Harry Truman said, “The only thing new in the world is the history you don’t know.” If that’s the case, there’s nothing newer in the world than the popular entertainment spectacles of the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

These spectacles have not vanished, exactly — they have been subsumed in modern forms like movies, theme parks and the Las Vegas mega-casino. In fact, these are not modern forms at all, they just seem modern because we have forgotten their 19th-Century predecessors.

Part of the problem is that these predecessors were mostly ephemeral phenomena, shows and world’s fairs (often shows at world’s fairs) which came and went, which were never designed to last. Vast fantastical cities would be erected in places like Paris and Chicago, built mostly of plaster meant to look like timeless marble but in fact almost instantly torn down after the fairs closed, leaving only a few durable and poignant souvenirs of the exhibitions they graced, like the Eiffel Tower, for example, which had the good fortune of being made from cast-iron.

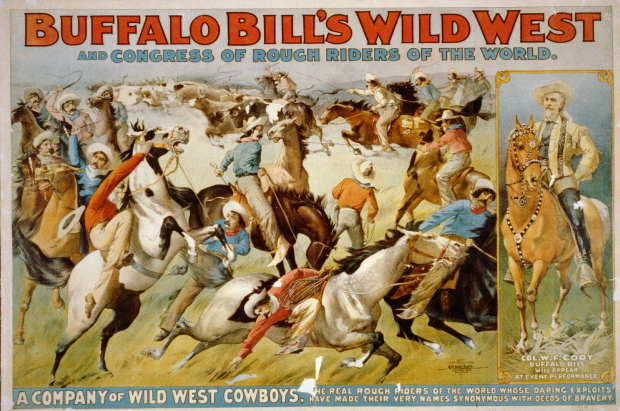

Gigantic theatrical spectacles on historical themes, like Buffalo Bill’s Wild West or Imre Kirafy’s “The Fall Of Babylon”, lasted only as long as they drew crowds or their star continued to appear in them.

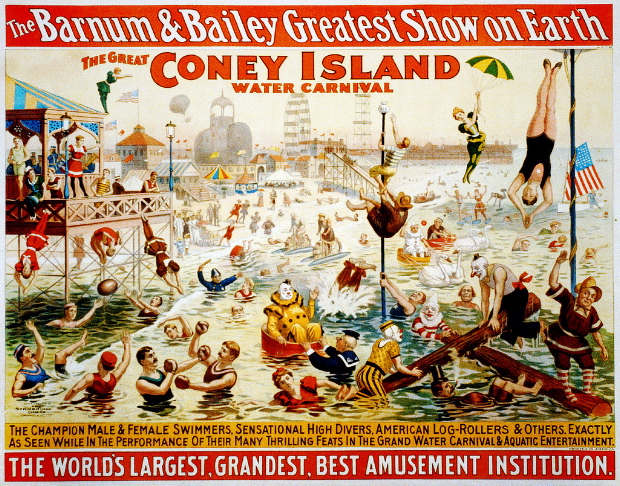

We have some still photographs of some of these exhibitions and shows, and some bits of film footage from the Edwardian era, but these can’t possibly bring back the color and kinetic dynamism which made such spectacles so appealing to audiences of their time. The colorful lithographic posters which advertised them do survive, and they give a sense of what they promised their audiences, if not precisely what they delivered to them.

The Water Carnival advertised above was in fact staged under canvas in a large transportable water tank as part of a traveling circus. I’m sure it was colorful and exciting, but it couldn’t possibly have looked the way it looks in the poster. It was nevertheless the precursor of the water spectacles staged by Fred Thompson in the gigantic water tank at the New York Hippodrome just after the turn of the last century, which in turn was the precursor of Billy Rose’s “Aquacades”, shows involving athletic swimming events and water ballets staged in outdoor venues a couple of decades later . . . and these in turn were the precursors of the films of Esther Williams made at MGM — indeed, Williams was discovered by MGM scouts while performing in one of Rose’s extravaganzas.

The Williams films were a direct inspiration for the synchronized swimming events in today’s Olympics and, in the commercial sphere, an extravagant water spectacle, O, created by the Cirque du Soleil, is currently on view at the Bellagio Casino in Las Vegas.

Who knew?

The great creators of these spectacles — Kiralfy, Thompson,

who built Luna Park at Coney Island as well as the New York Hippodrome, the

world’s largest theater, on Sixth Avenue in Manhattan, Steele Mackaye, who helped design and shape Buffalo Bill’s show — are little known today, and their monumental creations have long since tumbled before the wrecker’s ball or rotted away in theatrical storehouses, but they were the fathers of the movie spectacle, the theme park, and the Las Vegas Strip.

In 1897, Imre Kirafy, choreographer, theatrical producer, stage and world’s fair designer, rebuilt the ancient city of Babylon on a colossal scale on Staten Island, peopled it with 1,500 costumed extras, including, of course, exotic dancing girls, and re-enacted its fall. The attraction was wildly successful, but survives today only in yellowing newspaper clippings. Kiralfy has no modern biography and you can only find passing references to him on the Internet and in histories of American theater.

When D. W. Griffith recreated Kiralfy’s recreation on film, in the “Fall Of Babylon” section of Intolerance, complete with exotic dancing girls, he fashioned a modern cultural myth, a seminal moment in the history of cinema, and we can be forgiven for thinking that it sprang full-grown from his imagination . . . in Hollywood, at the corner of Sunset and Vine. How could we know that Griffith was only working from a tradition of theatrical spectacle on a grand scale that long predated his career in movies? The origins of that tradition have simply vanished from sight and mind.