And the update . . .

And the update . . .

Wild Turkey

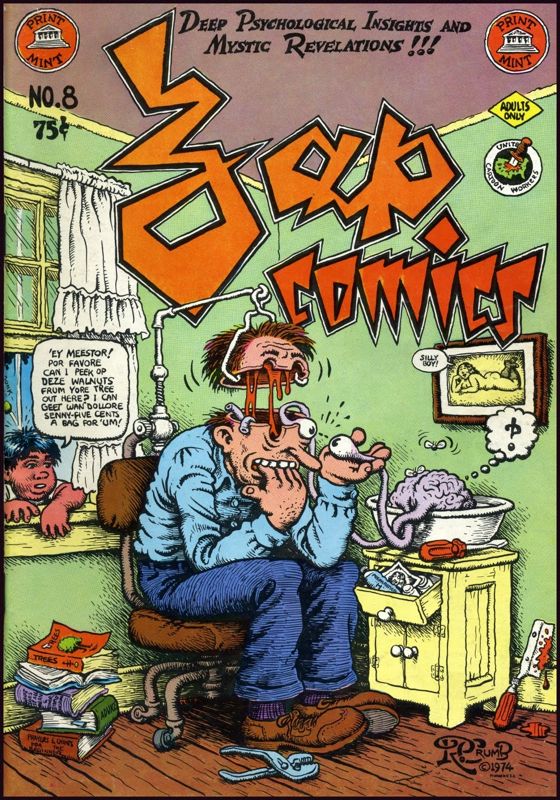

Thanks to Golden Age Comic Book Stories . . .

With thanks to Little Hokum Rag . . .

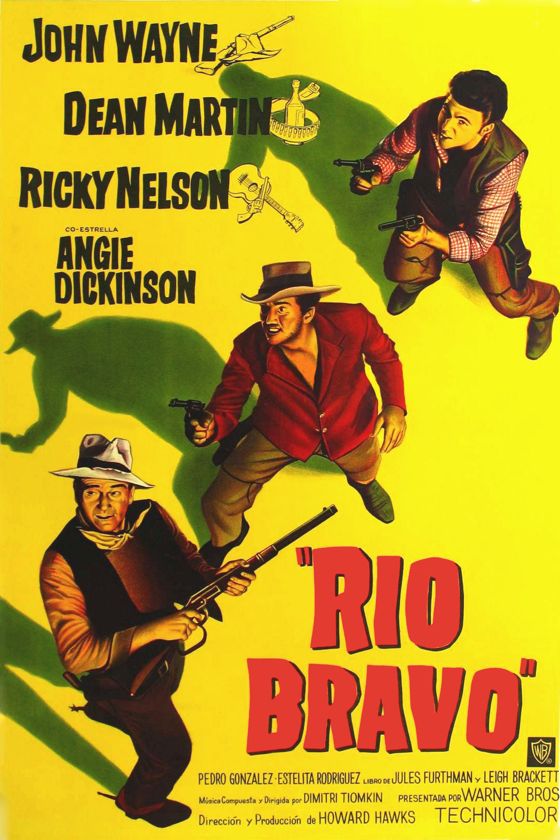

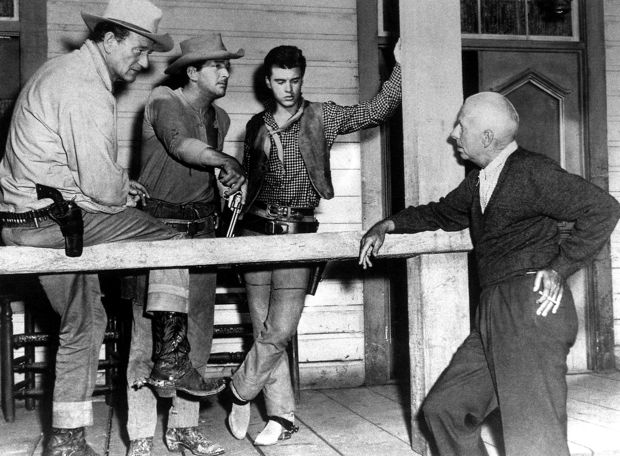

Howard Hawks's Rio Bravo, from 1959, is many people's favorite Western, and there has certainly never been one that's more entertaining. Hawks famously said that it was his answer to High Noon, which he found irritating because its hero sheriff ran around begging the citizens of his town to help him with his job. Sheriff John T. Chance in Rio Bravo, played by John Wayne, pointedly refuses help from the citizens of his town on the grounds that they're not professionals and would only get in his way. (He already has two allies — professional but flawed, just to make things more interesting — and picks up a third along the way.)

This dialectic is a little silly — there are obviously situations in which each approach would be appropriate — but Chance's is a lot more appealing, because it's closer to the classic Western idea of the hero. High Noon is about a town trying (and failing) to make the transition from frontier outpost to civilized community. Rio Bravo is governed by a different vision of the West, in which community in that sense is irrelevant — individual initiative and responsibility are the central and decisive issues.

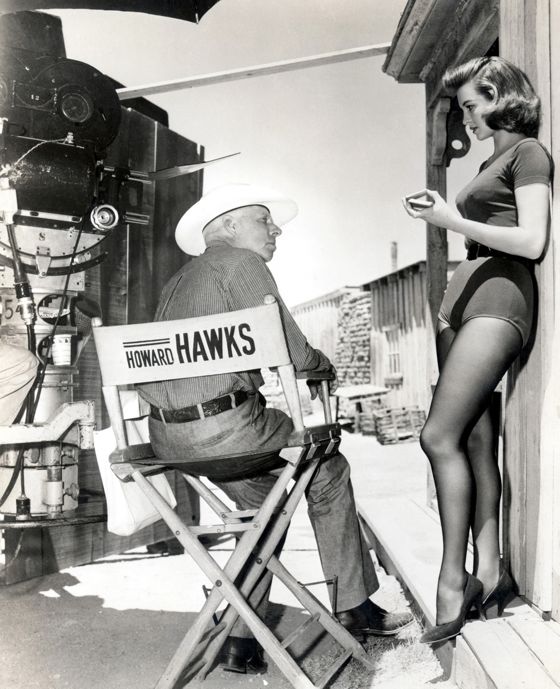

Chance's attitude also reflects a recurring theme in Hawks's work — a celebration of professionalism, of people who know how to get the job done and do get it done, however cynical they may be about the job itself. The small, closely-knit team, dedicated to a particular objective, is important to Hawks, along with the mechanics of teamwork — society as a whole doesn't concern him all that much, and is often presented as indifferent or corrupt, as it is for the most part in Rio Bravo.

Sex in Hawks's work is also more a matter of teamwork than romance — a game for two that has to be played well, and with a certain amount of diffidence. Hawks's typical women aggressively pursue men they're attracted to, but expect to be amused in return. Angie Dickinson is the hard-boiled dame “Feathers” who pursues Chance in Rio Bravo, asking nothing more than his engagement and encouragement for as long as things last. She's a virtual reprise of the Lauren Bacall character in To Have and Have Not, a drifter and adventurer who's intrigued enough by the hero to pause for a while in her wanderings to play with him.

Feathers initiates the first kiss in Rio Bravo, which Chance responds to almost passively. Then they kiss again and he's more active, at which she pronounces herself satisfied — “It's better when two people do it.” It's a direct echo of Bacall's famous line in To Have and Have Not in which she tells Bogart that kissing is “better when you help”.

Dean Martin gives a surprisingly strong performance as Dude, a broken-down deputy who has to rehabilitate himself in order to help his friend Chance. Ricky Nelson plays a hot-shot kid gunslinger whose professionalism impresses Chance and leads them into an inevitable alliance.

Nelson's performance is lackluster — he's in the film for marketing purposes — but Hawks uses Wayne's authority as a star and Western icon to lend Nelson's character “Colorado” substance. If John Wayne approves of the kid and takes him seriously, who are we to second-guess him? Colorado has a moment of fancy gun-play in a shootout, but his heroism doesn't really register until Wayne tells the other guys how good Colorado was.

Nelson's presence, and the cheerful tone of the film, let us know that nothing much more than entertainment is at stake in the tale. John Ford is always interested in exposing the moral contradictions of his heroes, in examining the moral landscape of America itself. Hawks is just interested in hanging out with some cool people and watching them do their thing. Rio Bravo unfolds at a leisurely pace but is never dull for a moment — because the company is so good. The only real suspense lies in wondering if the characters will be cool enough when their big moments arrive. Of course they always are — and then some.

The spirit of fun that infuses the film is almost tongue-in-cheek — one can see in it a foreshadowing of the Sergio Leone approach to the Western, in which every Western cliché seems to have quotation marks around it, seems to be delivered with a wink. Unlike Leone, though, Hawks is never interested in subverting or upending the clichés — just in having some fun with them, in the most efficient and elegant way possible.

Molly Haskell has called Rio Bravo “a movie one loves and returns to as to an old friend” — and that's not faint praise for a film which lasts well over two hours and proceeds, as I've said, at such a leisurely pace. It's a “town Western”, too, one that never strays from the town it's set in, that takes place mostly in interiors and on one street on a studio lot. But Hawks explores this narrow geography thoroughly, makes us feel at home in it, and his cinematographer Russell Harlan lights it warmly. The film makes us cozy and comfortable, gives us time to know and savor the quirks and qualities of its characters.

This may make it seem like a simple film, but it's hardly that — the skill required to make something this “simple” so consistently fascinating and enjoyable is hard to value or praise too highly. It takes the kind of cool and impeccable professionalism that Hawks admires and celebrates so agreeably in his protagonists.

A new Majestic Micro Movie by Harry Rossi — a movie as majestic as the sea itself!

Watch it here:

The Ocean

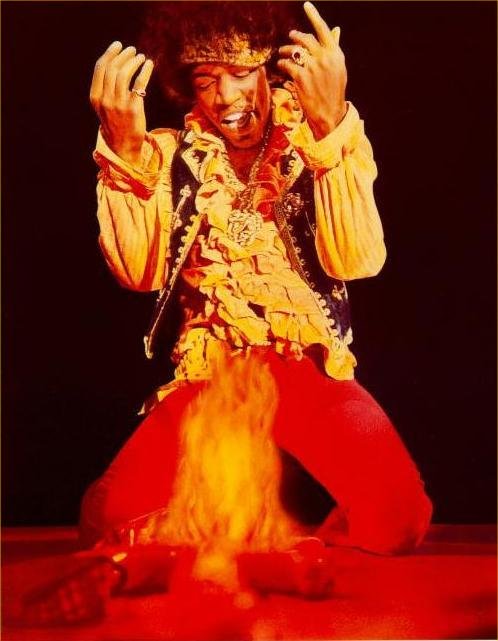

I was 9 when the Sixties began, 13 when they began in earnest with the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the advent of The Beatles. The decade sucked up all of my teenage years and brought many cultural shocks, from the Civil Rights Movement to Dylan's minatory prophesies, more assassinations, fighting in the streets over the Vietnam War and the sublime derangements of Jimi Hendrix and Jean-Luc Godard.

I went off to college in the Bay Area in 1968, grew my hair long, wore Nehru jackets and sandals made out of tire treads. I eschewed illegal drugs — my little stab at non-conformity — but drank plenty of Ernie's Burgundy and took up the smoking of cigarettes. I hitch-hiked all over the country and once panhandled for spare change on a street corner — living out a fantasy of dereliction, all the while knowing that I had a nice middle-class family to return to if things ever got really desperate. (Such was the depth of hippie rebellion.) I was at Altamont where everything came crashing down in spectacular fashion.

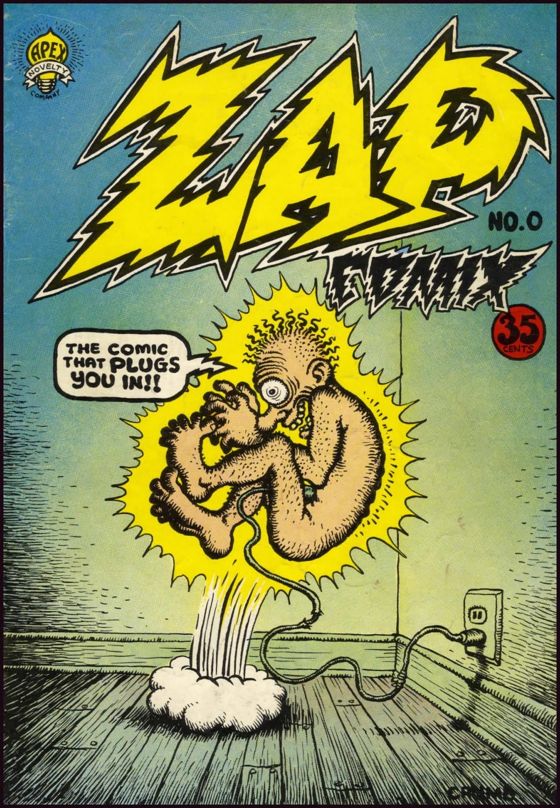

In all that madness, I don't think any cultural artifacts impressed me as deeply as the works of R. Crumb. When I bought my first batch of Zap Comix at the City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco and began to devour them, I had a sense that I would never look at America and American popular culture in quite the same way again — and I never did. Crumb represented a permanent mind-fuck.

The Western isn't dead — it never was. It abides, through fruitful times and fallow times — a rich soil always capable of putting up unexpected shoots.

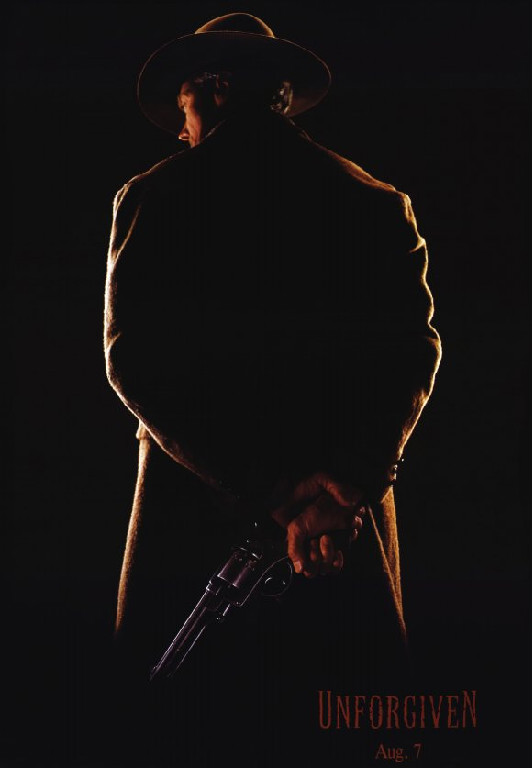

A bestseller, like Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove, can inspire a classic Western, which the mini-series based on the book surely was. A great screenplay, like David Webb Peoples's Unforgiven, in the hands of a great director, can produce a critically-acclaimed box-office hit.

Unforgiven was much more than that, of course — it is now generally recognized as one of the greatest Westerns ever made, one that can stand comparison with the classics of the genre, and with all but the very best Westerns of John Ford.

Since Unforgiven was made in a fallow time for Westerns, it naturally reflects this. It is part of a tradition that arose in the Sixties when the Western seemed to be dying off as a viable commercial genre — the twilight Western. This tradition concerns aging heroes who set off on one last adventure, mirroring a feeling that the Western itself might be heading for the last round-up. Valedictory in tone, it actually wants to assert that the aging heroes are still with us, that their values still matter.

The twilight Western tends to be revisionist, painting a darker and grittier vision of the Old West than the older classics, and often incorporating a female perspective — these are its nods to modernity, on one level, but also its witness that the Western genre is still alive, still capable of evolving, of reflecting contemporary issues and ideas.

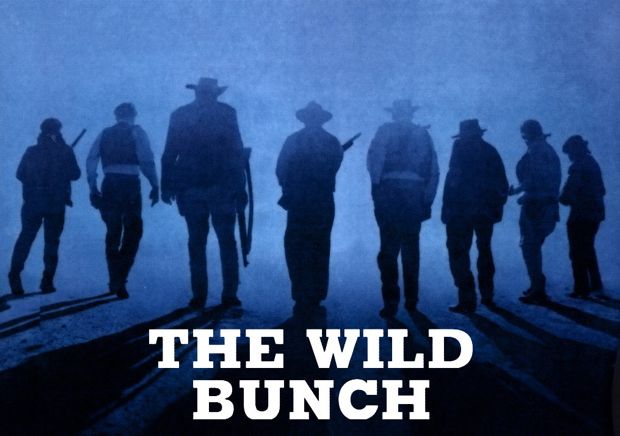

The makers of anti-Westerns, like Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, believed that the Western was played out, and proceeded to deconstruct it, to suggest that the Western myth was all a lie — that was their nod, or surrender, to modernity. It was a delusion, as the phenomenal success of movies like Lonesome Dove and Unforgiven proved, but a delusion with great cachet for filmmakers and studio executives who came of age in the Sixties and Seventies. For them, the thrill of killing off the traditions of their fathers festered and metastasized into an industry truism — modern audiences don't like Westerns.

The truth is that modern audiences don't like anti-Westerns, the only Westerns that present-day Hollywood thinks are cool. Every time a new anti-Western flops, it seems to confirm the truism. When a new Western that celebrates the classic virtues succeeds wildly, it's seen as an anomaly.

If the Coen brothers' True Grit, opening this Christmas, succeeds, Hollywood will not see it as the success of a Western. As a Hollywood producer recently remarked to a friend of mine, reflecting on a possible revival of interest in Westerns, “The Coen brothers are their own genre.” There's some truth in that, of course, but only up to a point, and that point is reached when the Coen brothers tackle a classic Western tale like True Grit.

Eventually, the glamor of the anti-Western will die out, with the rise of new generations of directors and producers untainted by the follies of the Sixties and Seventies. The Western will still be here, its soil richer than ever from a long fallow time, ready to produce a new harvest of stories and adventures. The passing of the twilight Western will signal the true renaissance of the form — new, young stars will take up the reins as protagonists of the revived Western, and blaze their own trails into the heart of America's most precious and enduring myth.

The tide is high but I'm holding on . . .

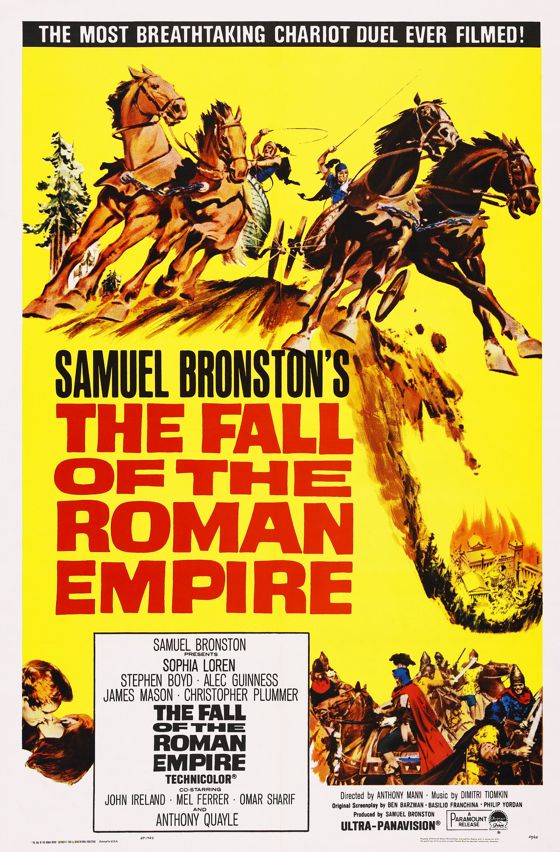

Magnificent in many ways, breathtaking visually in many sequences, Anthony Mann’s The Fall Of the Roman Empire, from 1964, is nevertheless an epic failure. Unlike the Roman Empire, the film’s downfall can be traced to a single cause — a single miscalculation in casting. A film as big as this needs an emotional rudder, a figure at its center the audience can steer by, and Stephen Boyd is just not able to be that. Very few actors could, but Boyd is singularly ill-equipped for the task.

Boyd had a slightly fey quality, a hint of weakness in the eyes and mouth, which worked wonderfully when set against the stolid heroism of Charlton Heston in Ben-Hur. It fueled the slight suggestion of a homo-erotic attraction between the two antagonists. As the heroic lead of The Fall Of the Roman Empire, by contrast, Boyd creates a kind of black hole of charisma at the center of the picture, especially since he is paired romantically in the story with Sophia Loren, who is, just in her own person, an epic of femininity. Between the Roman Empire and Loren’s empire of female flesh, Boyd doesn’t have a fighting chance.

Boyd was an actor of limited range, and heroic grandeur did not fall within it, as it did for Heston, limited as Heston may have been in other ways. (Heston and Kirk Douglas both turned down the Boyd role — either one of them, I think, could have saved the picture.) Boyd here summons at best the slick authority of a Las Vegas lounge singer — not someone one would entrust with the command of a Roman cohort, much less the rule of Rome itself. It doesn’t help that Boyd is given a preposterous hair-do, with curled, poofy bangs, obviously dyed. If this film hadn’t cost so much money, you might almost believe that the bangs were some kind of cruel joke slipped into the film by a prankster on the production.

The inadequacy of Boyd can’t quite sink the first half of the film, up to the intermission. This section, set on the frontiers of the empire in Germania, boggles the mind with its size and sweep and beauty. We will never again, in the age of CGI, see images like this on film.

The film shifts to Rome after the intermission and, despite a parade of staggering and mostly magnificent sets, unravels quickly as a drama. It becomes a test of wills between the neurotic Caesar Commodus, played with relish and wit by Christopher Plummer (below) . . .

. . . and Boyd’s Livius, his second in command. At stake is Livius’s love for Lucilla, Commodus’s sister, played by Loren, as well as the survival of the Roman Empire. It’s hard to care about either with Boyd as the protagonist in both struggles and a bit of a relief when Rome finally implodes.

Once you accept the film as a failure, though, you are free to appreciate its wonders — some of the most spectacular recreations of the ancient world ever committed to film, all shot with Anthony Mann’s usual genius for plastic composition and action. It’s a thrill, as well, to watch the way the camera worships Loren, who gives a very good performance here, along with a wonderful cast in almost all the supporting roles. Fans of Ridley Scott’s Gladiator will also discover that its original screenwriter David Franzoni found much of his inspiration for that film in The Fall Of the Roman Empire, set in the same period, with a number of set pieces and major story elements in common.

But, as I say, Mann’s film is a rudderless ship, narratively and emotionally — one soon ceases to wonder where it’s going, because, like the Roman Empire itself in its twilight years, it’s so obviously going nowhere.

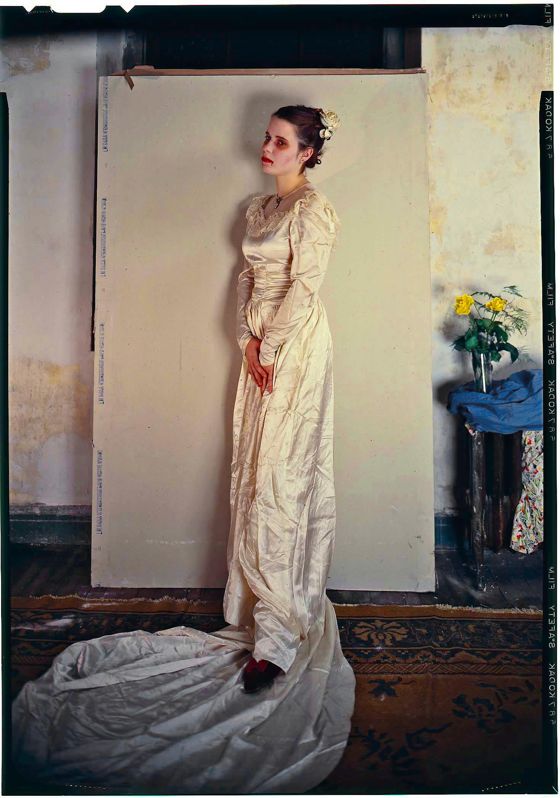

This is Eli Johnson, as she then was, whose latest birthday I wrote about here, on Halloween some years ago, when she was just 17 (and you know what I mean), photographed by Lang Clay.

The portrait is like a John Singer Sargent gone slightly awry.

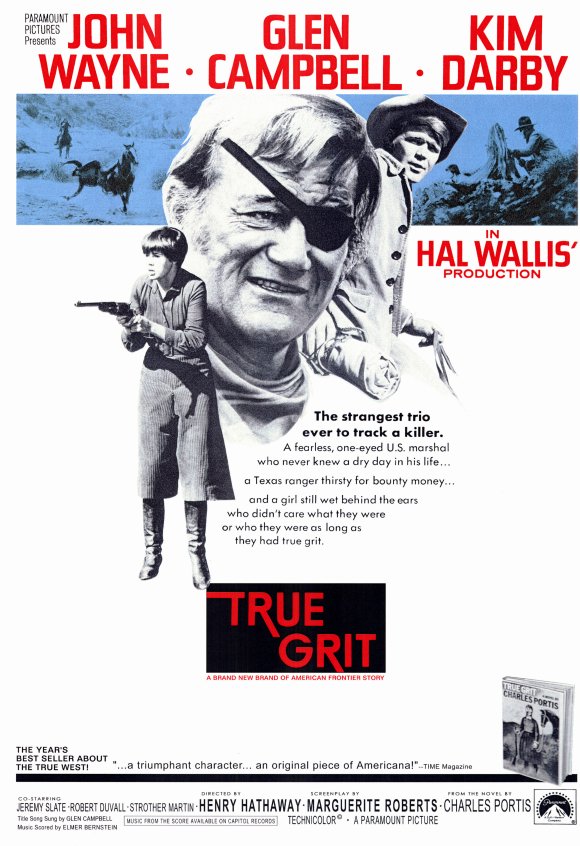

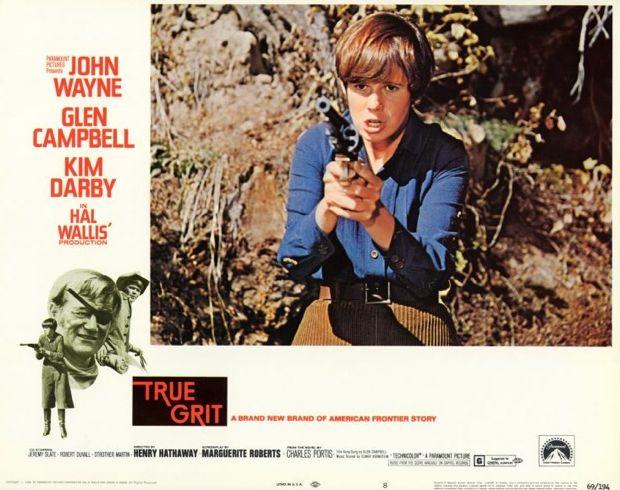

Henry Hathaway’s film True Grit, from 1969, is a wonderful entertainment, respectful of, if not exactly faithful to, the great Charles Portis novel on which it’s based.

The powerful emotional impact of the novel is achieved by indirection, by characters who don’t speak about what’s really going inside them because they’re rarely aware of it. We read their inner lives though their actions, which are often surprising, startling, even shocking. Hollywood is generally afraid of tales told this way, afraid that audiences won’t get the point, so the adaptation of True Grit brings the emotions and motivations of the characters to the surface. Paradoxically, this leaves the viewer with less to respond to.

It’s clear from the start in the film where the friendship between the teen-aged Mattie Ross and the grizzled frontier marshal Rooster Cogburn is going. It’s a pleasure to watch it go there, but one can’t fully enter into the journey as a participant. John Wayne, who won his only Oscar for his portrayal of Cogburn here, is exceptionally good, working against his usual buttoned-up hero’s persona, but reveals the character’s decent and genial side too quickly.

Kim Darby, as Mattie Ross, also gives a fine performance, but because Darby was 21 when she made the film, Mattie’s precocious self-possession can’t help but lose some of its edge. (In the book, Mattie is 14.) Glen Campbell, then a popular cross-over country singing star, was cast in the third lead as Le Boeuf, primarily as a marketing ploy one assumes. He acquits himself well enough, but always looks out of his league among the other fine supporting players like Robert Duvall, Dennis Hopper and Strother Martin.

Although Hathaway directs the film in a classical style, with beautifully composed images (discounting a few ill-advised zooms), the film tries in other ways to be contemporary. Elmer Bernstein’s score, often echoing the one he did for The Magnificent Seven, is generally light and buoyant — it doesn’t enforce the darker emotional currents of the tale. The script incorporates a lot of Portis’s fine dialogue but emphasizes the cheerful and comic side of the novel, at the expense of its paradoxes and contradictions. The disturbing undertow of the book is only suggested.

Paramount probably thought it was taking quite enough chances on this film, a Western with a strong female protagonist that featured John Wayne as a slightly less than heroic drunk — but in truth it was only keeping up with the times. In the 1960s, Hollywood and the culture were becoming self-conscious about the conventions of the Western in an era of national doubt about the American dream, undermined by a controversial war in Vietnam and rowdy social upheavals at home.

1969 also saw the release of The Wild Bunch, Sam Peckinpah’s savage and cynical deconstruction of the Western genre. True Grit was a big hit at the box office, The Wild Bunch not so much, but a critical favorite. The culture was clearly open to a different kind of Western. It’s a shame that filmmakers chose to follow in Peckinpah’s tracks, instead of Hathaway’s or even Portis’s. Dark and unconventional as the novel True Grit was, it still managed to celebrate, in its quirky way, the humane and noble values of the classic Western, introducing a convincing female perspective in the process. Portis’s vision might have led to a renewal of the Western film — Peckinpah’s led to its virtual destruction as a reliable Hollywood genre.