — that they were

thrilling while you were watching them but evaporated instantly from

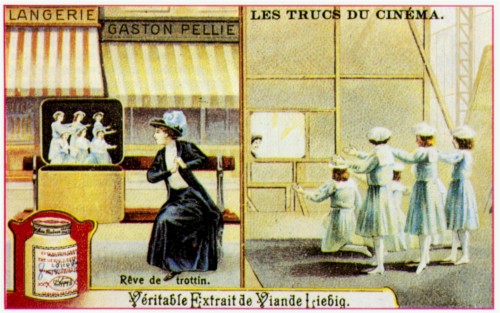

the mind afterward. Pauline Kael saw Kane

as a magic show — and a magic show is another kind of theatrical

experience that lives only in the moment, that has no artistic echo.

I myself disagree with this view of Kane.

There is a hollowness at the center of the film but it's the hollowness

of Kane himself, of the character — not the actor who plays him or the

film's director (who of course are one and the same man.) The

sharp dialogue and knowing wit of the film, the insistent technical

bravura of the filmmaking, tend to disguise the fact that Kane is a grandly sentimental work, a work of great compassion and feeling.

I have no doubt that this sentiment and compassion came from Welles

himself, though he may have been steered into it sidewise by his

screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, who put a lot of Welles into Kane under

the cover of the roman à clef

element that related the character to William Randolph Hearst.

Welles always said that the Rosebud theme was all Mankiewicz's doing,

and that he wasn't terribly fond of it himself. I would argue

that the Rosebud theme, far from being the artificial MacGuffin it's

often dismissed as, even by Welles, is in fact exactly what it seems to

be — the key

to Charles Foster Kane and to the film. This may have been

something Welles could not admit because it struck such a deep nerve in

him.

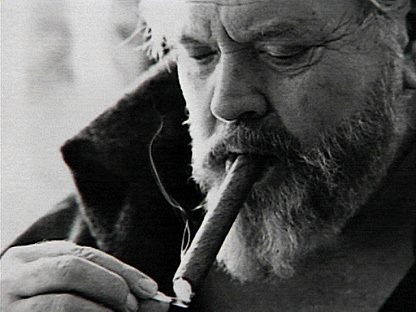

Welles is often treated as a uniquely mysterious character, a mass of

irreconcilable contradictions, but I think this is no more true of

Welles than it is of Kane. Everything about Welles makes perfect

sense if you remember that he lost his mother, an adoring but demanding

woman, to jaundice when he was 9, and that he lost his father, by a

longer process, to alcoholism, which finally killed him when Welles was

15.

Welles cut himself off from his father six months before his death, in

an effort to get him to face his drinking problem, and never forgave

himself for the betrayal, for allowing his father to die alone and

estranged from him — something he could never make up for. It's

not dime-store psychology to see these traumas as the forces which

fueled and warped the unfolding of Welles' genius — they are primal

emotional events. And so with Kane's abandonment by his mother

and father.

The nostalgia for Rosebud, for what it represents, does sum up Kane's

life, and it's not a simplistic analysis. The loss of a parent in

childhood is a wound that never heals — it can be endured but never

overcome. A child always sees the loss of a parent as a rejection

— in the case of Kane, his mother's decision to send him away was on one level a literal rejection, however well-motivated.

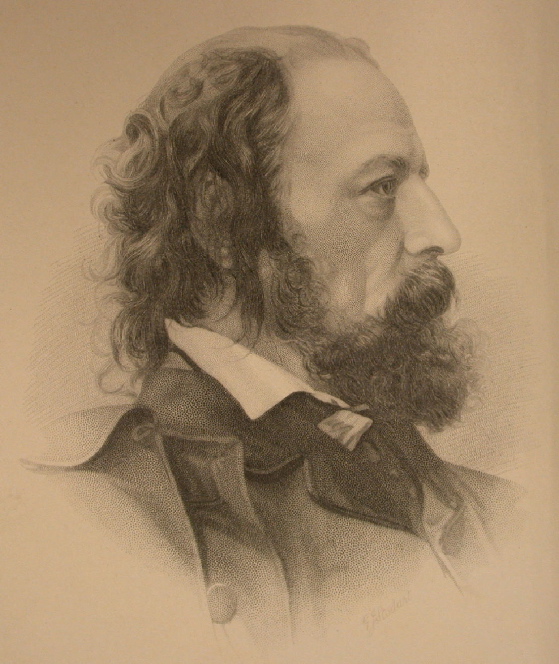

Simon Callow, Welles's most astute biographer, is dismissive of Welles's performance in Kane,

feeling that it never achieves depth, and he feels this way about most

of the performances in the film — with the notable exception of that

by Agnes Morehead as Kane's mother. We don't see her for long but

we sense worlds of grief in her as she sends her son out to the wider

world, where she hopes he'll have a better life.

It is a singular performance in

the film, but I think its singularity makes perfect sense. Kane

has a hole in his heart which robs him of personal substance, makes him

a perpetual performer incapable of real intimacy with anyone. And the

significant others in his life are content to be his audience —

thrilled or appalled by his “act”, excited and inspired, but with no more real

commitment to him than a theater audience has for the lead actor in a

play after the curtain comes down, or after his celebrity fades.

We share their guilt in this, of course — we the audience are also

thrilled and appalled by Kane's act, excited and inspired, amused by his rise and morbidly delighted by

his fall. But Welles won't let it go at that.

The story of Kane is a shadowplay, with one real person at its center

— Agnes Morehead's Mary Kane, who has unwittingly, in an act of misguided

sacrifice, turned her son into a shadow. There are many moments

in the film, especially as Kane ages and begins losing everything, when

Welles lets us (though not the other characters in the film) into his

psychic universe, a place of bewilderment and pain.

Welles is curiously least convincing when he plays Kane at

the age Welles actually was when he made the film — he's like an older

man doing an unconvincing imitation of a younger one. It's as

though Welles doesn't know how to be young — but that works for the

young Kane, a man born to power and wealth, who has to play at being a

regular lad. Yet Welles is utterly convincing as the older Kane

— as though he knew in advance what it would be like to hold the world

in your hands and then see it slip from your grasp. Callow

suggests that the young Welles is preserved in Kane

like a fly in amber but the truth is far stranger — the

older Welles is on display in that film, fully formed (and deformed) by

the vicissitudes of failure and disappointment.

This is uncanny, of course, and in retrospect disturbing — but it

represents a brilliant imaginative leap for the young actor, one he summoned up from the core of his being, and it's very

moving. Welles asks us,

and allows us, to pity Kane, to forgive him — and he gives us good and

sufficient reason to do both.

Rosebud.

The ambiguity, the unknowable quality of Charles Foster Kane is the real MacGuffin

of the film. Rosebud is its heart, hiding in plain sight in the

last scene just as the truth of Kane hides in plain sight throughout the

film.

[Thanks to six martinis and the seventh art for the screen grab of the sled in the snow.]