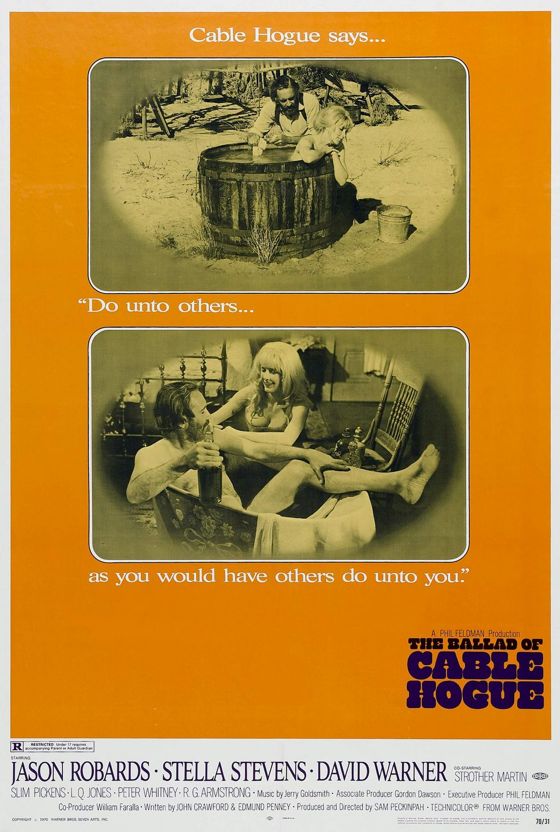

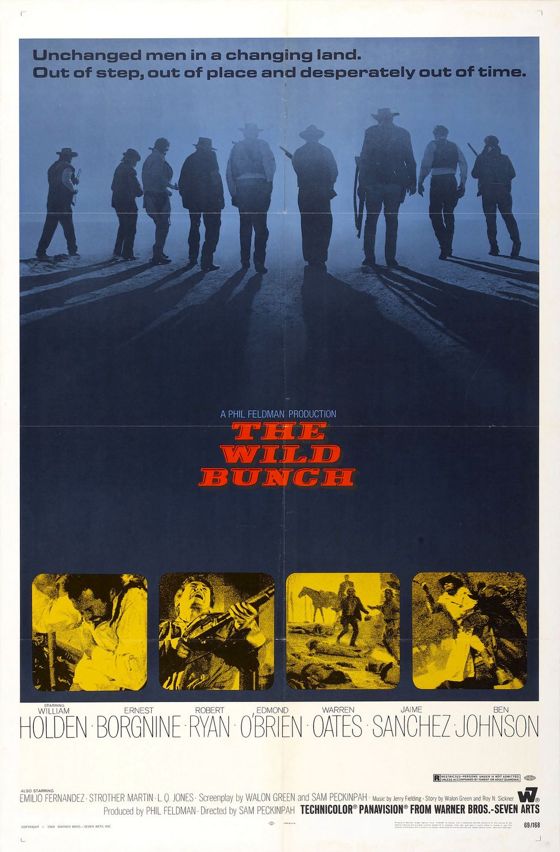

[Note: If you’re a big fan of The Wild Bunch, please don’t read this post — it will really piss you off.]

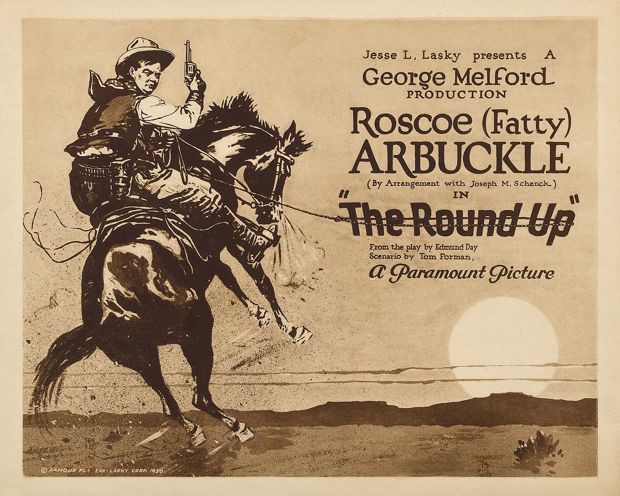

I know that The Wild Bunch has a lot of cool stuff in it, a lot of cool lines and situations and scenes. I know how startling a film it was when it first came out, because I saw it when it first came out and was startled. I know its historical importance in inaugurating the era of the anti-Western. I know that it was made by a filmmaker of genuine genius and has one set-piece action sequence that’s very close to being brilliant.

But I also know that, overall, it’s badly written, badly shot and badly edited. It’s a mean-spirited, crappy little movie, for all its reputation, and its commentary on the Western genre, its revision of that genre, is puerile and meretricious. It was made by a man who understood and loved the genre but sold his birthright for a mess of porridge.

If your positive feelings about the film are based on viewing it as a young person, then I can understand them — when I was a child I spake as a child, too. But when I became a man, I put away childish things. If your positive feelings about the film are based on a recent viewing and careful consideration, then I either don’t respect your judgment or I don’t like you.

There are some things a man can’t ride around, and for me The Wild Bunch is one of them.

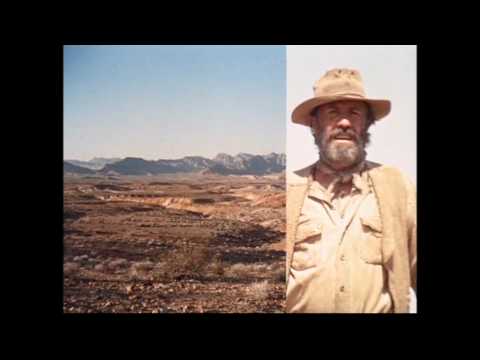

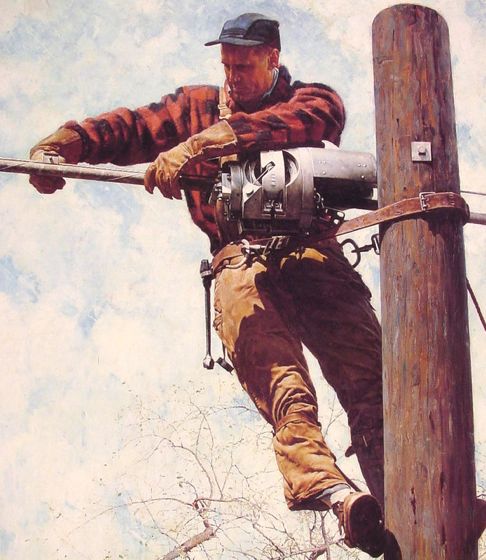

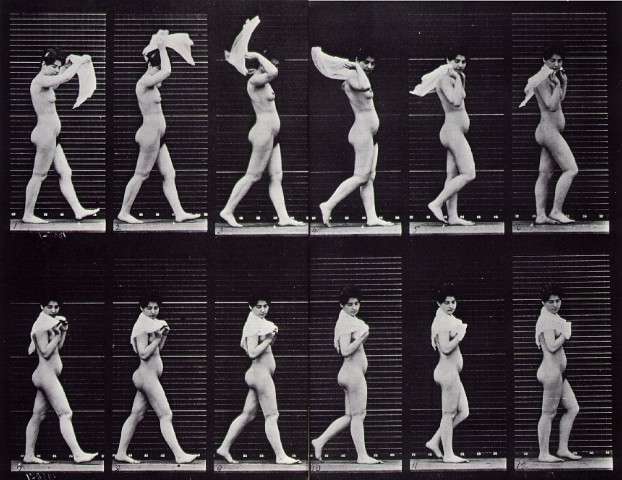

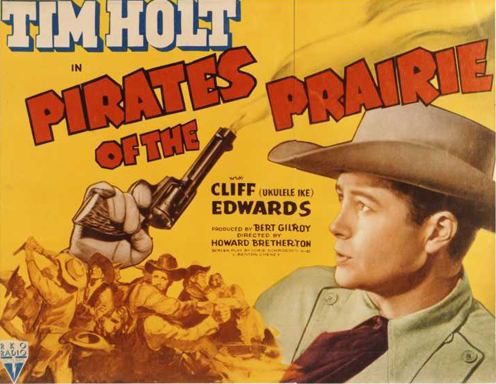

This was Sam Peckinpah’s fourth Western feature. The second, Ride the High Country (above), was one of the great twilight Westerns — a tale of the passing of the West and of the men who tamed it and of the code they lived by. Peckinpah didn’t write that film. He did co-write The Wild Bunch. It has elements of the twilight Western. Its protagonists are aging outlaws off on one last adventure just before WWI — but these men have only the crudest sort of code, which basically boils down to the idea that there should be honor among thieves.

They think nothing of murdering innocent bystanders to get what they want. They tolerate one of their band murdering a former lover because she’s left him for a crud. They’re content to murder U. S. soldiers in order to steal weapons for a corrupt Mexican tyrant, in return for cash. They’re not above using unarmed women as shields in a gunfight.

Yet somehow Peckinpah sees honor in these men — because they like to do things the hard way (why?) and because they stick together. In a famous scene, the leader of the outlaw band played by William Holden says, to quell an argument in the ranks, “When you side with a man you stay with him. If you can’t do that you’re just some kind of animal — you’re finished.” But if you side with a man in order to do bestial things, what the hell does a code like that add up to? Nothing much, really.

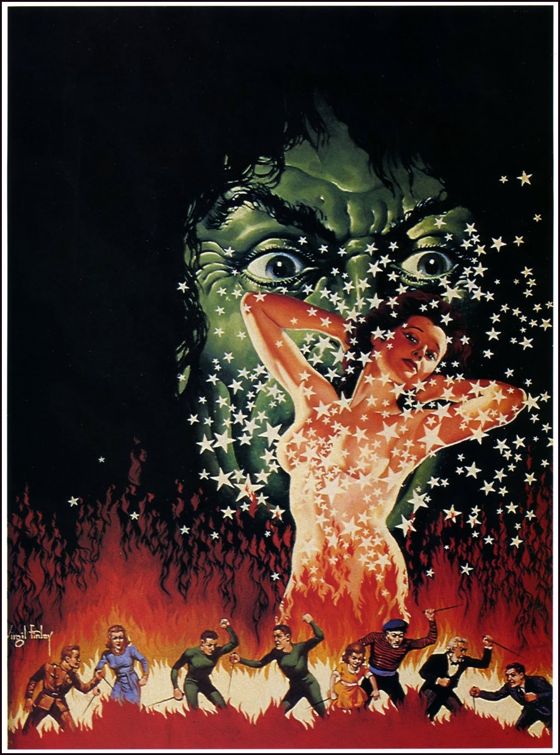

The film ends on a note of sacrificial bravery, or suicide by Federales, if you want to look at it that way, and it summons up enough of the old Western imagery to make you forget for a moment the real character of these men, brave but unprincipled by any conventional or admirable definition of the word, sort of like modern-day terrorists. Peckinpah offers an image of redemption that may fire the blood but cannot convince the heart.

It being 1969, Peckinpah the screenwriter offers other apologies for the brutality and cynicism of his protagonists. The bystanders they kill are part of a hypocritical and corrupt society. The soldiers they kill are incompetent and of course, by implication, wear the uniform of the country that was at the time ravaging Vietnam.

It’s all crap of course — an attempt to burnish male violence and misogyny with some sort of vague social criticism. The outlaws make crude jokes amongst each other and then laugh really hard over them — when you hear that totally unconvincing laughter, you know it’s just a cue to the young men in the audience to approve their own lowest locker-room sensibilities. In the paean to the men that ends the film, Peckinpah offers this rough-house laughter as a kind of transcendent image of the life force of the outlaws. It still rings hollow.

Peckinpah indulges his own adolescent insolence frequently in the film. He knows how to make beautiful shots of horses moving through landscapes, but his big equestrian stunts are all about tormenting horses and making them look awkward and ugly.

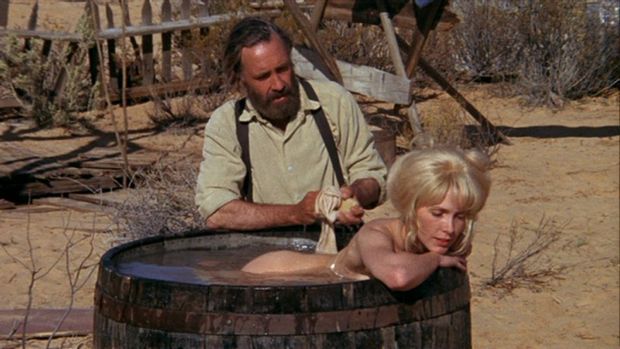

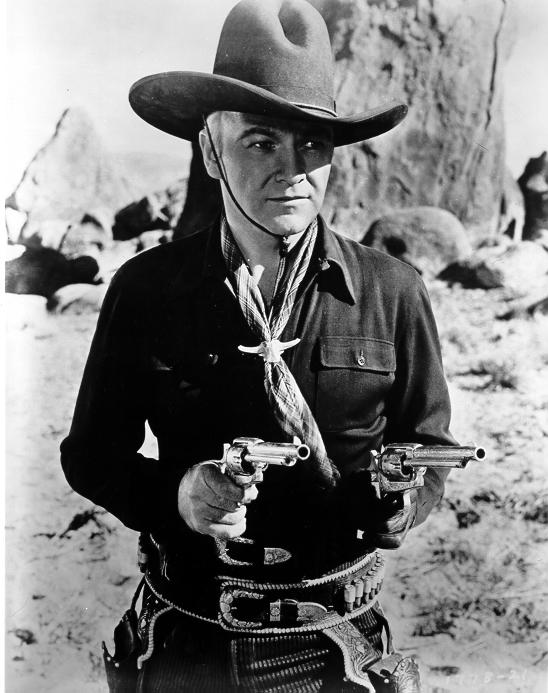

He seems to take a special delight in degrading the aging icons of the Western genre, having them do shameful things — Holden occasionally but Ben Johnson often . . . Johnson who had been for John Ford the symbol of grace in the saddle and moral grace as a hero. To show Johnson’s character drunk in a tub of water pawing a half-naked Mexican whore is to direct a gob of spit straight into Ford’s one good eye.

There are many beautiful images in the film, but many more which are turned into mush by telephoto lenses and zooms.

This style of shooting made the film seem new — in 1969. Today, it simply dates the work, making it look cheap, like something shot for television.

There is one almost wholly admirable set-piece involving a train robbery, which is well staged and well shot and well edited — it’s the work of a filmmaker who knows what he’s doing. But other action sequences are incoherent to the point of being unreadable, with fast cutting and shock zooms that give the impression of excitement by purely cosmetic means.

The film does have a few gracious moments — crepuscular mood pieces in which the nostalgia for past times is almost touching . . . would be touching if we could imagine that these men had ever been more than thugs. And there’s a mystical love for Mexico, for the sweetness of certain aspects of Mexican culture, that really is touching, even if it hasn’t got much to do with the rest of the film.

After an initial robbery gone wrong the “wild bunch” retreat south of the border and have a brief idyll in a small Mexican village. As they ride out of it the next day the villagers serenade them, and Peckinpah films their mounted procession in beautiful slow tracking shots. It doesn’t make a lot of sense — why do the villagers seem to worship such men as departing gods? — but it’s very sweet.

The Wild Bunch got its juice when it came out from its graphic violence and its swaggering nihilism — for its daring in deconstructing the myth of the old West created over generations in the movie Western. That sort of frisson has a short shelf life, though. The anti-Western cycle that this film inspired exhausted itself very quickly, and soon the Western was more or less finished as a commercial proposition. How many times can you deconstruct something that’s already lying scattered around in pieces on the ground?

Guys who thrilled to this film in their youths may have a certain nostalgia for its crude, chaotic energy, like the crude, chaotic energy of adolescence itself — and we can’t very well begrudge them this. But it’s no movie for grown men, and it was a calamitous event in the history of the movie Western and thus in our culture at large.