Bouguereau’s figures are so solid that when he sets them floating in the air the effect is unsettling, uncanny, but in a pleasant way, as flying in dreams is pleasant.

Category Archives: Art

A NORMAN ROCKWELL FOR TODAY

America is at war right now but you'd never know it from any kind of

personal experience, unless you're serving in the military or know

someone who is. Most of us

are asked to make no sacrifice, there is no meaningful national debate

about the war's prosecution or aims — just a lot of

ideological posturing, on both ends of the political spectrum.

With a volunteer army,

aided by thousands of private mercenaries, there is no direct pressure

on the nation as a nation to come to terms with what's happening.

They are fighting the war for us, unless they happen to be our own sons, daughters, fathers, mothers, husbands, wives.

Whatever you think of the war, I think you have to admit that the

current administration has committed the one unforgivable sin for the

leadership of a democracy — sending soldiers into a war without the

broad commitment of the nation behind them. Any war that we, the people, don't fight together is bound to turn into a bad one and very likely into a losing one.

Look at the image above by Norman Rockwell, from a Saturday Evening Post

cover. The young soldier, obviously just back from the Pacific

Theater, is a Marine. Viewers of the time would know that he most

likely is just back from Hell, from Iwo Jima or Peleliu or Okinawa — that he has

participated in unimaginable horrors. There is no glimmer of

triumph or satisfaction in his face, just a sense of awe, of almost

bewildered hardness. The folks who make up his audience seem to

appreciate, even if there's no way they could possibly understand,

what's he just done for them, and one thing he's just done for them is

separate himself from their world irrevocably, forever.

They seem to comprehend this — they all seem suffused with the gravity of it, they all seem to take responsibility for it.

This is so far beyond catchphrases like “We support our troops.”

The image reflects a moral complexity, a moral tenderness, that only art can evoke — an

ideal of citizenship that seems to have vanished from our democracy.

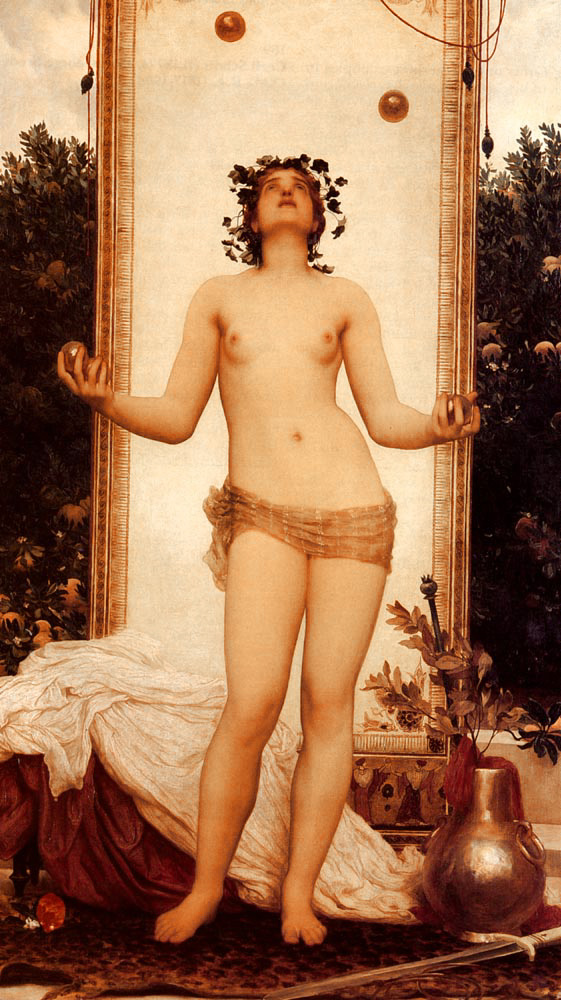

LORD LEIGHTON: A VICTORIAN ARTIST YOU SHOULD KNOW

Lord Leighton was generally considered the dean of Victorian academic painters.

He combined the decorative stylization of the early Pre-Raphaelites with a more photo-realistic draftsmanship, an approach which made his work popular with a wide public and influential among his fellow painters.

The painting above, exhibited in 1855, caused a sensation and

established his reputation. An enormous, 17-foot-long work

depicting a procession in Renaissance Italy, it was admired by Queen

Victoria, who bought it.

Leighton also did works in a style that might be called magical

photorealism, like the one below, which reminds one of similar images

by Bouguereau:

He could also, like Bouguereau, be frankly sensual in a more naturalistic mode:

Like Alma-Tadema he did vexing evocations of the ancient world:

His historical paintings could have strong narrative and theatrical qualities, like this one, Dante In Exile:

On top of all that he produced some fine portraits, like this famous image of the explorer Sir Richard Burton:

All around, Leighton was really cool.

COKE FLAG

I painted the image above on the wall of a farmhouse in Vermont

sometime in the late Sixties. For some reason the owners of the

farmhouse decided not to paint over it and so it has survived for going

on 40 years, as I just discovered via this photograph of it, taken by a

friend last Sunday when he was visiting the place.

The design is kind of cool, even if the draftsmanship leaves something

to be desired. It still sums up what the Sixties felt like to me

at the time, when the idea of being patrotic about American culture

made more sense than being patriotic about the American state.

A WATERHOUSE FOR TODAY

You could get lost in the spatial complications of this painting, Destiny

by John William Waterhouse, which take a while to sort out. The

sorting out is part of the artist’s strategy for drawing you into the

image — as the female figure’s dream of the adventures those ships

could take her on becomes your own. For her the ships are reflections

in a glass, for you they’re paint on canvas — dreaming makes them both

real.

FROM CANVAS TO SCREEN

Here is Anders Zorn at his most academic. The composition offers a dramatic illusion of deep space, with an optical integrity which evokes the photograph — but it’s all inflected with the suggestion of narrative, as we’re invited into the darkened area just off the ballroom where private intercourse is taking place.

And yet for all this we still have Zorn’s delightful treatment of the

surface of the canvas, with its sensual strokes reminiscent of the

Impressionist style, its magical ability to render the subtlest play of light.

The total effect can only be described as cinematic — and wouldn’t it

be nice if cinema offered more images as exciting as this one, visually

and plastically?

I think it’s possible that this image was in the back of D. W. Griffith’s mind when he composed the shot below from Intolerance, with its own darkened area just off a ballroom that opens up brightly behind it:

As I’ve written before, we tend to see early film as a medium emerging

from the Victorian stage, but Griffith himself wrote this about Intolerance:

“You will see the world’s greatest paintings come to life and move and have their being before your eyes.”

The important thing to remember is that painting itself, even before

the invention of movies, was aspiring to the condition of cinema.

The spatial depth of Zorn’s image, its desire to evoke movement in

space, found a kind of fulfillment in the cinema, especially in the

cinema of D. W. Griffith.

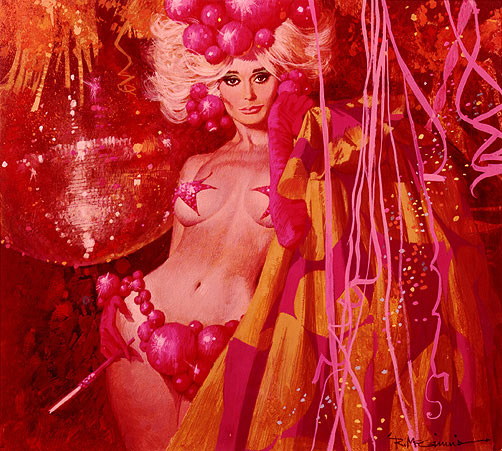

A MCGINNIS FOR TODAY

Here’s Robert McGinnis‘s evocation of a Vegas showgirl. A master of paperback cover art for pulp fiction, McGinnis got the point-of-sale appeal of such covers down to a science. I’d buy whatever book this painting graced the cover of, even though I knew in my heart that it would never live up to the image’s promise.

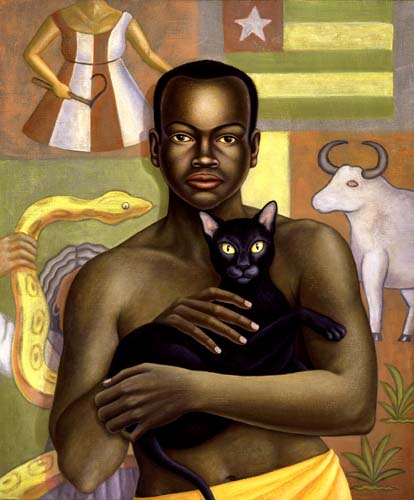

A CREHORE FOR TODAY

In this imaginary portrait of a boy from Togo, Amy Crehore plays with

space in an interesting way. The low relief of the central figure is

accentuated by placing him against a flat wall decorated with flat

images. It's as though he's emerging from the surface of the

wall, entering space, tentatively.

POP ART

It drives me crazy when people talk about works of Pop Art as though

they somehow belong in the same category as traditional high art — as

though it makes any sense at all to talk about the oeuvre of Andy Warhol in the same breath as the oeuvre

of Jan Van Eyck, just because they tend to be grouped that way by the academy

and by art institutions. I actually think it's a sign of clinical

insanity, culturally speaking.

But that doesn't mean that works of Pop Art aren't unspeakably cool. The Lichtenstein above is unspeakably cool.

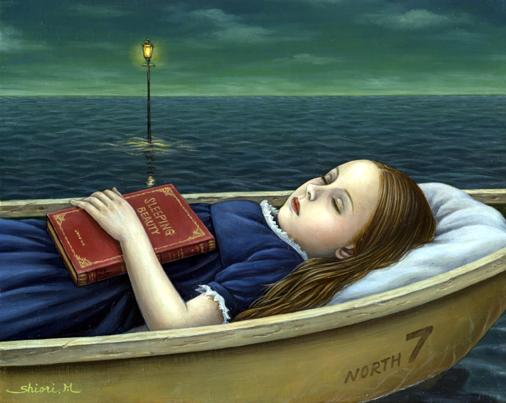

VISIONS

Here’s a link (via the ever illuminating Little Hokum Rag) to the amazing paintings of Shiori

Matsumoto. Just go to her site, click on Gallery and take a tour

through a previously uncharted precinct of Dreamland — east of

Tenniel’s Wonderland, west of the Henri Rousseau Rainforest, just down

the street from Chris Van Allsburg’s grandmother’s house. (Certain

traveling players pass between this region’s playhouses

and those on Amy Crehore’s Naughty Wondershow Theatrical Circuit,

exercising the craft and mystery of an art long thought lost.)

[Images © Shiori Matsumoto]

A ROCKWELL FOR TODAY

People who find an image like this excessively sentimental have simply

lost touch with reality — have learned to reject reflexively any work

which appeals too directly to the heart.

The image is contrived, certainly, in posing its subject between the

doll of childhood and the glamorized icon of womanhood, but there is

nothing contrived about the artist's subversive intention here.

The painting was made for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post,

which trafficked (at least in its advertising) in glamorous images of

women, like the one that is here filling a beautiful child's head with

doubt about her own attractiveness.

Rockwell's “Americana”, often seen as a sugar-coated lie, had its sharp

side. If this image doesn't make you just a little bit angry, and

deeply suspicious of a culture that seduces young women into such

self-doubt, then I think you just aren't seeing what's plainly there in front of you.

JOHN WILLIAM WATERHOUSE: A VICTORIAN ARTIST YOU SHOULD KNOW

Actually, if there’s a Victorian artist you do know, it’s probably John William Waterhouse. Prints of his paintings are quite popular, and it’s not hard to see why. He

combines the dreamy Romanticism of the Pre-Raphaelites with a bold

modeling of forms and an optical integrity that suggests a nearly

photographic realism, however free his treatment of the paint surface.

His process seems to have involved a strict linear draftsmanship to

which he applied sketchy strokes of paint as he worked out the color

scheme of the final image.

He then blended the colors into more modeled forms for the finished

work, but retained something of the freshness of his sketches.

Impressionism was a stage in his process, never an end in itself.

His primary goal was narrative suggestiveness and the creation of a

world, theatrical as it might be, which convinced the eye with the

illusion of space and stereometric forms. Note the sharp relief

of the figures in the painting at the head of this post and the

sketchier view of the coast behind them. The contrast of

treatment itself creates a sense of deeper space.

Andrew Lloyd Webber owns the painting below. I’d have bought it, too, if I had his resources — it’s just miraculous:

AN ALMA-TADEMA FOR TODAY

The title of this painting is Unconscious Rivals,

implying a narrative content that isn’t really apparent in the work

itself but suggesting how Alma-Tadema’s imagination worked. He

wanted to present the ancient world as brand new, almost

photographically convincing in visual terms, and to people it with

humans exactly like ourselves, as opposed to classical emblems of

virtue or vice. In this he was following the classical style more

closely than some of his neo-classical peers in 19th-Century art.

Even when Greek sculptors in antiquity were depicting mythological

beings, they always endowed them with an essential humanity just as

vital as their symbolic personae.

The play of light in this painting is magical yet perfectly naturalistic, and I

love the way Alma-Tadema has obscured our view of the distant sea,

which only makes us look deeper into the space of the painting to

register it. It also makes us imagine walking up to the railing

for a better view — drawing us into the foreground space as we imagine

navigating it.

A BRAND-NEW PAINTING

Amy Crehore, the artist whose blog Little Hokum Rag offers a running

record of the images that inspire her, has posted a first look at a new

painting — teasing us with just some details for now. One of the

virtues of the Internet is allowing artists to share their productions

in real time like this — the paint on Crehore’s canvas is probably not

even dry yet. It’s the virtual equivalent to a “visit to the

artist’s studio”, always considered a privilege of the well-connected

connoisseur.

[Update — the whole painting has now been revealed on Crehore’s site and it’s really wonderful.]

A TISSOT FOR TODAY

The porch and table with figures creates its own space, echoed in the space

of the pier with figures behind it, drawing our eye deeper into the

image, to the spars of the docked ship, the buildings and the course of

the Thames winding into the distance.

The girl, the captain’s daughter of the painting’s title, looks in the

other direction, counterpointing our attention. We feel that if

we just turned our heads we would see what she’s seeing.

We’re not simply looking at something — we’re inside the painting . . . we’re somewhere.