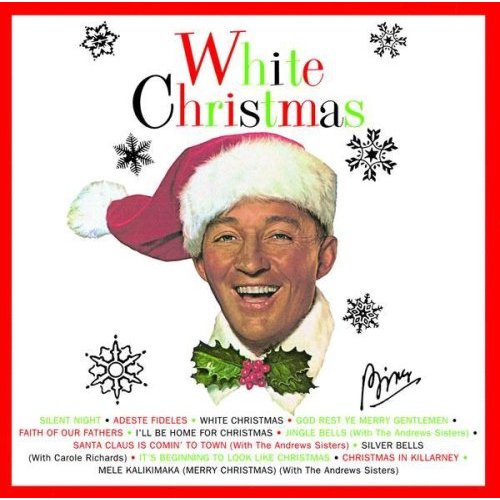

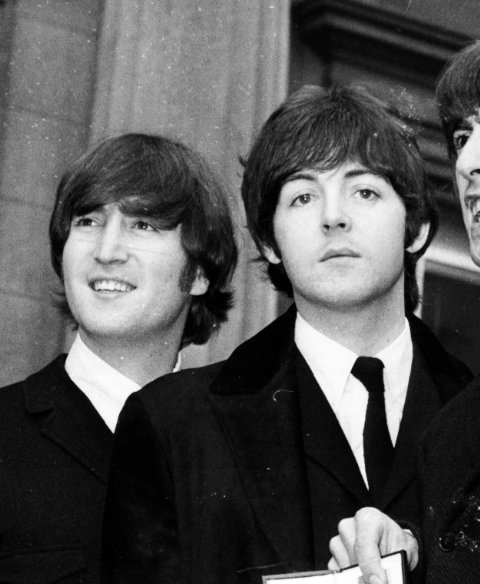

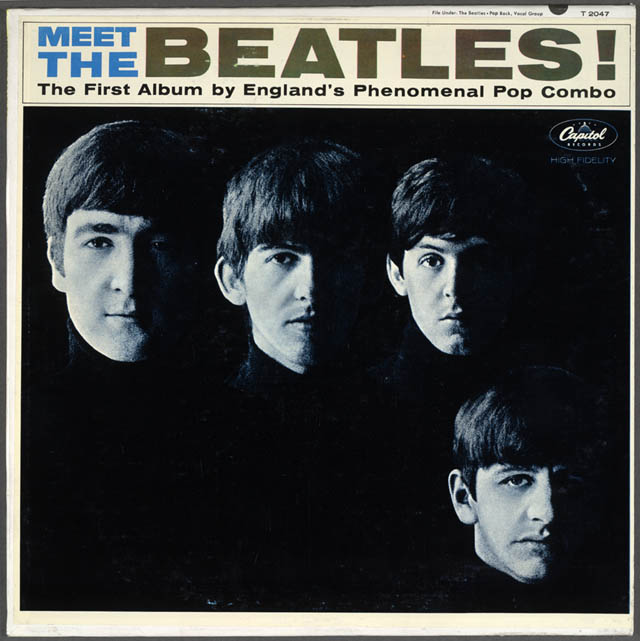

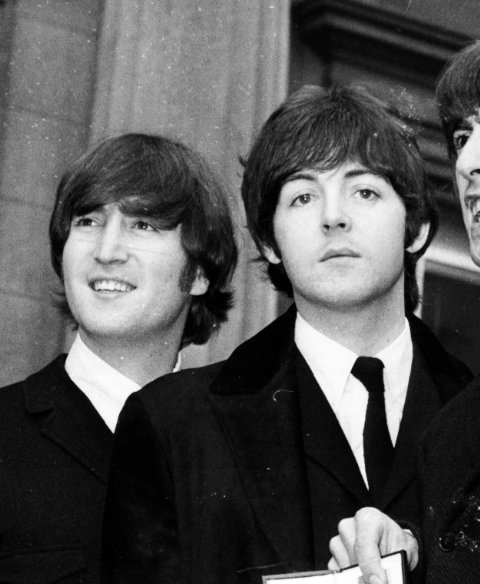

The achievement of The Beatles was centered around the songwriting craft of Lennon and McCartney. They had, first of all, a gift for melody — something that's beyond analysis, beyond fashion and beyond criticism. Irving Berlin and Abba had the same gift, and if you can't appreciate the melodies of Abba, because the group was so un-hip, or the melodies of Irving Berlin, because he wrote show tunes, you don't really like music — you've got other things on your mind when you're listening to it.

But allowing for that gift, Lennon and McCartney were craftsmen — like Abba and Berlin. They understood their pop idiom and wrote for pop's audience, for the market. When they had trouble getting a song to the top of the charts in the U. S., even as they grew more popular there, they analyzed the reasons for this and added hand-claps to “I Want To Hold Your Hand”, thinking this would give the song a more “American” feel. (Brian Epstein had earlier encouraged them to write this particular song expressly for the American market.) It worked — the song was their first U. S. chart-topper.

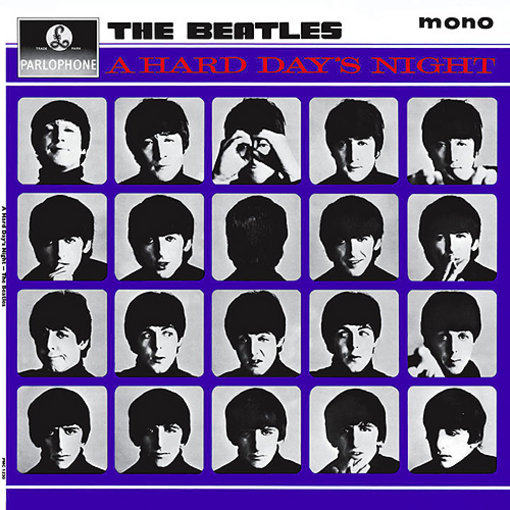

In their first few years of success the demand for new material from the team was intense and they met it with an astonishing productivity. They wrote 13 new songs for A Hard Day's Night in a matter of months, mostly on the road with a grueling concert schedule, and almost all of those songs are now revered as pop classics. McCartney said they never, when collaborating, spent more than three hours on any one song. They were consummate professionals.

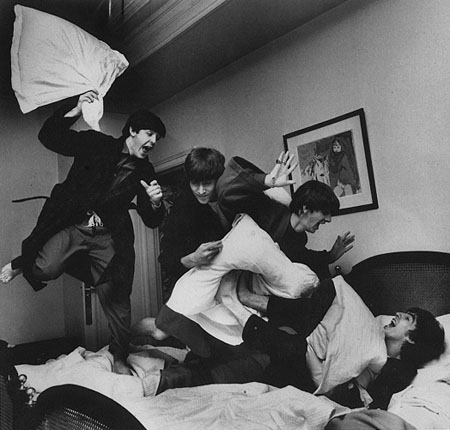

What made the group, as a group, phenomenal, was what they did with their original songs. It was a magical combination of small things. The Beatles weren't the hardest-rocking group in the world, and only Lennon had a gut-level feel for the blues roots that nourished American rock. When McCartney did his vocal impersonations of Elvis or Little Richard, he managed to leave out the sinuous rhythmic improvisation around the beat that gave those performers soul.

What they did have was, to paraphrase George Martin, ears. They were open to all the musical influences that fed pop — country-western, show tunes, British music hall ditties, and such elements of rhythm and blues as they could master. Eventually they added a new influence, Eastern music, by way of George Harrison. But they mixed them all up into their own brew, based solely on what sounded good to them. None of them was musically literate — they'd had no formal training and couldn't read music. They relied on instinct. No musical device was too corny for them, if it sounded right, yet at the same time they came up with highly unconventional harmonies that hadn't been heard in Western music since Monteverdi.

They worked within tradition but only because they'd absorbed so much of it into their own style intuitively. In an effort to reproduce American rock music they made up new twists on it, by a process of what Harold Bloom called “creative misreading”. To them, if it sounded like rock music, it was rock music, and so they expanded the idea of what rock music could be.

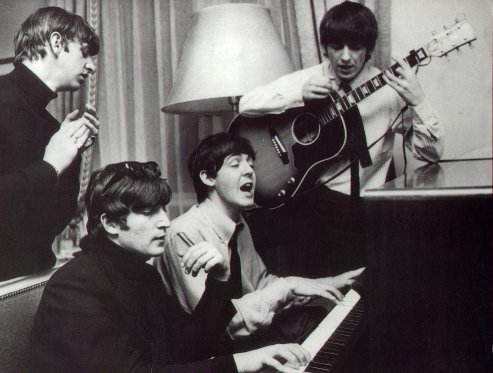

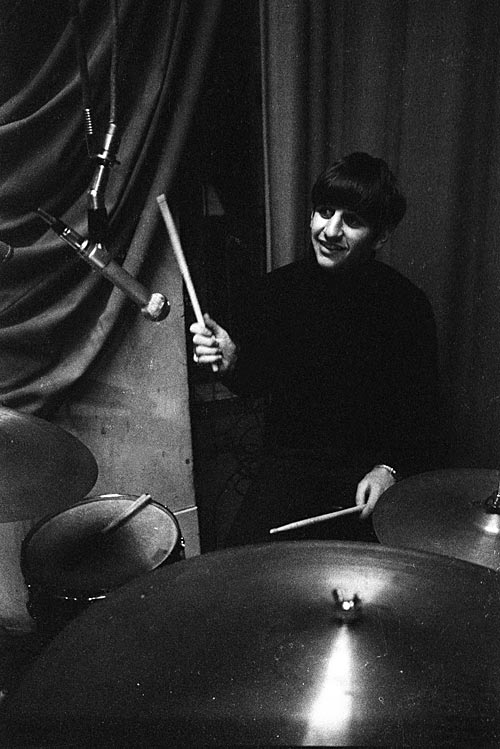

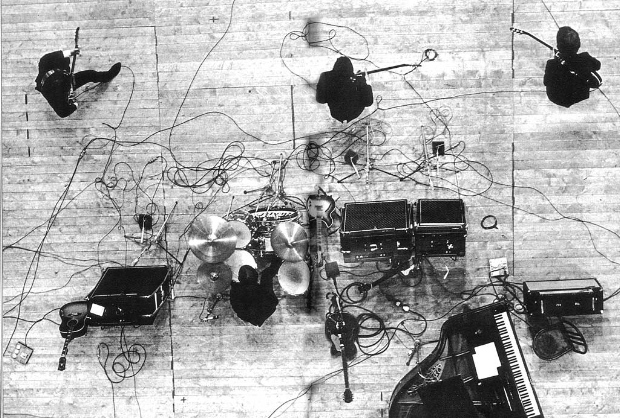

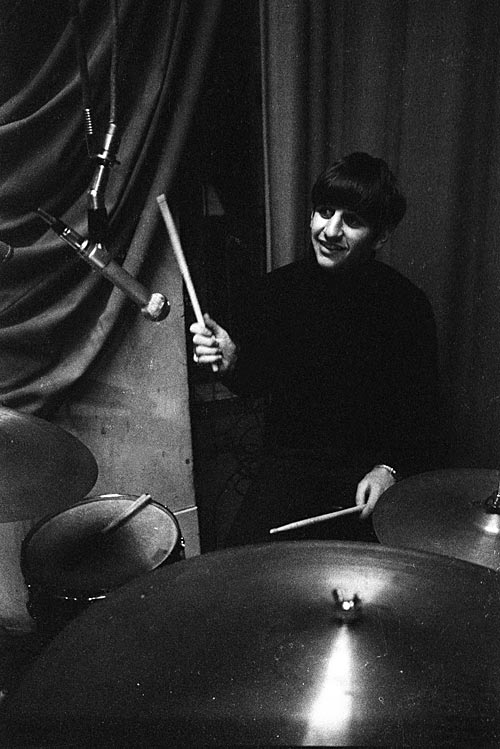

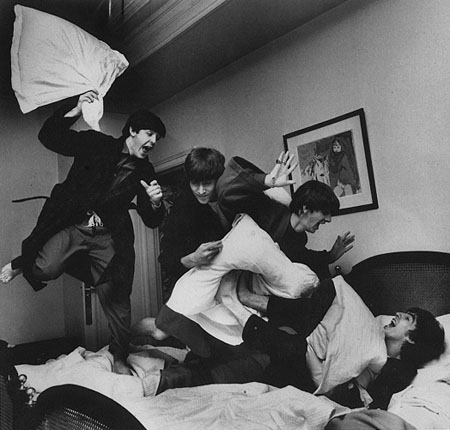

In playing their songs they also combined a lot of small, simple things into an arresting whole. Ringo, perhaps the most under-appreciated musician of the group, had a rock-steady beat and a simple style, boring and unimaginative to some, but he inflected it with a lilt, a subtle impulse that propelled every song forward joyfully. McCartney provided unusually melodic base lines which also added a subliminal lilt to their numbers — not something you had to notice consciously to feel.

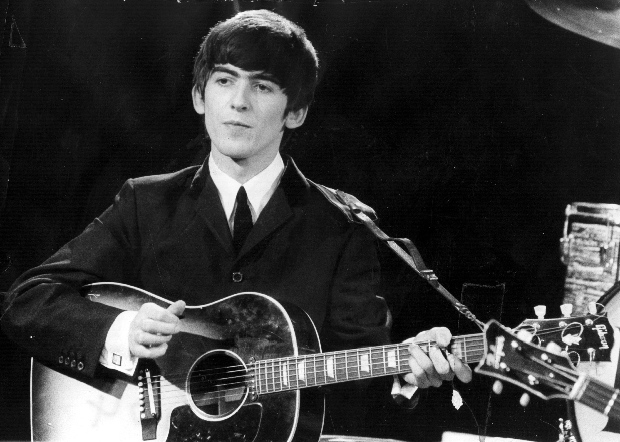

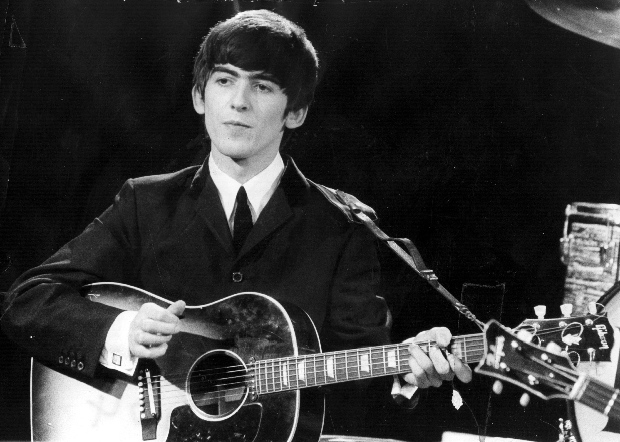

Harrison grew by leaps and bounds as a lead guitarist over the life of the band, but even his earliest riffs, when he sounds like a talented kid trying out stuff in the garage, have a sure sense of the grace notes the songs need to take them to another level. Lennon's brash, urgent work on rhythm guitar gave the group's sound at least a hint of funk.

Their vocal styles were individually distinctive but they were always ready to sublimate individuality to the sound of the whole. This gave them enormous range by very elemental means. Paul could do his crooner or his rock-shouter bits when required, Lennon could rave or insinuate sweetly — singing in close harmony together they could be something else again, a duo like none anybody had ever heard.

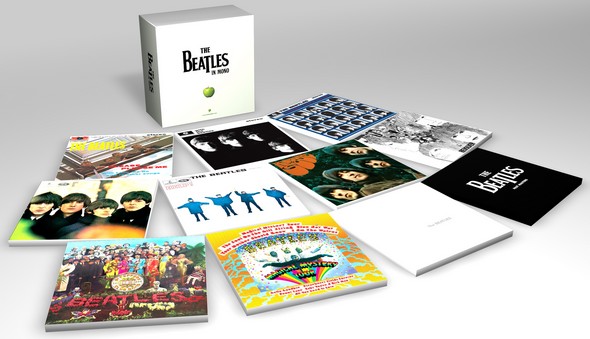

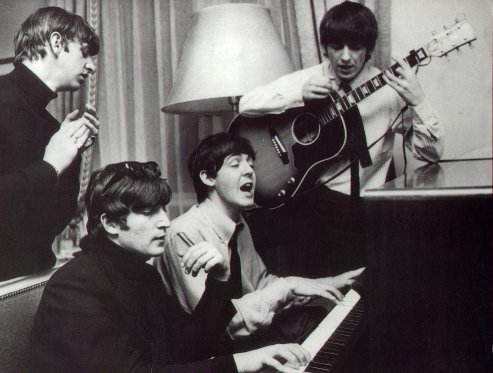

The combinations Lennon and McCartney could concoct from their individual and collaborative vocal styles were remarkable. On “A Hard Day's Night” they take turns on lead, in different sections of the song. Sometimes one will back the other with a harmony part, sometimes one will double-track his own vocal. They play around with different levels of reverb. The subtle variety of it, hard to keep up with unless you listen very closely, is one of the things that give the recording such a feeling of life and surprise, however many times you listen to it. (It's easier than ever to keep up with it, by the way, on the new remasters.)

Ringo and George had less range and virtuosity as singers but distinct qualities of their own, which added spice and another kind of variety to the mix.

Pop music isn't the most profound art form in the world, though it's capable of conveying profound truths. (“We learned more from a three-minute record than we ever leaned at school” is how Bruce Springsteen once put it.) None of The Beatles had the melodic chops of a Jerome Kern, or the literary chops of a Lorenz Hart, or the musical chops of a Louis Armstrong, or the vocal chops of a Frank Sinatra — all those residents of the pop-music Parnassus. But they used everything they did have to its fullest, they used the pop idiom to its fullest, and in the process they created miracles, one after the other, for almost a decade.

There was no artistic achievement in the 20th Century more impressive than their collected body of work. It still vibrates with the immediacy of the creative energy and the clear-eyed craftsmanship that produced it. The albums all sound as if they were recorded yesterday, as though they're being recorded live while you listen to them. This is a quality that belongs only to the very greatest art.