In the late 60s, just before or just after I dropped out of Stanford, a couple of friends and I decided it would be cool to drive down the entire length of the Baja peninsula to Cabo San Lucas. Cabo San Lucas wasn’t an international tourist destination back then, it was just a romantic name and point on the map — getting there seemed to promise high adventure.

We set off from the Bay Area in a banged-up but serviceable car one of my friends owned, camped out on a beach the first night somewhere between there and San Diego and crossed the border at Tijuana. We didn’t pause in Tijuana but headed straight for Ensenada because we’d heard there was a good beach there.

There was — we spent an entire day hanging out on it. The wind off the Pacific was fierce and disguised the fierceness of the sun. We were all horribly and painfully sunburned at the end of the excursion and so headed into the grubby little town of Ensenada for some

anesthetic treatment — cervezas, to be precise.

We quickly drank enough to take our minds off the sunburn — and apparently I drank even more than that. I’m told I had to be dragged back to the cheap motel room we’d rented because I kept accosting anyone who looked like an American and screaming “Hey, turista!” at them. I don’t remember this.

I do remember the motel room. We could only afford to rent one room and it had only two single beds in it, so one of us had to sleep on the floor. We flipped a coin and I lost. The hard linoleum of the floor instantly sobered me up, because there was no way to lie on it without reminding me of the sunburn — each new position shifted the searing pain to a new part of my body. It was a long night.

In those days the road to Cabo was not paved below Ensenada, but we assumed it would be a decent dirt highway. It wasn’t. At a gas station we asked a friendly local if it got any better further south. He said it didn’t, but didn’t get any worse, either. He did strongly advise us not to travel at night. “Why?” we asked. “Because of the bandits,” he replied, matter-of-factly, as though “the bandits” were a well-known hazard of travel in Baja California.

As it turned out, the road was a greater hazard. Less than halfway to Cabo we realized that the car’s shocks would never survive several hundred more miles on such a bad surface. We were losing heart.

We decided to camp for the night on a beach and take stock of the situation. It was a beautiful beach, and utterly, absolutely deserted — one could look for miles it seemed in either direction and see no other living soul. This was surreal but exciting, the stuff of romance. We woke in our sleeping bags at dawn the next day to low growling sounds moving closer and closer to us. They came from a large pack of wild dogs scavenging along the beach. They may have just been looking for food but they also had the air of creatures looking for trouble.

We hurried into the car and started north again. Things had simply gotten too romantic, and the idea of bandits didn’t seem so improbable anymore in the midst of such vast and awesome desolation.

There’s an o. k. paved road all the way down to Cabo now. Ordinary Americans travel it every day unmolested by bandits. Ensenada has become a trendy resort town, and Cabo is an outpost of high luxury.

Probably some of the wildness I remember is still there in Baja California, off the beaten track. I’m going back to look for it, anyway.

If our paths should happen to cross at a remote seaside cantina some night, just raise your glass and scream, “Hey, turista!”

Category Archives: Main Page

WATTEAU

The most erotic oil painting I ever saw — the only one that ever made me . . . tense (as my friend Kevin Jarre used to put it) — was by Jean-Antoine Watteau, the 18th-Century French painter. It was a small, uncelebrated work in a big show of Watteau’s paintings at the National Gallery in Washington in the 80s. It showed a half-clad women sitting on the edge of a bed, seen from behind. Its focus was on the line of her neck and back — the luminosity of her flesh drew one into the space of the painting as one might be drawn towards touching the woman.

Watteau was the poet of women’s backs and necks — of the half-clad female form. In his portraits of women it is always the inclination of the body which suggests a sexual, an erotic mood. What’s startling about his women is that they do not seem to be posing for men, but responding to inner passions — in a manner that is vexing but never teasing. Watteau’s whole world is invested with this delicate current of inward pleasure, of the small gestures, even in social gatherings, which resonate with sensuality, with foreshadowings of physical abandon.

There is no repression in this — just a kind of delicate, subtle foreplay. It has the aura of an exquisite, complicated game. It is theater — both preposterous and sublime. Watteau was interested in the theater, as well as in civilized flirtation, and seemed to see a link between them — but there is a great sadness in his theatrical paintings. His Italian Comedy players, his Pierrots and Harlequins, have a goofy kind of despair — tragic eyes. In this his vision achieves its grandeur and gravity — as he concedes that the sweetest things of life, than which there is nothing sweeter than the line of a woman’s throat, are mortal, will fade, will die, as passion expends itself in satisfaction.

What arouses one about Watteau’s portraits of women is what makes one grieve over them — what makes one see oneself in his bewildered stage lovers and suitors. He is a profound artist, sweet and thrilling and mournful all at once.

AN ELEGY FOR OYSTERS

. . . by the great Irish poet Seamus Heaney:

Alive and violated

They lay on their beds of ice:

Bivalves: the split bulb

And philandering sigh of ocean.

Millions of them ripped and shucked

and scattered.

We are eating oysters again, and will be until April, the last month with an r in it until next September . . . but we must remember that each of their alien, unfathomable lives is precious, not to be taken lightly.

THE TAKING OF CHRIST

Look at this image. Just look at it.

It was painted, in 1602, by Caravaggio — at least, that’s the current

wisdom. It was long thought to be a copy of a lost Caravaggio original

made by a follower or pupil, but in the 90s an art historian made a

convincing case for the attribution to the master himself.

Formally, it’s a dazzling work. The figures occupy a shallow space but

the picture still produces a strong impression of depth because of the

stereometric modelling of the light, the way the figures block and seem

to jostle each other even in the confined space and the way the centurion’s armor

jumps out at us like a physical assault. It has, finally, the plastic quality of a relief sculpture.

Caravaggio has placed himself among the dramatis personae here, as the

bearded figure on the right holding the lantern. This reinforces a

sense of the immediacy of the dramatic situation depicted, as

though it were an incident the artist himself witnessed and recorded

faithfully out of some urgent compulsion.

I personally would trade almost all the painting done in the 20th Century for this one work. Wouldn’t you?

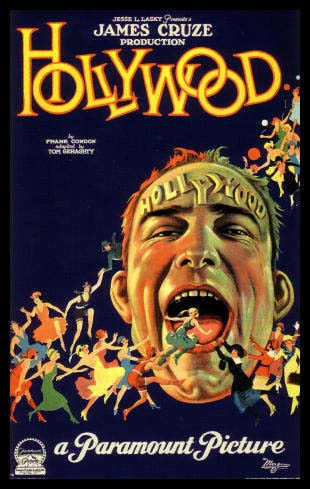

RADICAL AESTHETICS

Jean-Luc Godard has credited much of the impetus of the French New Wave to the fact that the young filmmakers who created the movement had spent so

much time watching silent movies, courtesy of Henri Langlois, the great

film collector and founder of the Cinematheque Francaise.

Godard believed that the radically alien aesthetic of silent movies allowed

these young filmmakers to see the medium with fresh eyes, freed from

the expectations of current style enforced by the habits and dictates

of the French national film industry and the Hollywood studio system.

Godard also said that the principal idea of the New Wave was to get everybody

out of filmmaking who didn’t belong in filmmaking — to wrest control

of the medium from corporate functionaries and state bureaucrats and

return it to those who actually created movies.

Today, when corporate control of popular movies is nearly absolute, and

forcing its range of possibility into narrower and narrower limits, a

study of silent cinema is even more likely to inspire the sort of

resistance that will be required to rescue movies from corporate

perversion and reclaim them for humane expression on behalf of the

culture at large.

D. W. Griffith once said, paraphrasing Joseph Conrad, “What I’m trying to do after all is make you see.”

Look.

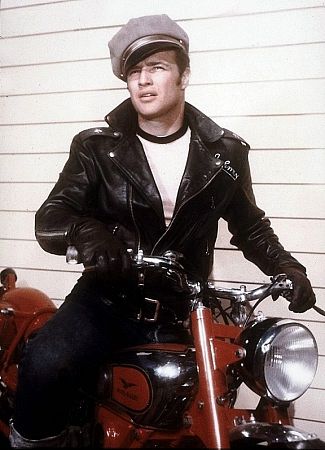

AMERICAN CLASSICS

Marlon Brando in “The Wild One”, 1954, wearing a Perfecto motorcycle jacket.

The jacket, originally manufactured by Irving Schott in 1928 and named

for his favorite cigar, was the first motorcycle jacket to feature

zippers. It’s still made by the Schott company, virtually unchanged

since Brando’s day, and is an iconic American classic, an almost

perfect thing. If you buy one, get the original stiff-leather version

and break it in yourself. There are soft-leather versions

available, but these are for pusillanimous yuppies.

When I wear mine I always think of “Johnny” — the coolest actor of my lifetime.

ROMANCE

Sorting through some old copies of The New Yorker from the 1980s I ran across this by Arlene Croce from one of her dance reviews:

“One hears so much about the death of romance in the relations between the

sexes that whenever an artist manages to make a truly romantic work one

has to ask where he got the material for it. Usually, the answer is

that he got it from the past — the artist has produced a study in

nostalgia. Changing sexual attitudes are imbued with a permanent sense

of loss. How can we really have lost something, though, and kept the

appetite for it? The appetite for romance and all that goes with it —

chivalry, the graces of courtship, the charm of intimacy — is in

itself romantic. So is the idea that we have lost romance.”

I would add that romance is in some ways about loss — it expresses a

fondness for all those things that will not last, for the flight of

time and the transience of the flesh . . . it embodies a kind of

respect and gratitude for the sweetness of life’s passing, in moments

of ecstasy and in the common rounds of everyday experience, and through

that respect and gratitude — all we can offer in the face of mortal

circumstances — it builds a monument of echoes, of faithfulness and

memory, that resists the ruthlessness of time.

I think of some lines from Robert Louis Stevenson’s poem Romance:

“And this shall be for music, when no one else is near,

“The fine song for singing, the rare song to hear,

“That only I remember, that only you admire,

“Of the broad road that stretches, and the roadside fire.”

SANTA TERROR

O. k., the drama of Christmas isn’t always gentle. This picture

is from a series of vintage photographs of children terrified by Santa,

mostly in his commercial incarnations in department stores, where the

true spirit of Christmas is routinely ground down into artificial snowflakes.

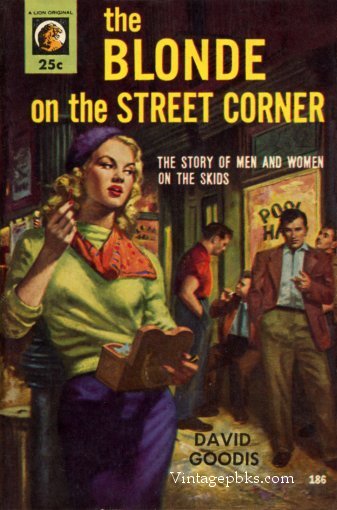

WHAT IS THIS?

What this is is an excruciating, bitter, brilliant example of pulp noir

fiction from the Fifties. Even though it’s set in the Thirties it

reflects the same post-WWII disillusionment that the Beat writers mined

— but it’s much tougher and starker, much less romantic and

pretentious than any Beat fiction. It makes William S. Burroughs look

like the James Branch Cabell of despair.

Many of Goodis’s pulp novels have been made into movies — Truffaut’s “Shoot

the Piano Player” was adapted from Goodis’s “Down There” — but not

this one. It’s just too grim, I guess, and its eroticism too perverse.

But its jagged broken-glass style and unflinching gaze are also

exhilarating.

[The cover above is from the original edition, but it’s still in print between less lurid wraps.]

EGG NOG

Is there a more congenial day in the whole year than the Friday after

Thanksgiving, when it becomes proper to begin celebrating Christmas?

There should still be lots of turkey left for sandwiches and soup, it

is permitted to play Christmas music incessantly, and the season of egg

nog begins.

A jigger of good Brandy in a glass of store-bought nog will do the

trick — and does for me every night of the Christmas holidays. Sipped

on a cold night by the fire, egg nog revives the calm and coziness of

childhood Christmases as the gentle suspense of the season built to the dramatic

revelations of Christmas morning.

Later in life one comes to appreciate that Christmas is a celebration

of childhood on every level, as much of the world pauses to honor

the birth of a child, a miracle revealed if only momentarily as a

mystical event, beyond comprehension . . . the very definition of joy.

Cheers!

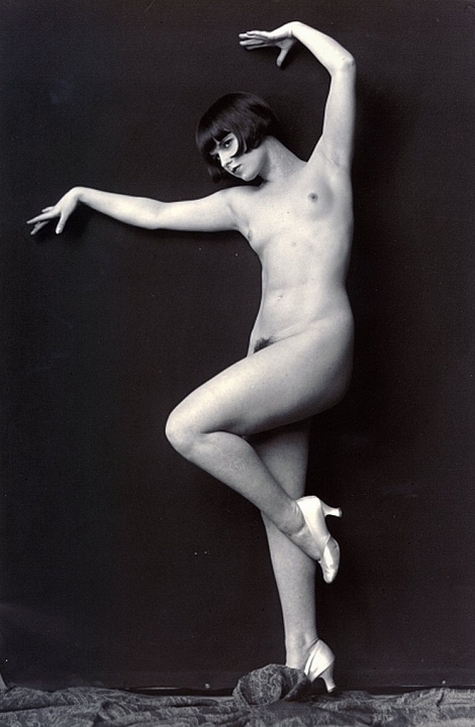

LOUISE BROOKS

2006 marks the 100th anniversary of Louise Brooks’s birth. It’s been

celebrated by the release of a cool new picture book about the star,

“Louise Brooks: Lulu Forever”, by Peter Cowie, and a special DVD

edition of her most famous film, “Pandora’s Box”, put out by Criterion,

with lots of extras.

Brooks was, like Garbo, a creature who had her being on film — her way

of moving through cinematic space could transcend the films that tried

to contain her, transcend the normal conventions of “screen acting”.

Early in her career she played second lead in a mediocre comedy called

“The Show Off”. She doesn’t seem to be part of the film at all — she

looks like someone who has wandered onto the set while the cameras were

rolling and decided to stay and observe the curious behavior of the

people around her. She appears to have found this behavior only

vaguely amusing, and in this delivers a wise critique of the film from

within the film itself. The effect is bizarre.

G. W. Pabst used her uncanny mixture of detachment and sensuality to

brilliant effect in “Pandora’s Box” — he was one of the few directors

who seems to have realized that a film had to defer to her phenomenal

screen persona or risk evaporating around her. It’s a film you should

watch at least once this year.

Happy birthday, Lulu.

MODERN TIMES

Bob Dylan’s new album “Modern Times” sounds as though it was made by people playing musical instruments, by a man singing with his voice, all in

some sort of space that might actually be encountered in the real

world. This is very unusual in modern popular music, and you might call

it revolutionary, even though it harks back to the sound of recorded

blues, rhythm & blues and rock & roll well into the 70s. (A

sign that the album’s title might be ironic is that its cover sports a

black-and-white photograph from the Forties.)

Beginning in the 70s, popular music began to take on what Theodor Adorno would have called a “phantasmagorical” quality — a process which he

explained in terms of the modern commodity culture, which tends to

produce objects which do not easily reveal how exactly they were made.

The commodity seller benefits from this because it obscures the fact

that he himself has not made the object he’s selling but appropriated

the labor of others to make it (perhaps unfairly.)

Adorno saw the same process at work in the music of Wagner, where a great wash of sound enchants us away from an appreciation of the fact that the

music is produced by individual musicians playing individual

instruments. (Stravinsky, who hated Wagner’s music, once wrote

passionately against the practice of listening to live music with one’s

eyes closed — he felt that one should never forget the physical

process of making music.)

R & b and rock sounded revolutionary in the Fifties quite apart from

their raucous beats and suggestive lyrics — they sounded revolutionary

because they sounded as though they were made by individual musicians,

not by workers in corporatized music factories. But with the rise of

disco and synthesizers and multi-track recording in the 70s, all fine

things in themselves, the recording industry had tools for resubmerging

individual performance into a corporatized “sound”. It commodified rock

and roll — made it phantasmagorical, in Adorno’s sense.

For some reason hard to fathom, “Modern Times” debuted at #1 on Billboard’s

charts and has been one of Dylan’s most successful albums ever. Perhaps

it’s attributable to the nostalgia of baby-boomers, hearing music that

takes them back to the golden age — perhaps it’s attributable to

younger listeners having their ears and minds opened up by something

that sounds different, new.

Most likely it’s a combination of the two — part of the old rascal Dylan’s strange alchemy whereby old forms and old language are somehow deconstructed and recombined to reflect the peculiar aura of the present moment.

TOURNAMENTS

My friend Jae has been in town recently, visiting from Brooklyn, and

we’ve been on a mini poker marathon. Neither of us had been doing too

well until we discovered a cool little no-limit Hold-’em tournament at

the Fiesta in North Las Vegas, held nightly at midnight. The card room

at the Fiesta is one of the last places in Vegas which allows smoking

around the clock, which means that it attracts a better sort of player,

cheerful, tolerant, democratic in a style you don’t find much in

American society today outside of casinos.

There are usually about thirty players who sign up for the tournament,

many of them regulars. The buy-in is $25, with an optional $10 re-buy

at the break. We’ve played it four times now — each time Jae has made

the final table but never cashed until last night, when he went out in

4th place and got his buy-in back. (Only the last three players are

guaranteed prize money, but when it gets down to the final four there’s

a tradition of voting to reimburse the buy-in of the player who goes

out in 4th — which has the effect of speeding up the game at a stage

when everbody is playing super tight to avoid finishing one out of the

money.)

On the first three nights I busted out about halfway through the

tournament but last night I made the final table with Jae — was chip

leader at about 3am when my two tablemates urged that we split the

potential prize money three ways then and there so they could go home

and get some sleep. I agreed reluctantly, but they were nice guys and

it seemed like the friendly thing to do.

I won $218 as my share of the prize money, my best take ever at a poker

session. I got amazingly good cards all through the tournament, and

one miracle river card when I was close to all-in, but I played the

cards well and didn’t make any calamitous boneheaded blunders.

It was a sweet night.

HELLHOUNDS ON MY TRAIL

In the wake of the Nevada smoking ban I feel a bit like Nathan Bedford

Forrest after the surrender of the Confederate armies in 1865. Riding

along with a companion, Forrest reached a crossroads. “Which way?” his

companion asked. “Sir,” said Forrest, “if that road led to Mexico and

the other to Hell, I wouldn’t much care which one I took.”

Since I also feel that there are hounds from Hell on my trail, sick, vicious

duppies driving me from home to home, refuge to refuge, I’m inclined to

think that Mexico might be the better of Forrest’s alternatives. It’s

where Americans have often gone to lick their wounds and get their

bearings again after the world collapsed around them.

I find my spirit drawn to the ocean as well, “la mer toujours recommencee”,

always recommencing, obliterating time with each new wave, like a new

deal of the cards. Wanting a romantic landscape, too, and a relative

absence of American tourists, my mind drifts to the Mar de Cortes, the

Sea of Cortez, also called the Gulf Of California, that legendary sea

between the Baja peninsula and the Mexican mainland.

There is a town there called La Paz, with a seaside promenade and palapa huts

serving fresh fish tacos and Tecate beer, a port town from which the

Mar de Cortes can be explored and fished in a small open panga boat.

The land behind it is severe and mystical desert, the sea before it is

teeming with marine life of every description, much of it good to eat .

. . clams and oysters and octopi and shrimp, lobsters and tuna and

skipjack and crab.

Maybe I’ll see you there one of these days . . .