Story meetings.

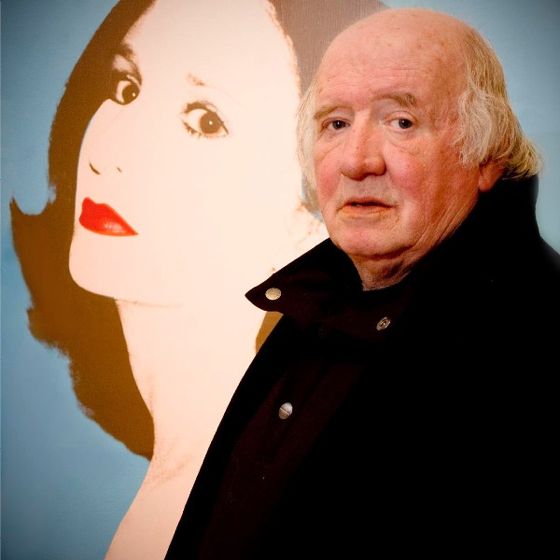

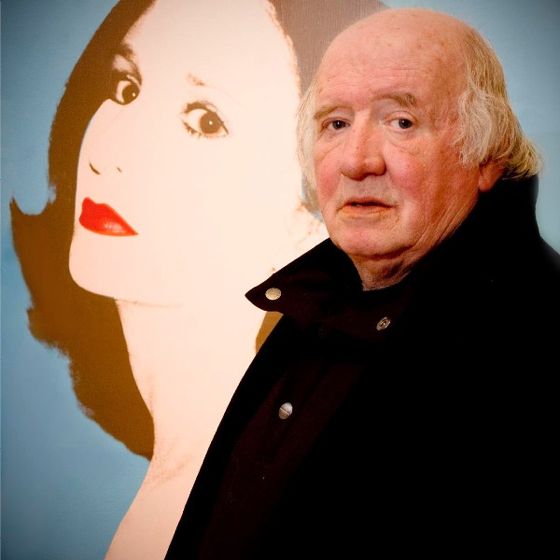

Teacher and cultural critic Dave Hickey (above, looking like the Benjamin Franklin of the 21st Century) explains what's wrong with them:

“My one rule is that I do not do group crits. They are social

occasions that reinforce the norm. They impose a standardized discourse.”

Story meetings always find the most clichéd angle of analysis, the stuff everyone can agree on because everyone has heard it a hundred times before. This is where the “problem-solving” plot comes from — because too many people in the film industry have gone to business school and are comfortable with problem-solving case studies involving corporate turn-arounds.

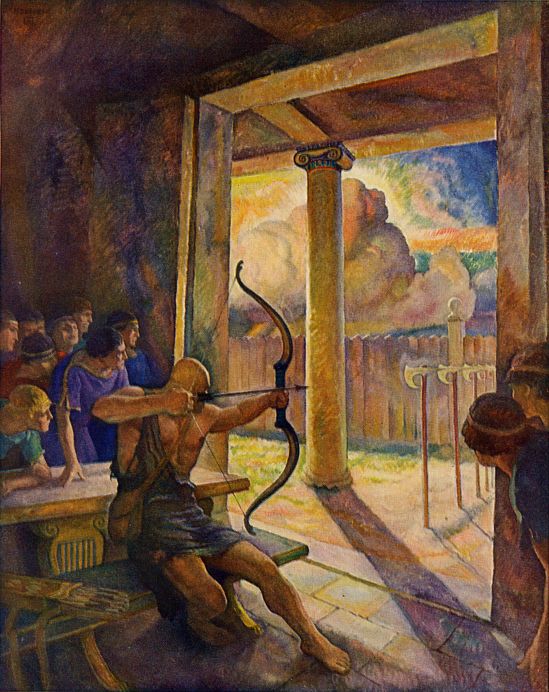

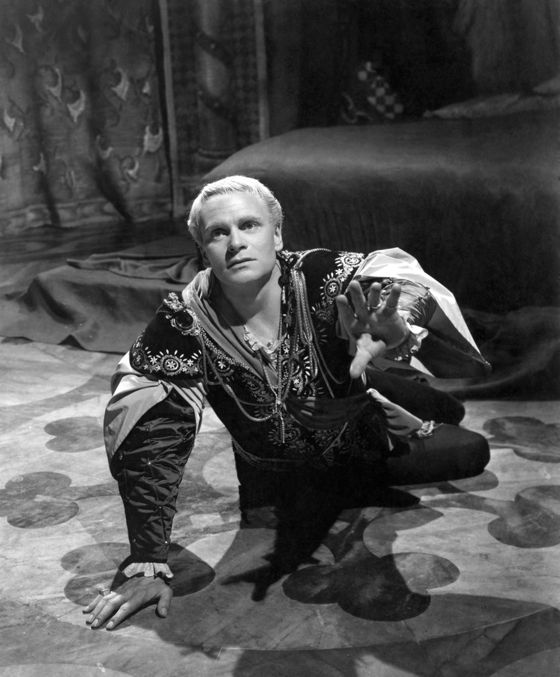

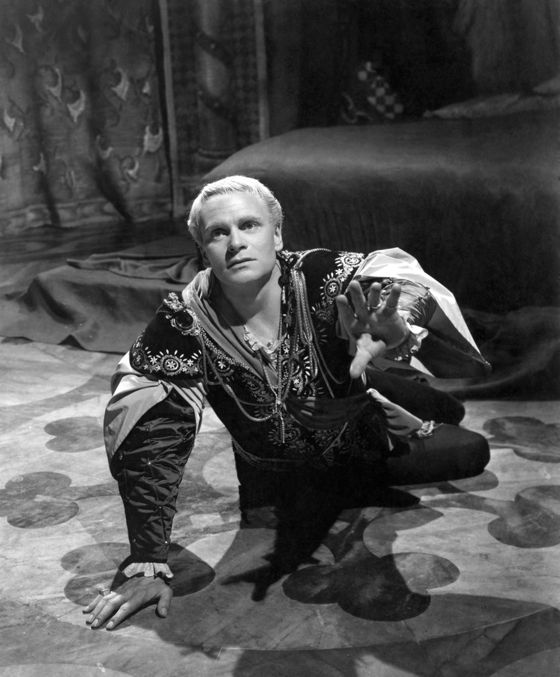

This is where the “character arc” concept comes from. Very few great characters in literature or film have “character arcs” — Achilles doesn't, Odysseus doesn't, Hamlet doesn't, Lewis Carroll's Alice doesn't, Charles Foster Kane doesn't, Ethan Edwards in The Searchers doesn't.

These characters are inconsistent and ultimately mysterious, even to themselves, as we all are. They reveal themselves, gradually and partially, through what they do, surprising and intriguing us (and undoubtedly themselves, too) along the way. They may end up in different places than the ones they started out in, for better or worse, but they don't “progress”, they don't move from point A to point Z along a perceptible curve. This is why these characters are inexhaustibly fascinating, and thus immortal.

The character arc is an attempt to reduce the complexity of human nature to a graph chart, suitable to illustrate a presentation in a corporate boardroom. Characters in great stories, like human beings in real life, change, when they do change, for irrational reasons, for unfathomable reasons — if we could think ourselves rationally into positive change we'd all be happy, well-adjusted people.

Do you know any happy, well-adjusted people? Yeah, me neither. And I wouldn't want to. They'd be robots.

And characters in great stories don't need to change at all — Hamlet doesn't change in the course of Shakespeare's play, he just reveals layer after layer of an ultimately unknowable self. We may change watching this revelation, but that's another story — another story that can't be charted on a graph.