Category Archives: Music

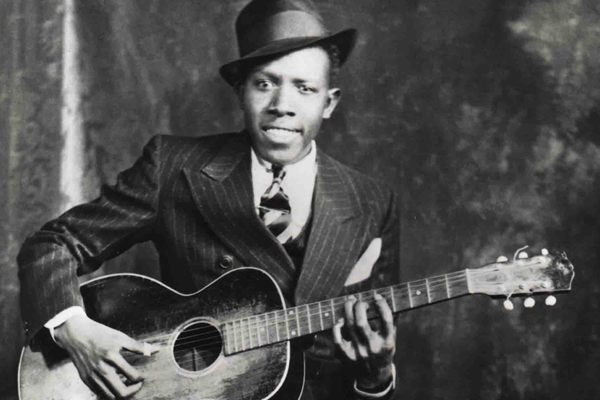

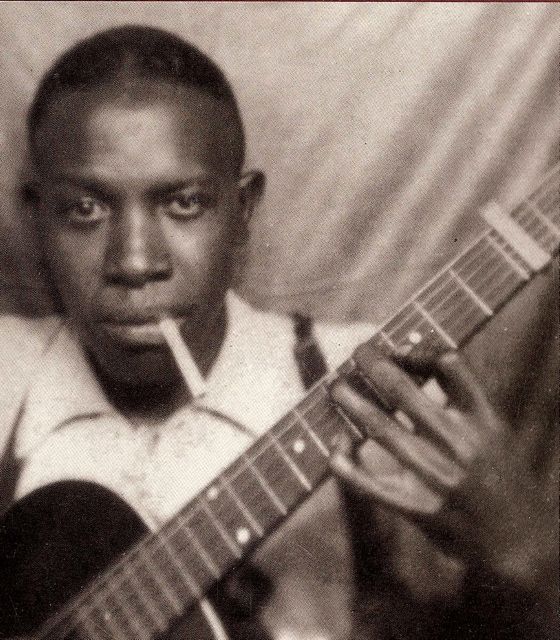

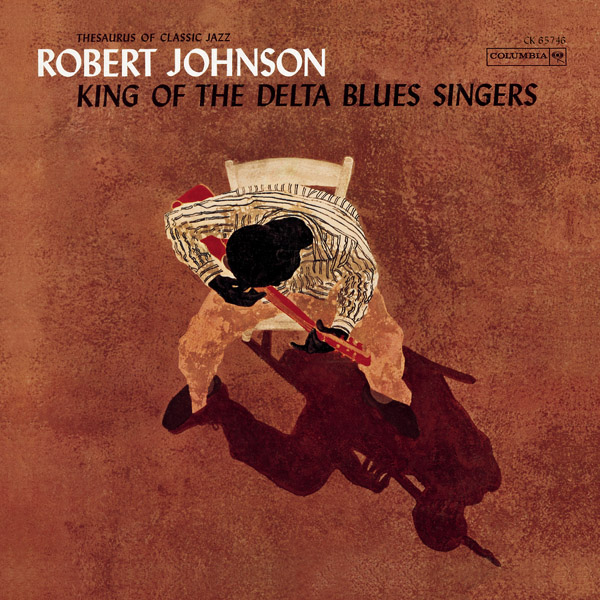

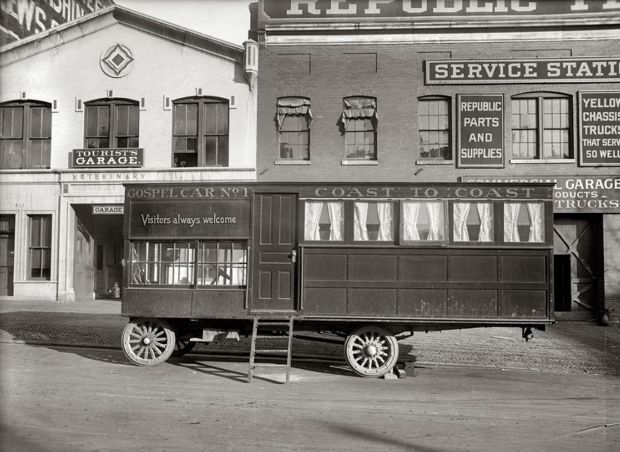

ROBERT JOHNSON CENTENNIAL

In honor of the centennial of Robert Johnson's birth this past May, Sony issued an amazing set of his works, on vinyl. Twelve ten-inch discs — the size of 78s but playing at 45rpm to accommodate modern equipment — reproduce all twelve of his records as originally released, twenty-four songs in all, complete with reproductions of the record labels.

The discs are packaged in a vintage-style 78 album — from which term we get the still-current designation for a single-disc LP or CD. The album comes with a CD of the new re-masters of Johnson's complete works (including the five outtakes not released on 78), a CD of related music and a DVD biography of the legendary bluesman.

I'm sorry that the set is so expensive — making it a kind of fetish object for Johnson worshipers, rather than the sort of thing that should be a part of every civilized American home, like a leather-bound set of the complete works of Shakespeare or Dickens, like a fine edition of The Bible. Johnson's work belongs in that company — as some of the greatest art ever produced in this country . . . as art that has helped define this country.

I went mad and bought it despite the price, and haven't regretted it. Pulling those discs out of sleeves and playing them on a turntable, just as they were originally made to be played, is a profound experience. This is partly due to the thrilling immediacy of the new re-masters, from which the commemorative vinyl was created. It may sound a bit processed to some ears, but there's no denying the startling presence of Johnson's voice and guitar, with all but the most minimal noise from the ancient discs eliminated.

It's partly due to the ritual of spinning the music on a turntable, putting you in touch with the earlier generations who first heard Johnson's music that way — the relatively few people who bought the original 78s, the musicians of the late Sixties and early Seventies, like Bob Dylan and Eric Clapton, who heard and were deeply influenced by the LP reissues.

Things are bad in America right now, politically, socially and economically. But anyone who's tempted to give up on the republic only needs to listen to the music of Robert Johnson to believe in America again. It's the best of what we have been — the best of what we might still be again.

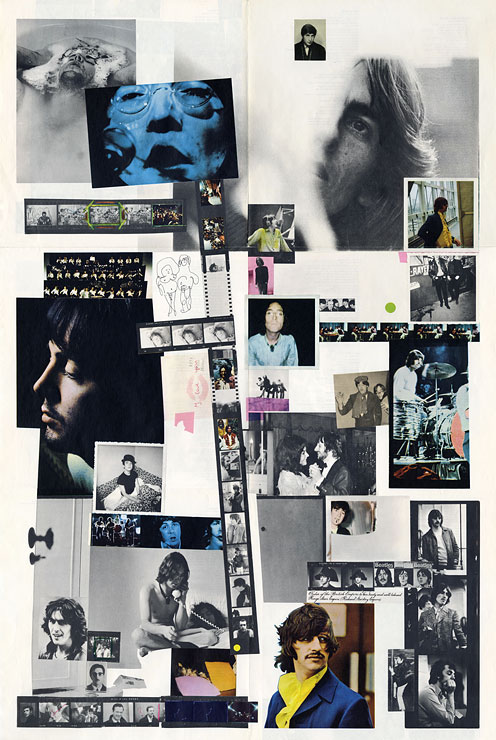

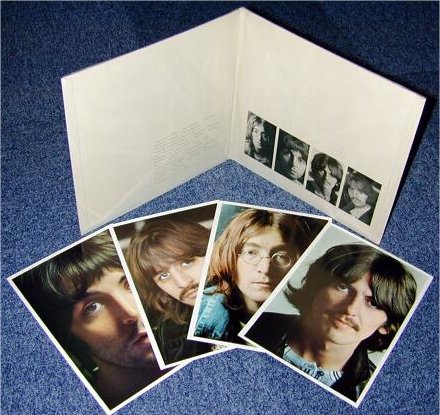

THE WHITE ALBUM

Let me put my cards on the table right up front — I don't think The Beatles (commonly known as The White Album) is very good. It's the weakest album The Beatles ever released — and even though that might mean it's better than the best album many goods groups have put out, that isn't much of a consolation. The Beatles have to be judged by their own standards, and by those standards, The Beatles is second-rate.

It's a fun album, to be sure — the songs are (for the most part) arranged and played and recorded with The Beatles' customary professionalism and musical inventiveness. The problem is the songwriting. The two-disc set is padded out with too many ditties that seem half-finished, tossed-off. They might be parts of great songs, or the germs of great songs, but as they stand they aren't even particularly good songs. Compare what the lads did with a similar batch of half-baked numbers on the second side of Abbey Road — turning them into a delightful musical montage that had a surreal unity of its own, like a deranged operetta.

At the time of The White Album Lennon and McCartney were basically writing (and sometimes recording) their songs separately. When each was firing on all cylinders, each could create magic — a Strawberry Fields or a Hey, Jude. At other times, though, the absence of the old synergy, when they were collaborating more closely, is keenly felt. Lennon's tendency towards more abstract imagery often resulted in self-indulgent incoherence — McCartney's tendency towards simple, sweet melodies often resulted in self-indulgent blandness. Both frequently found their way into the realm of banality.

I won't go through the misfires track by track, I'll just offer my idea of the best one-disc album that could be extracted from The Beatles. (George Martin himself begged them to extract a single-disc album from the material they'd recorded, so my idea isn't totally perverse.) I've had to add two songs recorded during or around the time of the sessions for The Beatles, out of concerns for length and quality:

“Back in the U.S.S.R.”

“While My Guitar Gently Weeps”

“Piggies”

“Why Don't We Do It in the Road?”

“I Will”

“Julia”

“Hey, Jude”

“Birthday”

“Long, Long, Long”

“Helter Skelter”

“Revolution 1”

“Savoy Truffle”

“Lady Madonna”

“Good Night”

You'll note that I've kept all of Harrison's songs — which were of a uniformly high quality. Not up to the standards of Lennon and McCartney at their best, perhaps, but well and earnestly crafted.

I've included a couple of Paul's silly pastiches, because that's where his head was at at the time, and they're good enough, for what they are. I've left off one of his better songs, “Blackbird”, because I don't think the arrangement of the released version really serves it adequately.

I've shortchanged Lennon, certainly, but the songs of his I've omitted are substandard variations on ideas he executed better elsewhere.

Ringo's “Don't Pass Me By” is a song best forgotten, but he's represented by his sweet vocal on “Good Night”, with its endearing whispered coda, which is one of the great Beatles moments.

Program your CD or MP3 player to reproduce the track-list above and see what you think.

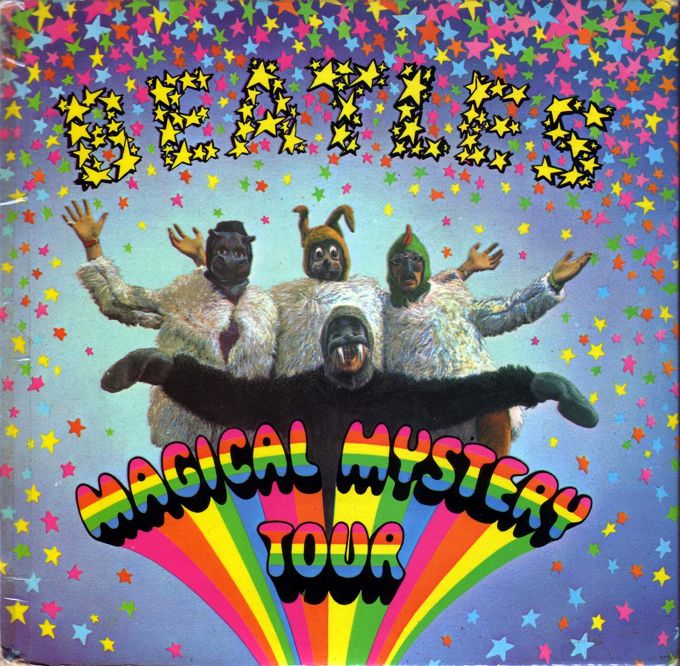

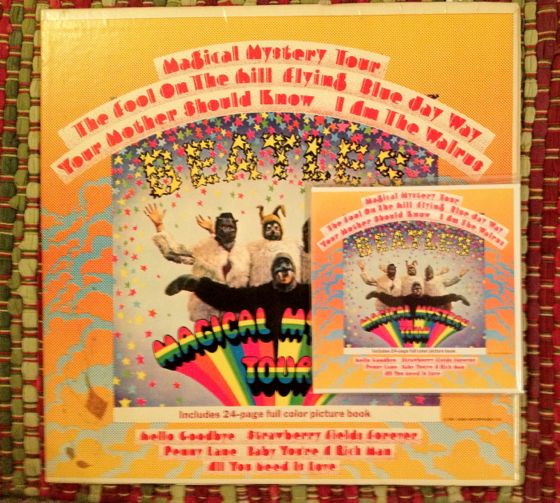

ROLL UP!

THE MYSTERIES OF VINYL

I recently got a new turntable — I'd been without a functioning one for

about 25 years, long enough, I reckon, to give me some perspective on

the experience of spinning vinyl.

I've heard people say that you can't really appreciate the superiority

of vinyl sound over CD sound except on audiophile equipment, but it's not

true. I have a decidedly non-audiophile music system and if I listen to a CD

after playing a couple of records I notice a difference immediately.

The CD sounds thinner, especially on the high end of the sonic range.

The ability to transmit the high end of a recording in warm, round tones

is what vinyl does best. And all across the sonic range it imparts a

presence to the music that a CD just can't.

CD mastering has improved dramatically in recent years. You can hear

the improvement best by comparing the first CD versions of the Beatles

albums with the new remasters. With the remastered CDs there's a marked

difference in the roundness and warmth of the tone. They almost sound

like vinyl — but not quite . . . and again it's in the high end of the

range that you notice the difference most clearly. When John and Paul

hit their high notes, their voices take on a slightly freeze-dried

quality.

The other aspect of spinning vinyl has to do, of course, with the ritual

of the thing. Pulling a record out of its sleeve, cleaning it, being

careful to set the needle down on it without harming either the needle

or the disc, getting up to flip the record over when one side is done —

these things put you in a certain specific state of mind. It conditions you to think of the disc as a precious object, and the music you're going to listen as special — an event.

I adore the convenience of having tons of music on my computer and

portable devices. It allows me to listen to more music, and more varied

music, than I otherwise would. (Twenty-four hours worth of Christmas music is still not quite enough for me.) But spinning vinyl encourages me to

listen to music more selectively and carefully than I otherwise would.

I'd never go back to black exclusively, but I also don't ever want to be without it again.

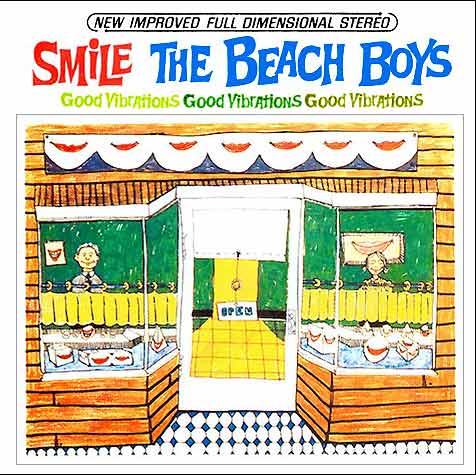

SMiLE

In re what's left of SMiLE, Brian Wilson's abandoned recording project for The Beach Boys from 1966-67, we stipulate to the following:

1) It is conceptually incoherent, at least from a rational point of view. It is probably not conceptually incoherent because it was abandoned before completion — it was probably abandoned before completion because it had no conceptual structure. Such a work could not by definition ever be completed. Wilson was working with some fuzzy ideas about what he wanted the album to be, but proceeded largely by feel.

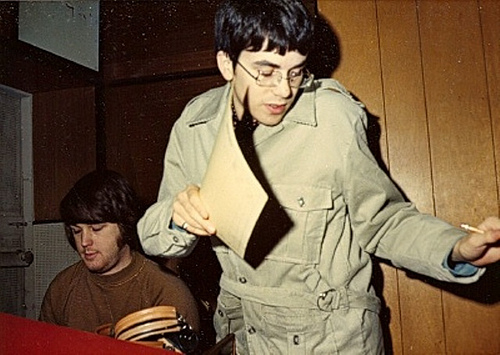

2) The lyrics, mostly by Van Dyke Parks (above), are uneven. Some are brilliant, some are overly precious, some are embarrassing.

But we find, after careful listening, that the following propositions are also true:

1) SMiLE is a great work of art, a masterpiece, and like nothing else in the history of American music . . . well, since Charles Ives, anyway. In Ives's work, Holiday Symphony, for example, Wilson could have found a workable intellectual rationale for what he was doing — a kind of collage strategy, with discrete passages of music connected to each other by the associations of memory (as well as the whims and tastes of the composer.) For all the musical influences coursing through SMiLE, though, I doubt if Wilson listened much to Ives, whose intellectuality and dissonance would not have appealed to him.

2) There is a coherence to SMiLE which derives from the sheer beauty and audacity of the music, and the logic of Wilson's own ear — the clear, utterly sensible flow of Wilson's joy in music, of every kind, from hymns to doo-wop. It's all unified further by the magical harmonies Wilson conceived for the voices of The Beach Boys. He recorded the vocal parts over and over again, trying to get the transcendent effect he was after — that little bit of magic beyond the sweet sounds that would constitute a proper musical offering . . . to God, as he saw it. He wanted SMiLE to be a musical offering to God.

3) SMiLE is a musical offering to God, of the best Wilson felt was inside himself. He wanted it to be more than he could realize at the time, but it's enough, as it is — a worthy offering.

4) Because the music is modular, built of passages connected to each other mostly by feel and intuition, it's possible to listen to the studio outtakes with the same pleasure and sense of discovery one has when listening to the reconstruction of the proposed whole. The musical passages are brilliant tesserae that can be combined into any number of mosaic patterns — each of which offers a different and wondrous new image.

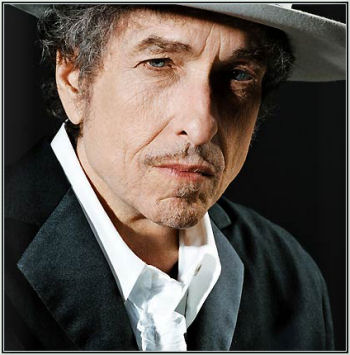

BOB DYLAN

Bob Dylan turns seventy today.

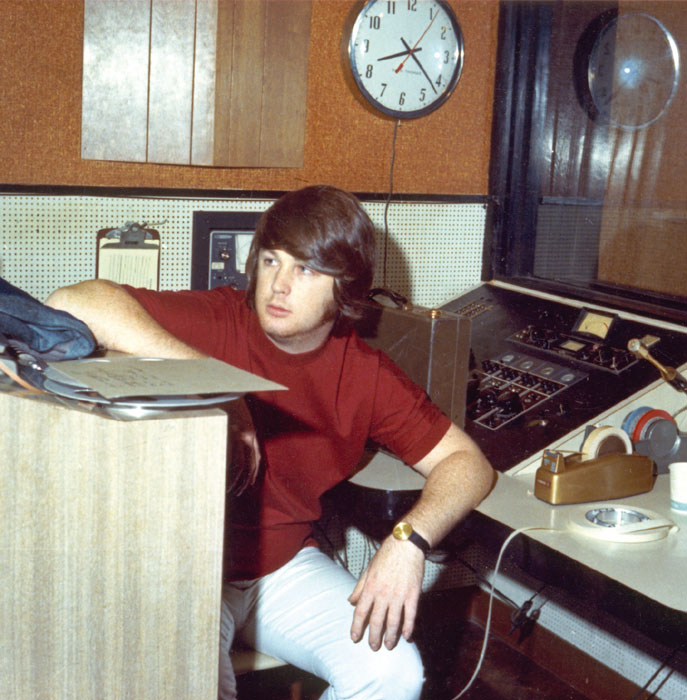

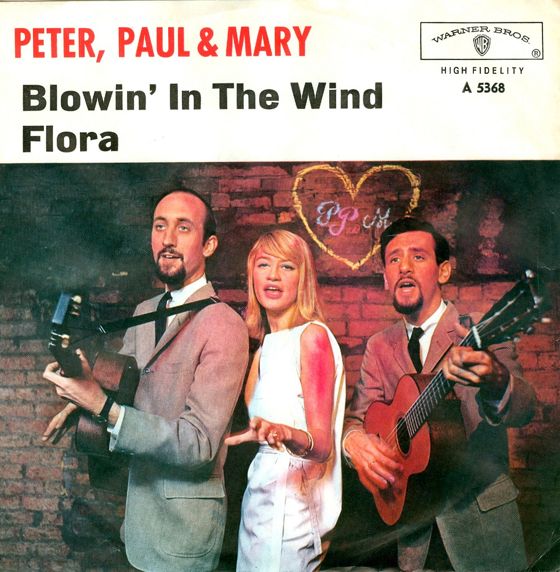

I first heard a Bob Dylan song in the summer of 1963, when I was 13.

It was Peter, Paul and Mary's cover of “Blowin' In the Wind”. Just

about everybody heard that version of the song in the summer of 1963 —

it made it to number 2 on the Billboard charts and got lots of radio

play.

In the Fall of that year I went off to boarding school and a classmate

had brought with him an LP of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. That was the

first Dylan album I ever heard.

So from the onset of puberty until today, Bob Dylan has been with me. He helped me grow up when I was a teenager, he helped me get

old. He helped me with belief and with unbelief.

Most of all he helped me with the problem of losing things. All of

life is about losing things — loves, innocence, friends, dreams. In

the end, we lose everything, in that pine box for all eternity. And

this is cool — it's what we're here to do. Lose. “The stars are

threshed, as souls are threshed from their husks,” is how William Blake

put it. Dylan said, “Just when you think you've lost everything, you

find out you can always lose a little more.”

The world, especially the modern world, tells us we can have

everything. In truth, we can have nothing, except what's left when

we've lost everything. Dylan sings about what that is, too.

Prophet, wise counselor, mentor, heckler, song and dance man — Bob Dylan has walked beside me every

step of the way through my adult life. Even when I lost sight of

him, he kept up with me, and was there when I needed him. Even when I gave up on him, he never gave up on me. “You might need this song someday,” he's always said, “so here it is.”

I know he would not want any thanks for this — the gifts he had to

give weren't his. He found them somewhere, and passed them along. He

never got adjusted to this world, and has reminded me that I shouldn't

get adjusted to it either. We've got business elsewhere.

SOHO

Remember the mornings I kissed you goodnight . . .

My friend J. B. White composed this song for a script I wrote in the early 1980s, about Soho, when that part of Manhattan was just coming into its own as a Bohemian enclave, and where I had so many magical adventures. Thirty years later, none of that Soho remains — it's a Yuppie shopping mall today — though the ghosts, the faces in the windows, are still there, I suppose, my own among them.

The places you

love that you can never return to are also places you can never

leave. They become part of your own small portion of eternity.

[Song © J. B. White]

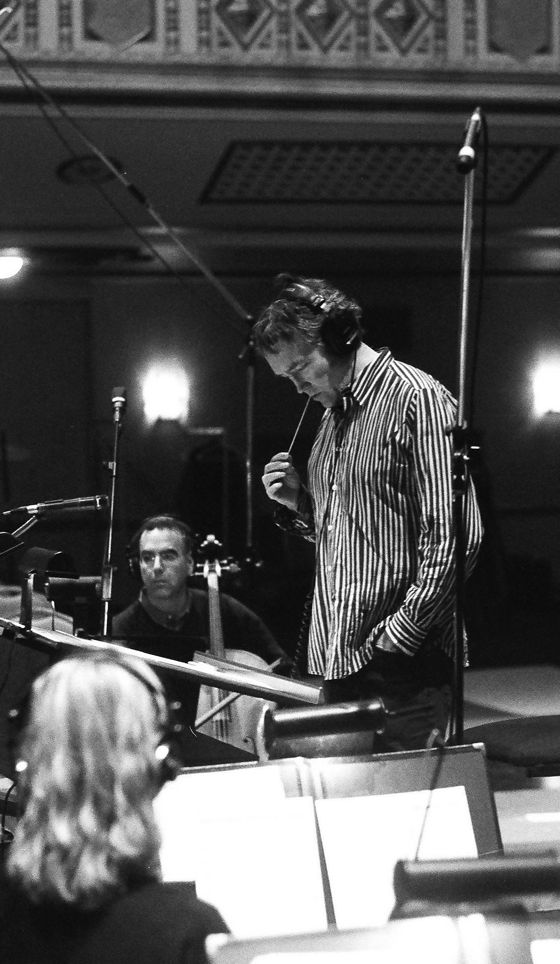

TRUE MUSIC

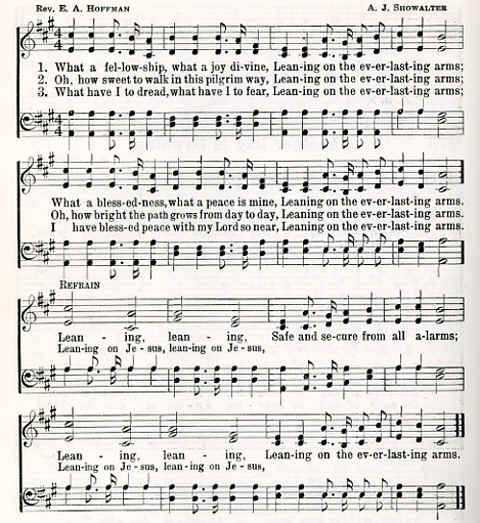

Carter Burwell's score for the Coen brothers' True Grit is one of the finest of recent times — a score inseparable from the film's emotional impact and moral meaning. It's therefore ironic, and actually insane, that it was deemed ineligible for an Academy Award for best score, because it is largely based on themes from old hymns.

From the time of Bach to the time of Bob Dylan, putting old tunes to new uses has been an important part of the work of many great composers. It is, paradoxically, an endeavor in which a composer can most clearly demonstrate his or her originality. Presenting familiar melodies to us in ways that renew them, allow us to hear them in new ways, requires a high degree of imaginative skill.

In his score for True Grit, Burwell works with hymns that are hardly central to the culture these days, but still linger in the collective memory. He rings variations on their melodies that are intimately tied to the moods and themes of the film, and link the film to the musical heritage of America, as the film itself is rooted in the history of the nation and echoes the history of the Western film genre.

Burwell's elegant arrangements don't trade in nostalgia, however, but evoke the severe and demanding faith of 19th-century America — the faith of the film's central character, Mattie Ross. They evoke the grandeur and the dignity of virtue and aspiration, not the narcosis of religious “comfort”. They harken back, as the film does, to what Greil Marcus calls “the weird old America” — the funky, scary, endlessly strange America of a relentless, antic, eccentric people who dreamed majestic things and then cobbled them into existence by any means that came to hand.

Burwell's arrangements have the flavor of the parish hall, of music made communally — simple and unadorned, but inexorable. There is no hint of pastiche about them, or of antiquarian reconstruction — they channel the pure spirit of the frontier.

“Leaning On the Everlasting Arms” is the central hymn in the score — it is associated with the “father theme” of the film. We hear it played on a piano over the opening shot of Mattie's murdered father, and then in moments when Rooster Cogburn and Ranger La Boeuf make emotional connections with Mattie, becoming the substitute fathers she so desperately needs. This is an unspoken theme of the book and the movie — speaking it out loud would have turned True Grit into a Disney film, but speaking it in music offers a subliminal and potent emotional reinforcement.

Wisely, Burwell doesn't use “Leaning On the Everlasting Arms” for the climactic set-pieces of the film — he switches gears to strike a bigger and more decisive note. When Rooster rescues Mattie from the snake pit, Burwell uses the melody of “Hold On To God's Unchanging Hand”, which we've heard once before in Mattie's great moment of heroism when she swims Little Blackie across the river, and first earns Rooster's admiration (although he admits to admiration only for her horse.)

The orchestration in the river crossing scene

is grand and noble, almost stately. It does not try to sell the excitement

and danger and suspense of what Mattie is doing, but to emphasize the

magnificence of her courage. It seems to summon up the whole epic sweep

of America's westward progress, and the thrill of every river crossing

in the history of Westerns. It's music that orients us morally to the

scene it's accompanying.

Using the theme again in the snake pit scene reminds us that Rooster's heroism there is on some level a response to Mattie's heroism — an attempt to honor it.

Film scores, especially today, don't often provide this sort of complex resonance with a film's themes — they usually just underline the immediate sensations of the scene in front of us. Burwell is collaborating with the Coens on a profound level here — making the score a participant in the construction of the meaning of the film. It's a stunning achievement, and the Academy has disgraced itself by failing to appreciate it.

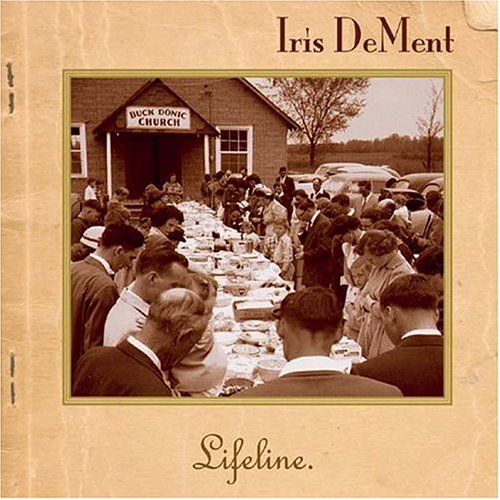

Burwell or the Coens made an inspired choice by playing Iris Dement's recording of “Leaning On the Everlasting Arms” at the film's close. Her performance is very powerful, accompanied by a simple piano and guitar arrangement. Her vocal is both raw, down-home, and beautiful, soaring — she seems to be singing to us from the heart of the 19th Century.

The score is a fine one to listen to on its own, but for some reason the soundtrack CD doesn't include the Dement recording. It's included as a bonus if you buy the album on iTunes, but only in the abridged version used in the film itself. For the full recording, it's worth tracking down Dement's album of sacred songs, Lifeline, which also features a sublime version of “Near the Cross”.

In her liner notes for Lifeline, Dement says, “These songs aren't about religion. At least to me they aren't. They're about something bigger than that.” The same might be said of the hymn tunes Burwell has adapted so brilliantly in his True Grit score. They resonate on many different levels at once, as the music for any great film score does.

COOL MUSIC VIDEO

. . . directed and animated by Kendra Elliott — an amazing piece of work.

Check it out here:

“Twilight Lovebite” by Lavalier

TIME FOR CHRISTMAS IN THE HEART

Let it spin, let it spin, let it spin!

DEBBIE HARRY

The tide is high but I'm holding on . . .

LONG BEFORE I KNEW YOU

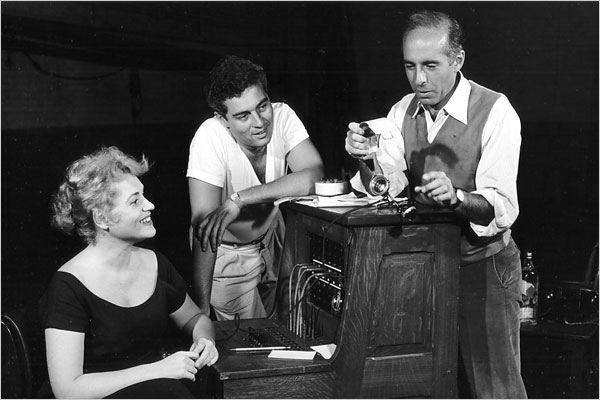

Found on the original cast recording of Bells Are Ringing, this is one of the loveliest ballads ever written for a Broadway musical. The fact that Judy Holliday and Sydney Chaplin had to strain a bit to hit their notes only adds to the poignancy of their performances. Unaccountably, and to me disastrously, the song was left out of the movie version of the show.

Above, Holliday and Chaplin with director Jerome Robbins during rehearsals.

PROMISES, PROMISES

My friends Mary and Paul Zahl made a lightning raid on New York City recently (from Florida!) to see the Broadway revival of Promises, Promises. Here is Paul's report on the show:

LITTLE NOT BIG, THEREFORE BIG

I think critics make a mistake when they bring ideology to a production

of the theater. In the case of the new revival of the 1968 musical Promises, Promises

by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, with book by Neil Simon, a lot of

ideology has flowed out on paper. A lot of energy has flown, for

example to the performance of Sean Hayes, the lead actor, and whether

a gay actor can portray a non-gay hero.

Energy has also flown to the attitudes, within the story, concerning

relationships in the work place between men and women, attitudes that

are supposedly typical of the 1950s and early 1960s and no longer of

today. (The musical was written and first performed in 1968, although

it is closely based on Billy Wilder's 1960 film The Apartment, which he co-wrote with I. A. L. Diamond.)

As I say, a lot of present-day ideology has become involved in the

critical reception of this Broadway revival of Promises, Promises. No

matter that, however, Variety reports that Promises, Promises is a

commercial success. The weeknight performance my wife Mary and I

recently attended was sold out, not one empty seat; and the audience

was overwhelmingly appreciative, interrupting the show frequently and

offering the cast a long standing ovation at the end.

For myself, Promises, Promises is a little story, about a “little guy”

who wins the girl — because he really loves her and doesn't use her —

and therefore a big story. In drama, so goes my notion, when a

personal story is well and compassionately told, that story becomes a

big story. On the other hand, attempting to weight a personal story

with ideology, especially pre-conceived ideology, diminishes the

attempt.

Promises, Promises narrates the disillusionment of a “little guy” at

Consolidated Life, whose crush on a “little” fellow employee turns out

to be a crush on the mistress of his married boss. C. C. Baxter's sweet

and selfless crush on his “angel in the centerfold” ( reluctant

mistress to the unscrupulous Mr. Sheldrake) is crushed in the first

act, and on Christmas Eve! However, when Miss Kubelik tries to commit

suicide out of her own disillusionment with Sheldrake — after a sorry

tryst in C. C.'s apartment — things both fall apart and come together.

Baxter shows real love for his true love, who seems hopelessly and all

the time in love with another man. With the merciful intervention of a

kind and honest doctor who lives next door, together with C. C.'s urgent

rising to the occasion of her overdose, Miss Kubelik rises from the

dead, or the near dead.

This love from a real and kind man, C. C.

Baxter, as compared with the cynicism and selfishness of boss

Sheldrake, touches her, and finally wins her heart. The curtain “clinch” is credible, unsentimental, and very, very touching. It is

made even more credible by the reprise, this time with a positive

vibe, of Bacharach and David's famous song “I'll Never Fall in Love

Again”.

Why does the audience cry at the end? Why was the applause sustained

and very loud? Why did the people leave moved, and happy? I think

it's because the love of C. C. Baxter and Fran Kubelik is a universal

story enacted within a particular case. C. C. wins Fran. He saves her

life, both physically and emotionally; and at the very moment when her

long, passionate, hopeless affair with Sheldrake is exposed — at the

very moment! This is a little story about little people. It is

therefore big. Why? Because it's about everybody. Everybody knows

about the little guy. Almost everybody, male and female, is now or has

at some point been the little guy. It comes with being born.

There are a lot of theatrical touches to Promises, Promises that are

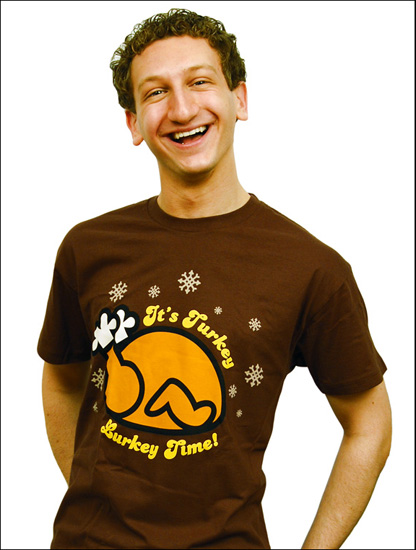

worthy of comment. The notorious Christmas Party song entitled “Turkey

Lurkey Time” is a number people seem either to hate or love. Mary and

I happen to love it. I think we could say we LOVE it. “Turkey

Lurkey Time” is just so unusual. Is it about men being turkeys? Mary

thinks so. Is it about the Christmas turkey, soon to lose his head?

Well, yes. Is it a song about the sheer euphoria of Christmas revelry

and drunkenness? Yes, too. Is it a smashing production number with

great ensemble dancing and an unpredictable finish? Yes, that, too.

Anyway, “Turkey Lurkey Time” has to be seen and heard to be believed;

and I, for one, am still singing it. (I made a mistake in the lobby at

the end, as we were leaving the theater. I was too cheap to buy the T-shirt of “Turkey Lurkey Time”, with snowflakes against a brown

background. Heaven: and I missed it.)

Then there is the unexpected moment of compassion for the “villain”,

J. D. Sheldrake. He sings a song entitled “Wanting Things”, about his

compulsion for wanting things he cannot have. The subject of the song

is what theology calls “concupiscence”. As he tolls his confession,

shadows of the several women in his life, all in scarlet but

half-hidden by the lighting, approach him, then slowly walk away, and

vanish. The number is haunting, and also even-handed. No person is

completely a villain.

The producers of Promises, Promises have added two songs from the

Bacharach-David repertoire to their revival of the show. One of them,

“A House Is Not a Home”, has to be one of the great American pop

songs. Both lead characters, Fran and Chuck (C. C.), sing it in

separate contexts, at different points in the narrative. It is almost

unbearably affecting. The actress Katie Finneran (above) also has a star turn

as Marge MacDougall, the woman Chuck picks up in a bar on Christmas

Eve just after he has learned the truth about Fran's affair with

Sheldrake. Critics of the show who panned it otherwise, mostly for

ideological reasons of one kind or another — you can adore Mad Men

but you can't say a good word about Promises, Promises — loved Katie

Finneran's extraordinary scene. You have to agree with the critics

about the scene, and the actress. But it's also true that Sean Hayes,

the lead, reveals a comic brilliance and timing as C. C. Baxter; and

Kristin Chenoweth has a lovely voice and compelling stage presence.

(To me the actress seems a little petite for the role, given the

slightly tough persona she is supposed to have.)

Two other things to mention:

The character of Dr. Dreyfuss is played by Dick Latessa (above, with Chenoweth and Hayes), who puts this

role on the map. Dr. Dreyfuss is the physician/wise man/priest of the

play and even invokes God, sincerely, in a moment of crisis. Also, the

number, “Where Can You Take a Girl?”, which is reprised twice by an

enthusiastic quartet of young executives, is comic and even slapstick.

We would wish to believe that the kind of thinking expressed in the

song doesn't take place any more. But it does, whatever one's moral

judgments are. It's just that today the targets are not “secretaries” but “part-time staffers”, or “interns”, or “campaign workers”, of both

sexes. “Where Can You Take a Girl?” is a spoof. Everyone in the

audience laughed, even if they didn't quite want to.

Visually, the play is saturated in early '60s office decor. (Think

kidney-shaped ash trays.) The art direction reminded me of Frank

Tashlin's 1957 Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?. But the props don't overwhelm the story and the music. The

choreography is terrific. The dancers and their costumes look right to

the period, and they're not small bodies. Yet there are also not too

many of them. The high points of the dancing occur at the very

beginning of the play and during “Turkey Lurkey Time”. (As far as I am

concerned, you could almost rename the show “Turkey Lurkey Time”, that

song is so eccentric and memorable.)

Mary and I had a blast. It's rare you do something on an impulse —

like getting on a plane within a few hours of deciding to go, with the

sole purpose of seeing one show you hope you're going to like — and it

works. Promises, Promises works. It works on almost every level. If

you are going to take offense — at anything — on purely ideological

grounds, I guess you could infer something you didn't like. That may

be true of almost any piece of popular art. But I think it would be

doing an injustice, here, to the combined talents of Billy Wilder and

I.A.L. Diamond, of Burt Bacharach and Hal David, of Sean Hayes and

Kristin Chenoweth, Dick Latessa and Katie Finneran; and of Neil Simon.

Together they bring together a story of a little yearning man and a

little beat-down woman (Kerouac's understanding of a “beat-ness”),

whose love affair becomes a big story.

RED RIVER SHORE

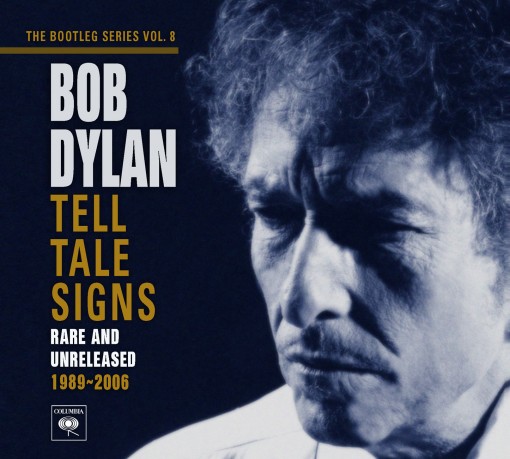

Bob Dylan’s song “Red River Shore”, from the compilation album Tell Tale Signs, has no direct precedents that I know of, but it references a couple of older cowboy songs. The first is “Red River Valley”, a standard from the second half of the 19th Century:

From this valley they say you are going.

We will miss your bright eyes and sweet smile,

For they say you are taking the sunshine

That has brightened our pathway a while.

So come sit by my side if you love me.

Do not hasten to bid me adieu.

Just remember the Red River Valley,

And the one that has loved you so true.

The last line is often rendered as “And the cowboy that loved you so true”.

This song in turn was probably influenced by (or possibly influenced) another cowboy song, based on an old English ballad, “The Girl From the Red River Shore”, whose title is a recurring phrase in Dylan’s song.

Both are songs about loss — the second describes a cowboy who gets into a fight while riding to marry a girl from the Red River shore. Her father, who disapproves of the marriage, has ridden out to meet him with a cohort of gunmen — the cowboy kills several of them and now can never go back to claim his love.

I don’t know how old this second song is — an arrangement of it was copyrighted and recorded by the Kingston Trio in the Sixties but its words have a 19th-Century feel. I also don’t know why the Red River became associated with lost love . . . it was probably just an accident, although “Red River” does suggest the coursing of the blood, the beating of the heart.

Dylan’s song was recorded during the sessions for Time Out Of Mind but left off that album for some reason. Curiously, it influenced a song on a later album, Modern Times, “Nettie Moore”. The title and the first two lines of the chorus of that song were taken from an 1857 song called “Gentle Nettie Moore”, which is about a man’s longing for a young girl who has gone off somewhere else. The older song references good times past, including boating on a river, and Dylan adds a river to the chorus of his song, after the quoted lines:

Oh, I miss you Nettie Moore

And my happiness is o’er

Winter’s gone, the river’s on the rise

I loved you then and ever shall

But there’s no one left here to tell

The world has gone black before my eyes

This echoes the plight of the narrator of Dylan’s “Red River Shore”, who goes back to the place where he knew his lost love and can’t find anyone who remembers her, or them together. In a final, mystical image, the narrator wonders if anybody anywhere ever saw him, except that girl — suggesting that he only had authentic being in her eyes, that if she isn’t looking at him he’s dead. This is why that last verse references Rabbi Jeshua of Nazareth, someone who knew how to bring the dead back to life. If the girl from the Red River shore is really gone, then the rabbi might be the only hope of life left, a dubious hope in the narrator’s estimation.

The song thus becomes something much more than an exercise in nostalgia, in romantic longing — it becomes a kind of cry of existential terror.

One day, as you drift into your fifties, you wake up and realize that you are closer to the end of things than to the beginning. It’s not necessarily a bad or depressing realization, but it does induce different kinds of thoughts than you’ve ever had before. It makes you think seriously about what your life might add up to, when all is said and done. Lost loves come back to haunt you. For me these ghosts are often sweet revenants, because they remind me of the times I did feel most alive, of the times when my being seemed fullest.

In “Red River Shore”, Dylan has written a great song about this phenomenon. It will certainly speak most clearly to people who are nearer to the end of things than to the beginning — but the truth is that this could be any of us, for all we know, whatever age we’re at, and all of us will get there eventually.

There’s a girl (or guy) from the Red River shore in every life, and eventually he or she will become a ghost, even if it’s only the ghost of the youth of someone you’ve always been with. Eventually that ghost will show up at your door one day and say, “Remember me?” . . . and the question will really be, “Do you remember who you were when you were most alive?” It’s an important question — since that memory might be the only thing you’ll take with you from this world, the only thing worth taking with you from this world.