Dima has a blog now — derealization. Cool stuff there — check it out.

Category Archives: Main Page

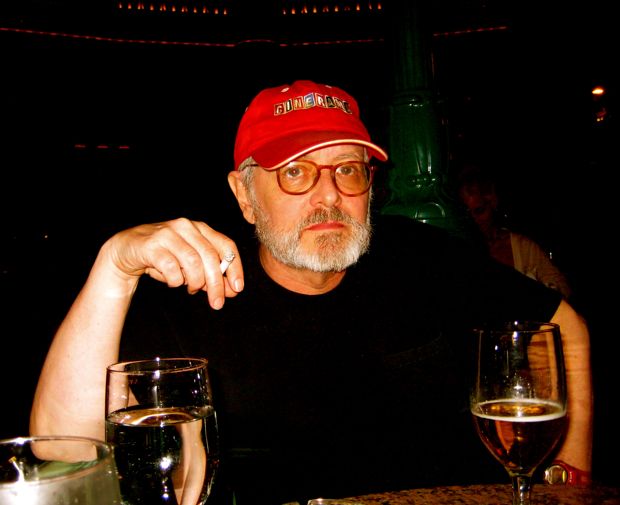

HARRY

My nephew on the terrace of Mon Ami Gabi at the Paris — in his cool Seven Samurai T-shirt. We feasted like kings — oysters, snails, chicken-liver mousse, steak, lobster.

Groups of crazed bachelorettes dressed like hookers, with plastic tiaras and beauty-pageant sashes, swirled around us but did not deter us from serious talk about movies. As you can probably tell from my expression in the photo above, the conversation has just turned to the subject of André Bazin.

FROM THE ARCHIVES: REPORTAGE DE LA PLAGE, 23 AVRIL 1999

En Californie, le printemps n’existe pas. Entre l’hiver et l’été,

l’année souffre une crise d’identité. Les jours sont entrés dans une

folie d’oscillation entre une chaleur luxurieuse et une mélancholie

d’automne, brouillée par les nuages.

On a l’impression d’habiter un film assemblé par un monteur derangé,

sous la direction d’un metteur en scène dément. Votre rôle dans la

drame est morcelé. Quelquefois on parle Anglais, quelquefois on parle

Francais. Quelquefois, la mer parle dans la voix d’une femme — et

alors l’ocean interromps le discours tendre dans la voix d’un homme.

On a l’envie des longeurs de la saison d’été, monotone et stupide, mais

fixée, lorsque elle vous dirai “Cowabunga, dude!” et on repondra avec

le sourire d’un idiot.

A CÉZANNE FOR TODAY

Nature morte . . .

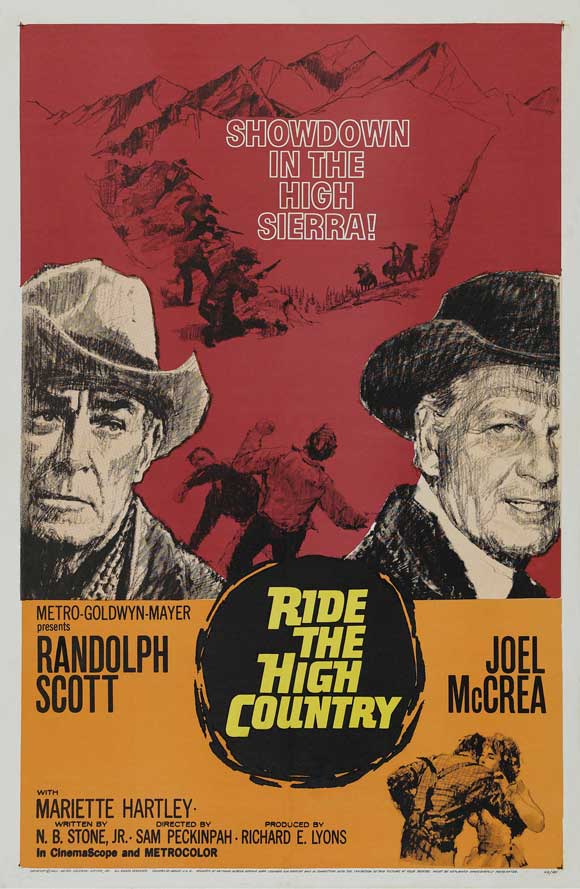

HIGH COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN

Before the anti-Western there was the twilight Western — a series of films which seemed to sense that the genre was almost played out, or at least that America no longer looked to it for wisdom and inspiration. The iconic Western stars were becoming old men in the 1960’s, and no figures of comparable stature were riding in to replace them, with the possible exception of Clint Eastwood (who would start the important part of his journey far from Hollywood) but the older stars still had box-office pull, for some part of the audience.

So we were given Westerns about the passing of the West, the last days of aging heroes. These Westerns continued to affirm the traditional values of the genre but acknowledged that the world might no longer need them, or if it did need them, no longer understand them.

The twilight Western really began with the last shot of John Ford’s The Searchers in 1956. Ethan Edwards, a somewhat deconstructed hero, walks off alone, having performed his last heroic deed — there is, at any rate, a suggestion that no more such deeds await him.

Ford continued the deconstruction of the Western hero, and offered a look at the times that made him irrelevant, in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence — a film told mostly in flashback. Budd Boetticher had previously made a series of brilliant films starring the aging Randolph Scott, still noble and implacable in virtue, but always alone — not just a lone wolf, like many Western heroes, but marked with a sadness for lost times. The Boetticher-Scott Westerns are uncompromising in their celebration of traditional values, but haunted, too, by a sense of something coming to an end . . . by the idea that Scott’s stoic hero may be the last of his breed.

This idea is made explicit in Sam Peckinpah’s first Western (and second feature), Ride the High Country, from 1962. Scott (above on the left) plays an aging hero who loses faith, at least for a while, in the code he has always lived by. Joel McCrea (above on the right), almost as old as Scott, holds on to that code, knowing full well that the world no longer gives it much credit, if it ever did.

The film is an elegy for and affirmation of this old code of

the Western hero — a combination that is both inspiring and poignant.

It’s a new kind of Western, too, in its treatment of its female lead, played by Mariette Hartley (above). She offers, as in many Westerns, an occasion for testing the gallantry, and thus the true worth, of the male characters, but Peckinpah makes an effort to get inside her head, to let us imagine what the test means for her. One can’t really call Peckinpah’s perspective feminist, but it’s a step in that direction.

Ride the High Country has taken on a deeper emotional significance over the years, since we now know that the end of the Western genre it seemed to sense was in fact just over the horizon. Curiously, the most successful revivals of the Western have gone back to the twilight theme — Lonesome Dove and Unforgiven, for example, have aging heroes out for one last adventure. It’s a pattern also followed in two modern-dress Westerns, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada and No Country For Old Men, both starring Tommy Lee Jones, of Lonesome Dove. The title of the Coen brothers’ film might have served as the title of Ride the High Country as well. Both films suggest that with the passing of the old men, some hope for the redemption of the new world coming into being has been lost.

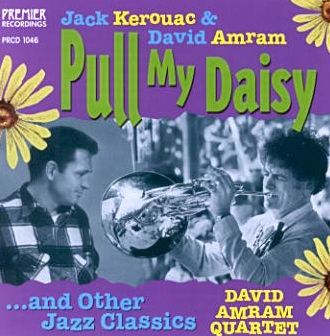

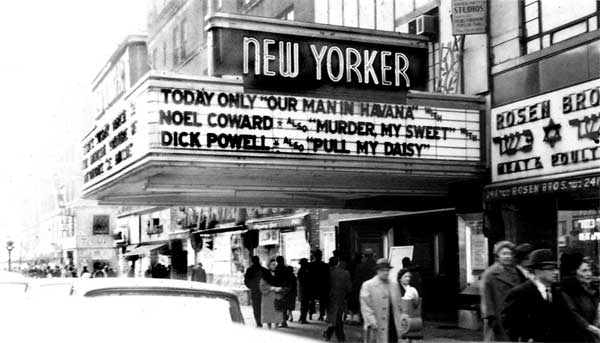

PULL MY DAISY

Paul Zahl (of this site's The Zahl File and his own marvelous PZ's Podcast) observes beats and a bishop cavorting on screen in a strange document of the Fifties:

SNAKE-DANCING BISHOP

Pull My Daisy, the 1959 “beatnik” movie by Robert Frank and Alfred

Leslie, with narration by Jack Kerouac and music by David Amram, has

one amazing character in it, unique, I'll bet, in American literature. The character is a Christian

bishop possessing, to put it mildly, wide-ranging interests.

Pull My Daisy is a casual treatment in film of Act Three of Kerouac's

1957 play entitled Beat Generation. The play was not produced. It

concerns some Lower Manhattan beatniks, played by Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Peter Orlovsky, and Larry Rivers, who receive a chaotic

visit from “The Bishop”, played by Mooney Peebles. During the visit,

the beatniks, especially Allen Ginsberg, try out their ideas on this

religious man, and variously try to tease him.

Here is Kerouac's narration of the Bishop's grilling:

“And Allen is saying, Is ignorance rippling up above the silver ladder

of Sherifian doves?

“(The Bishop) says, Yes yes yes, Sherifian doves, yes . . . In any case

we are not concerned one way or the other about what we're thinking about,

about anything in particular. But perhaps we sit in some kind of quiet

bliss. And he goes on trying to explain it because he really knows

what he's talking about.”

Later, the filmmakers, in a high reflective pause, somewhat lengthy,

show The Bishop leading the women and children of the beatniks in

prayer and song, all standing out in front of the Third Avenue loft

building where the visit is taking place. Kerouac voices this over:

“The angel of silence hath flown over all their heads.”

Towards the end of Pull My Daisy, The Bishop excuses himself in order

“that I go now and go make my holy offices (laughter): if you know what

I mean.”

But Wait! There's more on this Kerouacian Bishop.

We learn in Act One of Beat Generaton, on the third act of which Pull My Daisy is based, that The Bishop's denomination is “the new,

ah, Aramaean church.”

We also learn The Bishop is wonderfully weird. He says to the Allen

Ginsberg character, “We cannot expect solutions, or nirvana, eh, if you

wish to call it that, without making some eff-fort in the direction of

God, some movement (AND HE TWISTS)”

IRWIN (Allen Ginsberg): Ooh you twisted just like a snake then . . . Yes

your movement then was exactly like a supernatural illustrated serpent

arching its back to Heaven . . . I mean that was the hippest thing I've

seen you do tonight.”

The Bishop also praises the Kerouac character, whose name is “Buck”:

“You're making sense and you do drink (LAUGHTER)”

Our “Buck” has the last word on The Bishop:

“Bishop, let me say, you're positively right in everything you say and

you're a very sweet man.”

BISHOP: My disciple here!

Behold, then, dear Sisters and Brothers, a hip bishop, snake-dancing

with the beats over on Third Avenue. May his tribe increase.

A ROBERT MCGINNIS FOR TODAY

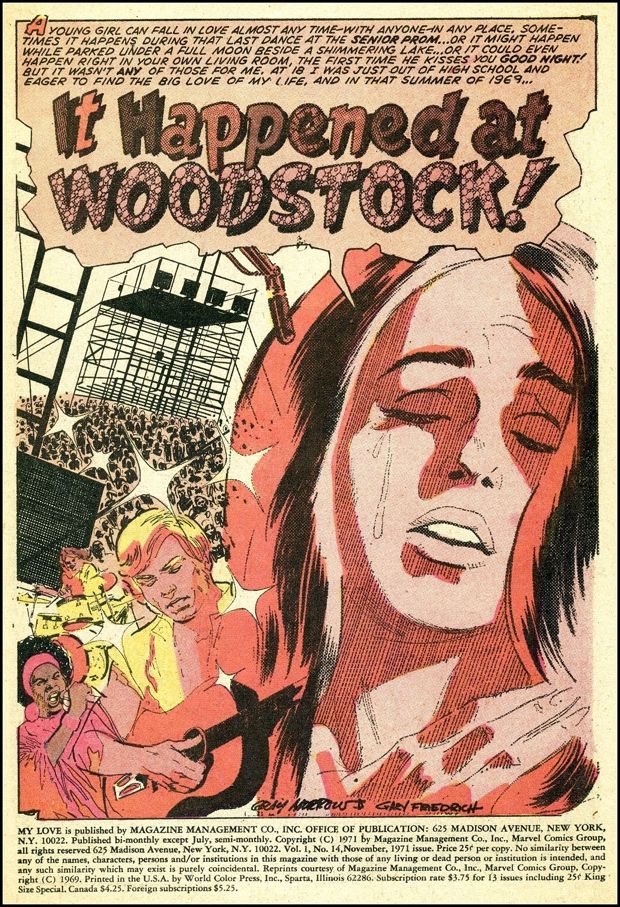

A COMIC BOOK PANEL FOR TODAY

We forget that large rock concerts are often occasions for shattering heartbreak . . .

ESSAY IN HONOR OF ANDRÉ BAZIN: PALPABLE SPACE

Follow this link for the eighth in a series of essays in honor of André Bazin . . .

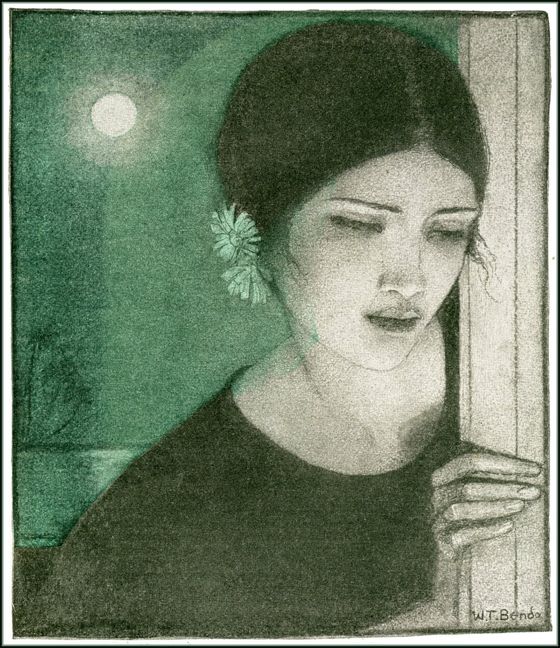

A BENDA FOR TODAY

A study in green by W. T. Benda, Polish-American artist and illustrator from the first half of the 20th Century. He later became more famous for making exquisite masks used in theatrical productions.

[With thanks, as so often, to Golden Age Comic Book Stories, the greatest web site known to humanity.]

AMERICA IN COLOR

Montana, August 1942. Some things don't change.

[Reproduction from

color slide. Photo by Russell Lee. Prints and Photographs Division,

Library of Congress]

A BÉRAUD FOR TODAY

Jean Béraud's portrait of remorse — but for what? Thus did the Victorians tease and titillate . . .

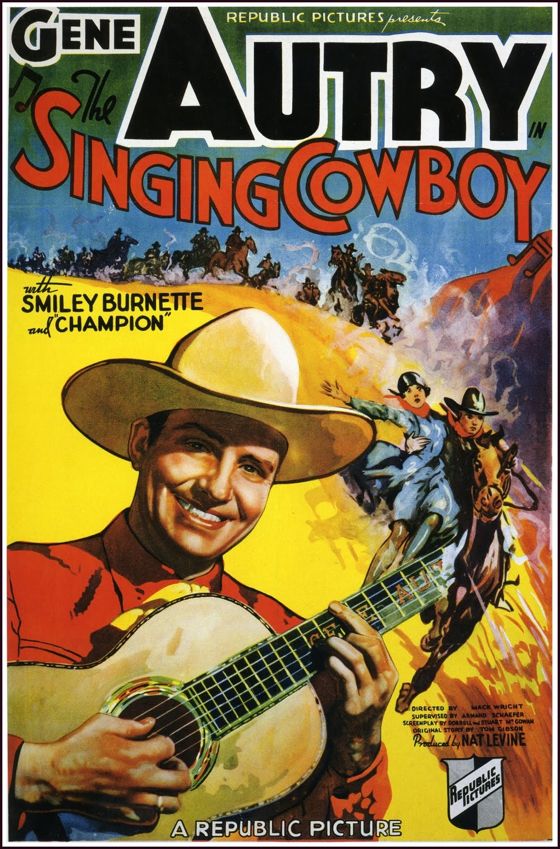

A WESTERN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

FROM THE ARCHIVES: REPORT FROM THE BEACH, 5 APRIL 1999

The advent of these bright, mild days of April means only one thing to

the Ventura resident whose soul burns for adventure — the

rollerblading season has begun.

The view from the back of a horse is one of antique magnificence, in

which honorable deeds seem inevitable and glory within mortal grasp.

The view from rollerblades is not quite so lofty, of course — but

still, how one towers over the ungainly tread of the joggers, with

their slightly embarrassed smiles distorted by anguish and despair.

On rollerblades your feet are winged, your spirit flies out ahead of you, and it's all you can do to keep up.

For the full report, go here: