It's absurd to see the current economic crisis as a failure of market capitalism, as some sort of vindication of the writings of Karl Marx — though this is a theme of much commentary on the subject from the radical (and not so radical) left. The financial shenanigans of the Wall Street hustlers in recent years resembled no “market” in the history of human civilization. Markets are cruel at times, unfair at times, manipulable to a degree, but essentially, in the long term, logical.

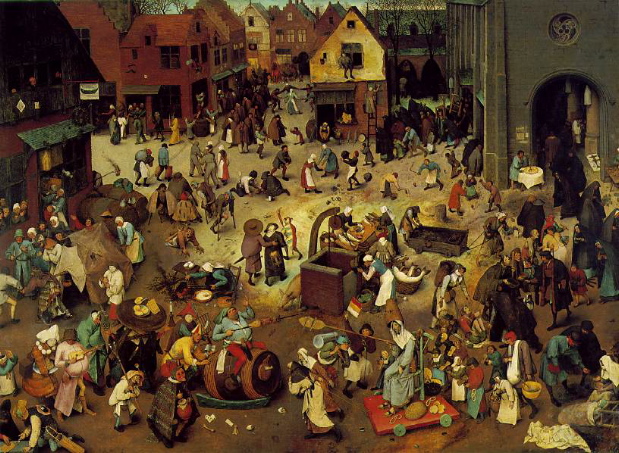

In the Middle Ages, if you sold cow-dung pies at the fair by telling people they were mince pies, one of several things would certainly have happened to you. Most probably you would have been taken out back of the cathedral and beaten to a pulp. You might have been fined or imprisoned by the local authorities for your temerity and mendacity. At the very least you would have forever ended your ability to sell pies at any fair within the reach of gossip emanating from the fair where you got busted — and that reach would have been very far, even in the days before the rise of sophisticated communication technologies.

In short, the market would have disciplined you for your fraud.

There has been no such market discipline at work on Wall Street in recent years. People sold cow-dung pies as mince pies with no thought that they would ever have to pay a price for getting caught. They knew that the government, through corrupted legislators and regulators, would rescue the pie company they worked for if it failed, that they would be allowed to keep any money they might make in the short term from selling shit as mince, and that they would in all likelihood be given a bonus for their efforts.

This bears no relationship whatsoever to market capitalism, even at its most ruthless and brutal. This is a form of plutocracy in which certain wealthy individuals are given a license to steal and immunity from any consequences that might arise from the theft.

The confusion about this basic truth arises from an unquestioning acceptance of the definition of “the market” propounded by the plutocrats. The plutocrats have never had the slightest faith in any true kind of market, because in such a market they might fail, they might lose money, they might be prosecuted for fraud. To the plutocrats, “market” means “shell game” conducted under the protection of a corrupt local sheriff.

Capitalism becomes plutocracy, the market becomes a shell game, only when the defrauded, the “marks”, are unwilling to remove the corrupt sheriff and discipline those he's protecting.

It's time to take the folks selling the cow-dung pies out back of the cathedral and beat them to a pulp — if only to make them think twice about ever showing their faces in our town again.