There is no place for Westerns in modern corporate culture but that doesn’t mean that the form is no longer alive in the American and in the world’s imagination. Any Hollywood studio executive will tell you, as though reciting the Nicene Creed, that audiences don’t want Westerns, and publishers will say the same of Western fiction. Both are craven lies.

When a traditional Western manages to slip through the cracks in Hollywood, it invariably meets with success. Dances With Wolves, Unforgiven, Tombstone, Open Range and the Coen brothers’ True Grit all turned a profit, and a few of them, True Grit conspicuously, made a very great deal of money. Non-traditional, cynical Westerns, the sort of Westerns that appeal to the collapsed males who run Hollywood, invariably flop. These dreadful men make their case from the latter type of Western, and ignore or explain away the former type. It may be that they don’t even know the difference between them.

Larry McMurtry’s great Western novel Lonesome Dove was a huge bestseller, and was made into a tremendously successful television mini-series. McMurtry’s other Western novels have sold well, too. Publishers find ways of believing that these facts don’t count. Westerns remain anathema in the world of fiction.

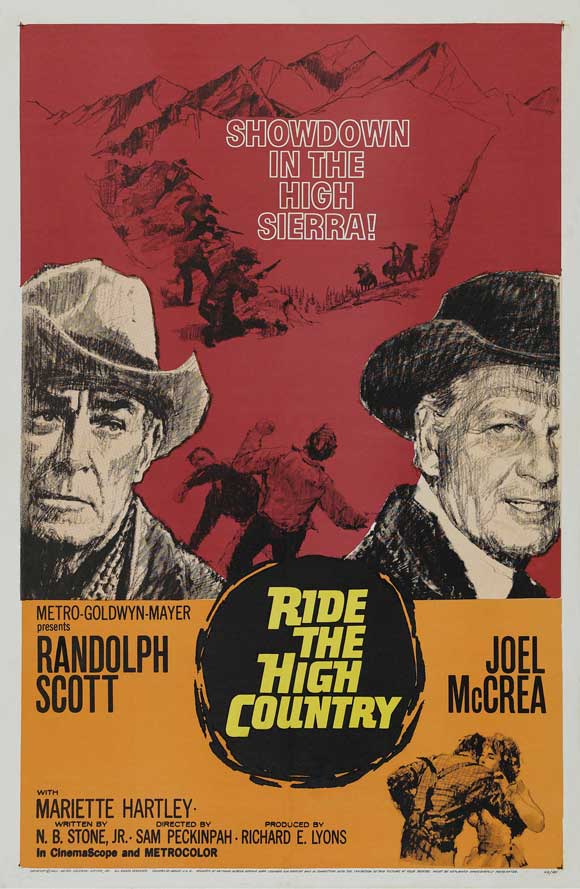

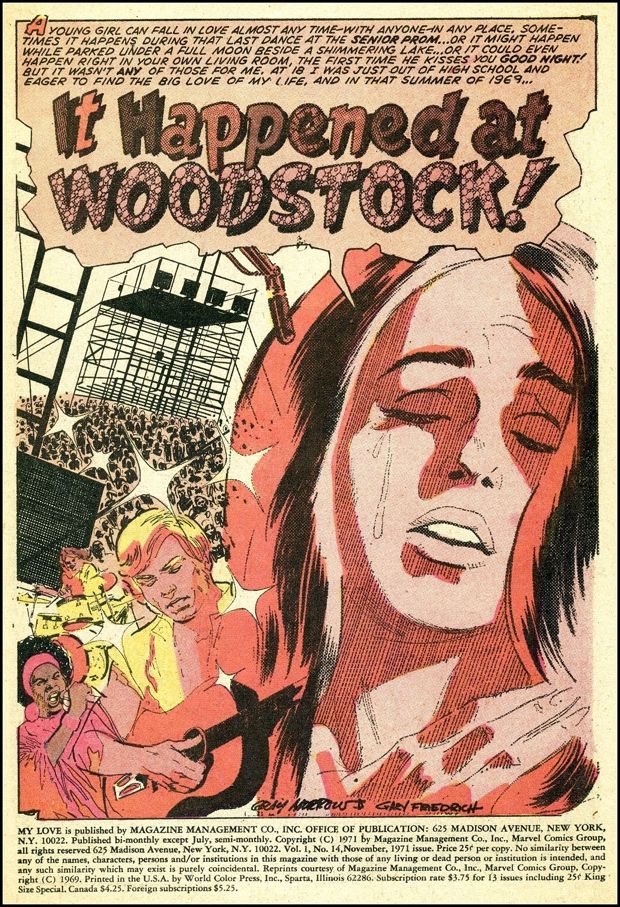

Part of the problem, it must be admitted, lies with the creators of Westerns. Many of them did not notice how the Western was evolving in Hollywood, just before it lost its credibility with the studios. In the Sixties and early Seventies, the Western was starting to incorporate the female sensibility into its generic concerns. This could be seen most clearly in Charles Portis’s novel True Grit, made into a somewhat compromised film by Henry Hathaway, but also in the early works of Sam Peckinpah, like Ride the High Country and The Ballad Of Cable Hogue. Peckinpah would eventually self-destruct as an artist and a man, indulging in his personal nihilism and misogyny to the detriment of the Western genre, taking it down an apparent dead-end street and leaving it there for dead.

Curiously, it was around this same time that McMurtry, long before he wrote Lonesome Dove, recognized where the Western needed to go—into the female experience, into the female psyche. This, he saw, was the great undiscovered country of the genre, the path to a renaissance of the form. In discussing the future of regional Texas literature he wrote, in 1968, “Literature has coped fairly well with the physical circumstances of life in Texas, but our emotional experience remains largely unexplored, and therein lie the dramas, poems, and novels. An ideal place to start, it seems to me, is with the relations of the sexes, a subject from which the eyes of Texas have remained too long averted.”

McMurtry, writing here in a book of essays about Texas called In A Narrow Grave, was not talking about the Western itself as a genre, but he might as well have been. And he was certainly not talking about making Western literature responsible and inclusive, incorporating female experience out of sociological or feminist obligation. Elsewhere in the book he bemoans the idea of movie Westerns becoming “responsible”, obliged to convey any particular political or sociological messages. This was part of what killed the Western in the Sixties—the idea that the national myth had to reflect modern guilt over things like Vietnam and civil rights, had to own up to the fact that America was always rotten, its heroes always fraudulent.

As if Westerns had ever tried to sell their visions as historical fact! Westerns have always been wisdom tales, not history tales. They deal, as writer Ray Sawhill has observed, with issues of shame and honor, as opposed to modern film stories (and non-traditional Westerns) which deal with issues of guilt and therapy.

It’s a crucial distinction. Shame incorporates a perception of personal failing, honor a sense of self-worth restored through action, action that can just as easily involve sacrifice and forgiveness as gun play. Guilt, on the other hand, can be seen as something imposed unfairly from without, by parents or priests or society, curable by therapy, which can be bought and consumed passively.

Stories based on guilt and therapy are not really stories—they’re self-help case studies, often entirely delusional.

But imagine a new frontier for the Western, a territory in which it might be possible to deal with the relations of the sexes in terms of shame and honor, without political correctness, aiming only to entertain and inspire, not gratify and instruct.

The Western will go there some day, and when it does we will forget the time when it seemed to have vanished into thin air before our longing eyes.