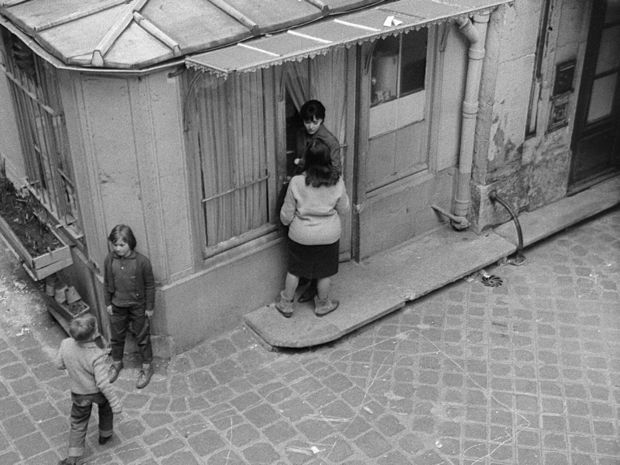

The third tableau, or chapter, of Godard's Vivre Sa Vie is primarily about the cinema. It begins with a transitional scene connecting it to the preceding tableau which showed us the protagonist Nana's working life. She returns home but cannot get the key to her apartment from the concierge, because she owes back rent. We know from the preceding tableau that Nana has lent 2000 francs to a co-worker, who wasn't at work that day.

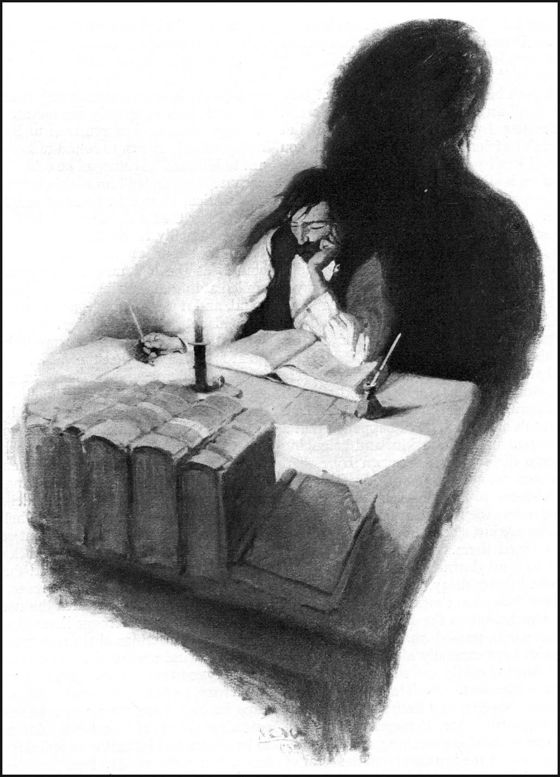

Cast adrift in the city, Nana meets a friend by chance on the street, the guy she was breaking up with in the first tableau, who shows her some pictures of his child, apparently a child he had with Nana. Her only relationship with the child now seems to be through these photographs, through images.

Nana refuses an offer of dinner from her ex because she wants to go to the movies. She goes to see Carl Dreyer's silent film La Passion de Jeanne Arc at the Jeanne d'Arc theater. She's sitting with a date, who has his arm around her, but she is utterly absorbed in the film.

Godard shows us a relatively long passage from the film, cut into his own film — in other words we don't see this passage as images playing on the movie theater screen, which is never shown in the shots inside the theater. Thus, when Godard cuts from Dreyer's extreme close-ups of the suffering Joan about to meet her death to a close-up of Nana reacting emotionally to the images, a kind of equivalence is suggested, on two levels.

Nana is identifying with the character Joan . . . but Anna Karina, playing Nana, is also mirroring or doubling the actress Falconetti, playing Joan. Karina is entering the history of film as an image.

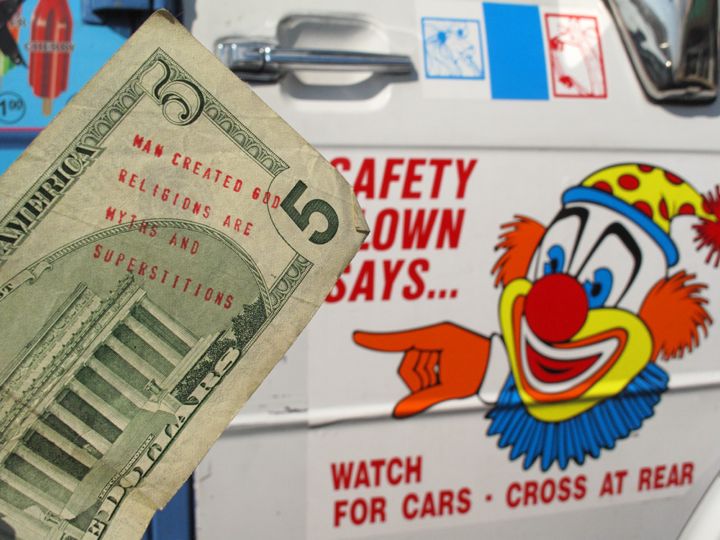

After the film, Nana ditches her date, whom she's apparently just hustled for the admission price to the movie, and goes to meet another man at a café. We've seen Nana “servicing” a male customer at the record shop — now we've seen her trading a little groping for a movie ticket. In the first tableau, her boyfriend accuses her of breaking up with him because he doesn't have enough money — and she doesn't exactly deny it. Godard is establishing the idea of her persona, especially her sexual persona, as a marketable commodity.

Nana and the new guy she meets sit beside each other at the café bar, like Nana and her soon-to-be ex in the first tableau, but they face each other, and we can see their faces. The camera tracks back and forth between them nervously, mostly keeping them in a two-shot but one that's constantly reconfigured.

This nervous, apparently unmotivated tracking makes us conscious of the camera, even as Nana and the man discuss photographs he's going to take of her to help her break into the movies, which is her dream.

The ironies grow elaborate. Godard has already put Karina into the movies, into this movie among others, and suggested an equivalence between her image and some of the most iconic images in all of cinema — but the character Nana is somewhere far behind the actor playing her.

Curiously, this dissonance doesn't disrupt either our sympathy for the character or our delight in Godard's abstract aesthetic gambits. The two levels of meaning play against each other in a logical and beautiful way, like two counterpointed lines in a Bach fugue.

Next:

Previously: