I

personally like to hear a little religion come up in the political

discourse of this country. Abraham Lincoln, like Martin Luther

King after him, was very good at reminding us that our actions of the

moment have to be seen in the light of transcendent values, and

religion has powerful language in which to frame such ideas.

Here's Lincoln on the human cost of the Civil War (spoken at his Second Inaugural, above):

Fondly do we hope — fervently

do we pray — that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.

Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by

the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil

shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn by the lash

shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said

three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, “The

judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

Word up, dude.

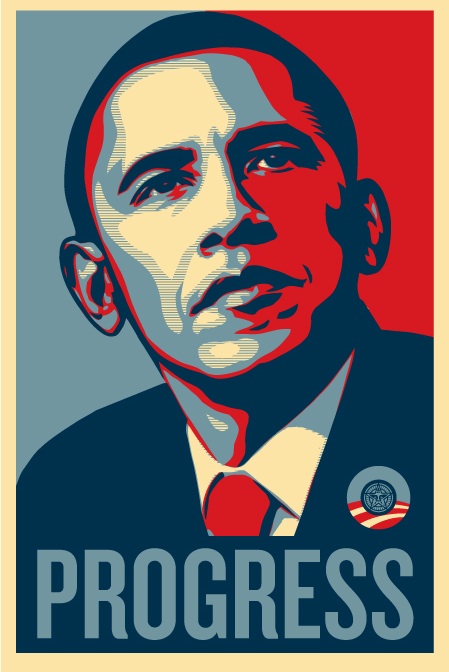

Barack Obama first got my attention in his speech at the 2004

Democratic Convention when he said, in the space of a few lines, “We've

got some good gay friends in the red states . . . and we worship a

righteous God in the blue states!” It occurred to me that no

other politician on the national scene could say both things with such

fervor and conviction. I'm sure that Hillary Clinton's faith and

John McCain's faith are sincere, but neither could use the phrase “a

righteous God” with such an unselfconscious sense of joy — and neither would dare to

speak with true affection for gays, afraid of alienating some

constituency or other, regardless of their stated positions on gay

rights.

I was really pissed off at the Mike Huckabee campaign ad in which a

bookcase behind him was lit to present the image of a gleaming

cross. Huckabee later said it was inadvertent. Right.

It was a Christmas message, in which Huckabee mentioned celebrating the

birth of Christ — why lie about the cross image? Was he just too

wimpy to put a crucifix behind him — did he think it would be better

to sneak it in? Subliminal messages like this, especially when

denied, are very

creepy. (Have a look at the ad yourself here and draw your own conclusions.) I also am totally unmoved by mere statements of faith, or

policies defended by scriptural doctrine. I want the ideas behind

those doctrines to take center stage in the discourse.

Michelle Obama, who is becoming a truly powerful speaker, said the other day

in California that “our souls are broken” in this country because we have lost some of

our capacity for empathy with “the least of

these”. She was using what is essentially a religious argument,

and referencing scripture in the process — these lines from Matthew:

Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.

That's

one of the most radical statements in the history of human thought, and

a keystone of Christian faith, but Mrs. Obama was using it in the

context of an argument about ideas — about the way a democracy ought

to function. She wasn't arguing about getting religion back into

public life, with symbols and slogans, she was getting religion back into public life by speaking to (and from) its wisdom.

You don't have to be religious to appreciate the value of religious

language for illuminating complex moral ideas — Lincoln's own

religious faith was a little murky even as he penned the words I've

quoted above. And even if you are religious, you can afford to be

offended when politicians use the language of faith as a marketing tool.