Yeah . . .

Yeah . . .

Yeah . . .

Yeah . . .

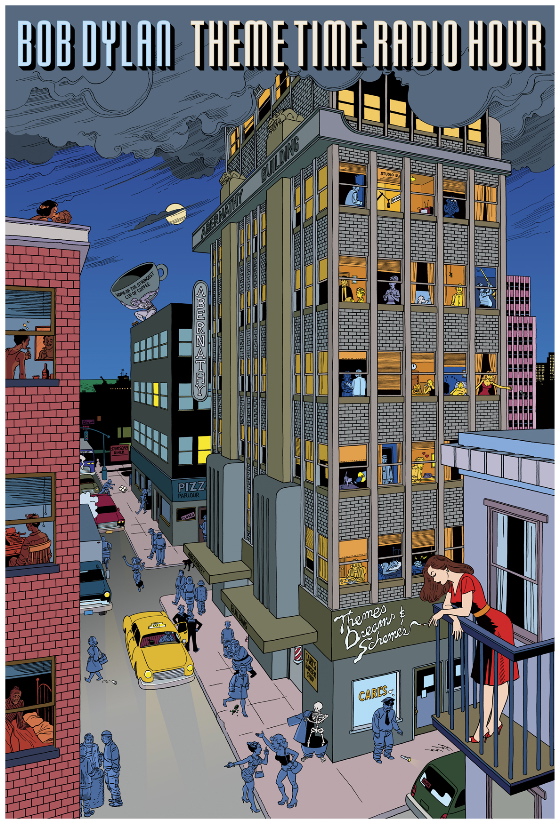

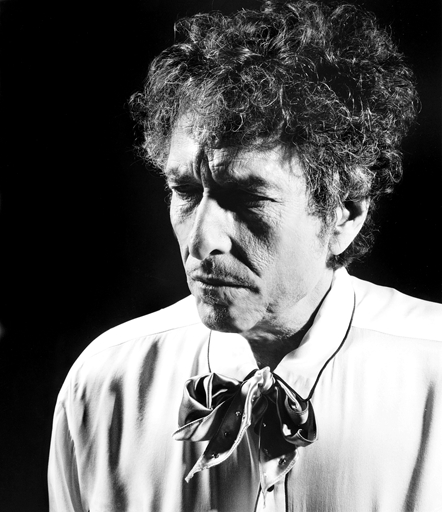

This is a poster designed by Jaime Hernandez, of the awesome comics duo

Los Bros Hernandez, for Bob Dylan's great show on XM Satellite Radio,

which might be the best radio music show of all time. Each week

Dylan plays songs he likes on a given topic. The songs are great,

but it's also great to see how Dylan organizes music in his mind.

It's much the way he organizes images in his songs — according to

associations and affinities that don't follow conventional rules or

categories.

I don't listen to the show much because like more and more people these days I have a hard

time dealing with scheduled entertainment — unless it's something live

like a baseball game. If it's digital and I can't download it or

get a copy of it to enjoy at my leisure, it's too much trouble, too

annoying — too much about the convenience of the provider and not

enough about my convenience.

[With thanks to Boing Boing for the link.]

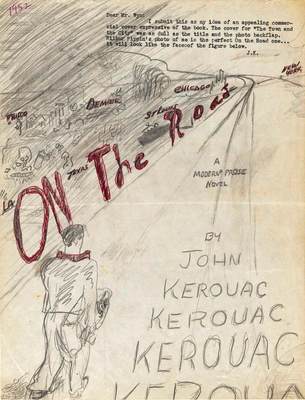

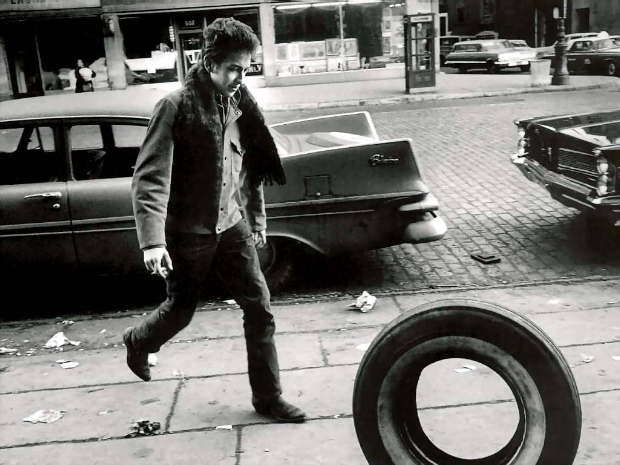

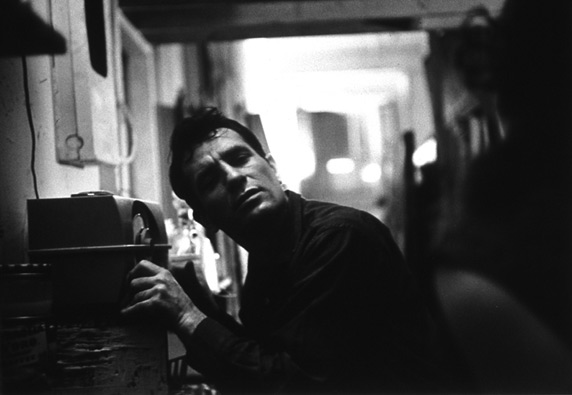

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of Jack Kerouac's On the Road

and the book is getting a lot of attention. (That's Kerouac's

design for the book's cover above.) It was certainly an important

book — crystalizing the odd malaise that gripped America after WWII

and presenting an image of the way American youth would react to it, in

increasing numbers, by cutting loose from everything, drifting into a

world of sensuality and drugs, hitting the road in search of . . .

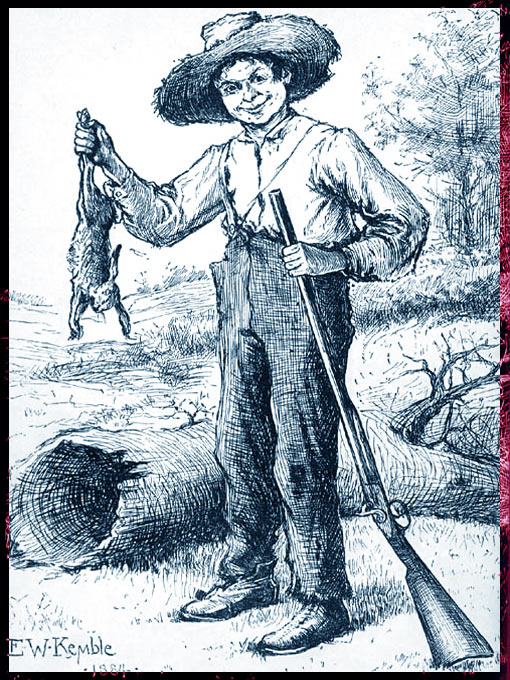

something. The book's freewheeling, lyrical prose was brilliant

enough to allow one to take it seriously as a work of art, to place it

in the picaresque tradition of Huckleberry Finn.

The moral and spiritual emptiness of On the Road's

protagonists was part of the

book's truth, of course, but that truth, to me, was a thin one, without

any deep humane dimensions — and this is nowhere better revealed than

in

the book's depiction of women. It's not just that Kerouac's

protagonist's treat them badly, or indifferently, but that they don't

seem to see them as human beings — and, more importantly, that the

author himself doesn't seem to see them as human beings. This is

quite a different thing from writing women characters badly,

unconvincingly — quite a different thing from ignoring women or even

raging against them for their otherness, as Henry Miller sometimes

did.

Kerouac simply seems to see women as an existential nullity.

Some women say this doesn't bother them — that the freedom

and exhilaration of the book's spirit is an inspiration to them as

women, however the women in the book are drawn. I can appreciate

the sense of that — but it doesn't lessen my revulsion at the way the

women in the book are drawn. It strikes me as revealing a basic

truth about almost all beat fiction and poetry — that once you get

past the attitude, the style, there's very little underneath it, and

what there is underneath it is often repellent.

William Burrough's magical, fractured prose, best appreciated in his

recorded readings of it, is invigorating and exciting — but a little

of it goes a long way. It's like a jazz improvisation on a melody

that the musician has forgotten, or never knew in the first

place. It's a gesture, an exercise, not an artistic creation.

Bob Dylan was the great inheritor of the beat tradition, but he

grounded his improvisations firmly in the blues and folk traditions —

he was engaged, with a great deal of humility, in a conversation with something beyond himself.

His early work is marred by some of the same misogyny one finds in the

beats, by images of women that alternate between goddess and destroyer,

with no convincing human presence in either.

But Dylan, unlike the beats, grew as an artist. He listened to

the culture around him, its roots and moods, and talked back to

it. His work wasn't just an interior howl, a negation — he was a

rolling stone who could step outside of himself and watch himself roll.

When Kerouac tried that he was appalled by what he saw — or didn't

see. He ended his life drunk, stoned, in a state of utter decay and

despair. We can see the roots of that in On the Road. Kierkegaard said that the precise quality of despair is that it is unaware of itself. On the Road

is a harrowing portrait of a despair that is unaware of itself — one

its author shared, unawares, with the book's protagonists.

Kerouac's defenders say that only the work matters — not the

life. But I say that with Kerouac the life is in the work — is

not

transcended in the work. Which is not to say that the book isn't an

extraordinary thing, with passages of true greatness, depictions of

places and moods that are indelible, an authentic and often moving

voice with it's its own kind of feckless grandeur. It's just to say that there's something missing from it —

some element of heart and soul and sympathy that is crucial to any great work of art.

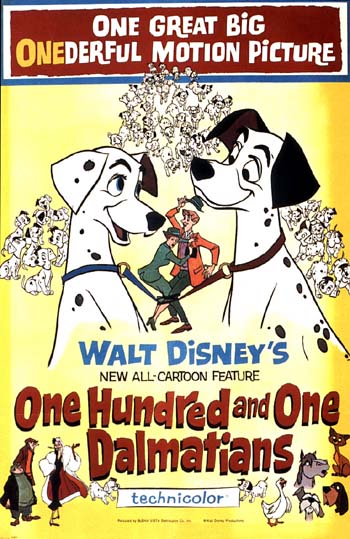

In the list

I recently linked to, showing the 100 top-grossing films of all time (domestically),

with revenues adjusted for constant dollars, there are, as you would

suspect, a number of Disney classics. Many of these films

performed only adequately on their initial release but kept making money over the years. Snow White was the only one to make the top ten but I was surprised to see 101 Dalmatians

at number eleven. This is one of my favorite Disney films but I

always thought of it as a minor work, and certainly not a

mega-hit. Apparently a lot of other people have loved it as much

as I do.

Word is that a two-disc Platinum Edition of the film, loaded with

extras, will be coming out next year, which is exciting news.

Disney also released a CD of the soundtrack a few years ago — it's a

wonderful, light, slightly jazzy score that really evokes the early,

pre-Beatles Sixties. It's now out of print but copies can still

be found on Amazon — and it's well worth tracking down.

Check out the film, too, if you don't know it — but just rent it, in

case you fall in love with it and want to grab the definitive edition

when it comes out in 2008.

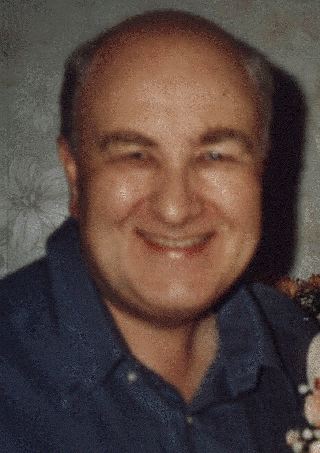

This

is Alan Fraser, an old friend from the newsgroup rec.music.dylan, which

I was once heavily involved in but have long abandoned (it got too

creepy.)

It was Alan who answered the first question I ever posted

there, around 1998, seeking track information for an import Dylan

collection called Masterpieces. Alan is the world's foremost

authority on Dylan rarities — officially released but rare or obscure

recordings. Here's a link to his invaluable web site database:

Alan

is also a fan of sci-fi and has passed along a lot of great book

recommendations in that genre. I never knew what Alan looked like until he sent this picture — he

lives in England — but I imagined his jovial smile almost exactly . .

. it's just there in what he writes, in his cheerful helpfulness. He was

the guy on the newsgroup who always answered the question of a first-time

poster with good-natured seriousness, even if it was a question that had

been asked a million times before.

Mark your calendars — the new White Stripes album Icky Thump arrives on 19 June. Meanwhile, here's a video

of the title song to whet your appetite. It seems to have been

partly filmed in a Mexican whorehouse, and the lyrics have a message

for people obsessed with illegal aliens from south of the border —

“kick yourself out . . . you're an immigrant, too.”

¡Viva Stripes!

The 20th-Century notion of “absolute music” tended to

capture the imaginations of composers who wanted to be

thought “modern”. They generally abandoned the emotional, descriptive

and/or

narrative ambitions of 19th-Century program music in favor of a more

severe system of abstraction. This marked the end of concert music as

a popular art form but not the end of program music, which went on its

merry way in movies, where it continued to enthrall a large public.

Of course, people didn't pay as much conscious

attention to this music as they used to in the concert hall, but they

could have, with profit. To prove this assertion all you have to do is

listen to the many classic film scores now available on CD — the

original tracks recorded for the films or later re-recordings of the

scores. Many of them are magnificent pieces of music in their own

right. It helps to have the “program” in mind, a memory of the films

this music supported, but it's not absolutely necessary with the very

best scores — like those of Bernard Herrmann, for example.

Hermann didn't specialize in creating memorable

melodies but he was a master

at using the colors of an orchestra to evoke mood and he had a great

and subtle understanding of the dramatic uses of rhythm. All of his

Hitchcock scores are brilliant, even the less famous of them like the

score he did for The Wrong Man. Edgy, dark, minimalist, jazz-inflected, it

perfectly mirrors the bleak and jagged realism of Hitchcock's 50s-era

New York

City, its dehumanizing institutions and its spiritual

chaos. But it has a lyrical core,

too, that echoes the protagonist's yearning for deliverance.

It's not absolute music, to be sure — but it's

absolutely wonderful.

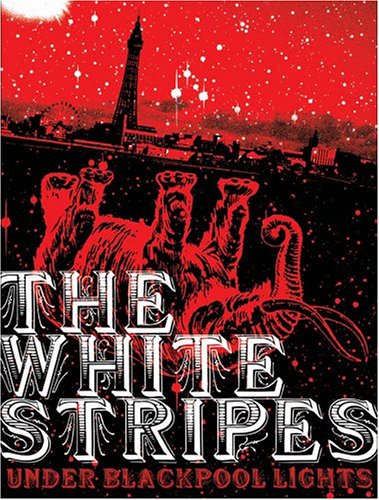

If

you haven't seen the White Stripes concert DVD Under Blackpool

Lights, check it out immediately. Shot entirely on 8mm it's a gorgeous thing —

sort of a cross between The Last Waltz and the Zapruder footage. You

can buy it here:

Under Blackpool Lights

From my sister Lee:

In

1985, I went to see Doc Watson perform at Thalian Hall in Wilmington,

North Carolina. When summoned for his encore, he announced, “Now

I’m going to sing America’s second national anthem.” And he began

to play Dixie. The

audience went insanely wild, feet stomping, hysterical cheers. It

was thrilling. I was totally swept away.

And for years after, it continued to bother me. Why was it so

thrilling? What did it mean? I just couldn't figure it

out. The Civil War seemed to be so simple for Northerners, and

still so complicated for the rest of us. So I forgot about Doc

Watson and Dixie,

felt embarrassed by it, and rather guilty too, and chalked it up to

another mysterious, uncharted connection to my “country.” Then, last

summer, after leaving the Civil War battlefield of Chancellorsville with Lloyd, my mom and my two

kids, with my head full of ghosts, and a vision of Robert E. Lee

swinging his hat over his head, his eyes gleaming with victory, I asked

Lloyd if his miraculous i-pod contained within it the song Dixie, and if so, to play it. It did, and he did.

Since then, I have located Bob Dylan’s version of Dixie.

And I play it a lot. But I’m careful to close all of my windows,

so that no one can hear it. My neighbors are

African-American. I like them, and I’m worried they will think it

is racist to listen to this song. I pause it when the mail man is

close to the house. It’s like a dirty secret. And this

gnaws at me.

So I did some research into the history of the song Dixie,

and, like the song itself, I found it both comforting and

disturbing. The authorship is generally attributed to Daniel

Decatur Emmett, of Turkey in the Straw

fame, an Ohioan who allegedly wrote the song in 1859 while living in New

York City. A competing account tells us that the song was really

an old African-American tune revived by the black musician brothers Ben

and Lou Snowden, whose joint tombstone proudly declares “They taught Dixie to Dan Emmett.” Either way, the song was a smash hit, particularly in the North.

When Abraham Lincoln first heard the song in Chicago, he shouted “Let’s

have it again! Let’s have it again!” By all accounts, it

remained one of his favorite songs, before, during, and after the Civil

War. “I just feel like marching, always, when that tune is

played,” he said. When the war was over, he made a special point

of requesting it at public events. “That tune is now Federal

property and it is good to show the rebels that, with us in power, they

will be free to hear it again…I insisted yesterday that we fairly

captured it..and that it is our lawful prize.”

It is unconscionable that almost a hundred years later, psycho white supremacists used the song as a sparring partner for We Shall Overcome

during the Civil Rights Movement, associating it (really, I

believe, for the first time) with institutionalized racism. It

was a despicable and cowardly answer to Lincoln’s generosity. But

if “possible use by psychos” is a litmus test for a thing’s viability,

then we shall have to throw out a good many things, the Christian

church and our own government for starters.

In my research, I stumbled on this quote from Howard Sacks, and despite

the fact that he is an academic, I quite liked it. He says, “What

[Dixie]

tells us is that black, white, male, female, southern, northern, slave,

free, urban, rural–these aren’t separate realms. The story of

the American experience is the story of the movement between these

realms.”

Which, naturally, brings Elvis Presley to mind. Clearly, it was

no accident that Lloyd’s astoundingly brilliant Navigator preceded our

tour of Chancellorsville with a visit to Graceland. Elvis sang Dixie,

and if there was ever any American who was not a racist, it was

Elvis. His heart and his instincts on that score were pretty near

perfect.

So here’s what I’m wondering: If Abraham Lincoln claimed Dixie

as his prize of war, why can’t we reclaim it as a prize for our

heartbreak? Heartbreak that we ever tolerated slavery in our

country for even a nanosecond, heartbreak that we ever took up

arms against each other and heartbreak that all too often we let

Lincoln down. I don’t see why we can’t do that.

Dylan's version of Dixie can be found on the Masked and Anonymous soundtrack album.

Amazon’s resident critic says that Get Behind Me, Satan

is the White Stripes’s strangest and least focused

album but also their finest — and that’s not a bad summary. As with a

lot of great Bob Dylan albums it gives the impression of someone

rummaging around in the attic of American music and American culture

looking for answers to some desperate personal problems — and even if

the answers aren’t always forthcoming, there’s still the consolation of

realizing that there are a lot of cool and scary things up there.

Jack White on this album bumps into a lot of ghosts and has a disturbing

encounter with Rita Hayworth as he deconstructs his garage band style

and inflects it with deranged pop and country interpolations. He’s

always done this sort of thing musically, tying it all together with

his strong blues-based guitar — but this time nothing gets tied

together too neatly. It’s almost as though he’s thinking out loud in

the studio and letting us eavesdrop on the session.

The result is raw and silly and powerful and eloquent by turns, defying the slick sound and off-the-rack attitude that homogenizes most bands these days, even those in the neo-rock movement the Stripes have spearheaded.

Jack and Meg are simply continuing their conversation with every tradition of

American popular music — powered by the blues but ranging

far beyond them . . . on a spiritual and anguished search for the soul

of the times. In his liner notes to the album Jack rails against the

sarcasm and irony of pop posturing today — he wants us to face the

terror squarely. The White Stripes, like the great bluesmen that

inspired them, are taking on the devil himself — determined to get at

least a few steps ahead of him before it’s too late.

Here’s a link to the music video of one of the album’s best songs:

Blue Orchid

Please

join the RIAA boycott in March. Just for the month of March don't by

any music released by the major record labels represented by the RIAA.

It will be good for your soul.

The

RIAA is one of the biggest, richest and ugliest of the corporate

organizations trying to keep a stranglehold on the conversation of

culture. The RIAA has spent millions of dollars taking kids to court

for sharing copyrighted music over the Web, essentially trying to

criminalize an entire generation, and is now trying desperately to shut

down local wireless hot-spots by promoting a bill that would make any

wireless network provider legally liable for any activity that occurred

over that network, including the sharing of copyrighted work — which

would effectively end local wireless service. No local provider could

ever hope to match the RIAA's legal and financial resources — just

responding to one of their lawsuits, even a groundless one, would put the provider out of business.

I

don't advocate piracy but the RIAA is trying to create a world in which

the state enforces a monopoly distribution system owned and controlled

by large corporations. The willingness of the record labels

represented by the RIAA to destroy local wireless service in its

infancy is a sign that they've become some of the most vicious mad dogs

of corporate tyranny — blind to any values or any new technology which

might interfere with their desire to perpetuate outdated business

models and gain total control over the distribution of culture.

What

does the boycott mean? Well, at its worst, for one month you don't buy

any Bob Dylan albums, since Sony belongs to the RIAA — but you can

still go see him in concert. At its best it means that you can buy all

the White Stripes albums you want, because they don't release through

an RIAA affiliate. Go Stripes!

At

its very best it means that you can look for and buy new music by

artists who reject the madness of the corporate distributors . . . on

MySpace or at Internet music distributors like eMusic.

If you want to find out what music is covered by the RIAA just go to RIAA Radar and do a simple search.

It's only a month, it won't bring the RIAA to its knees — but it's a start. Do it and tell everyone you know about it.

For more info on the RIAA and the boycott, go here.

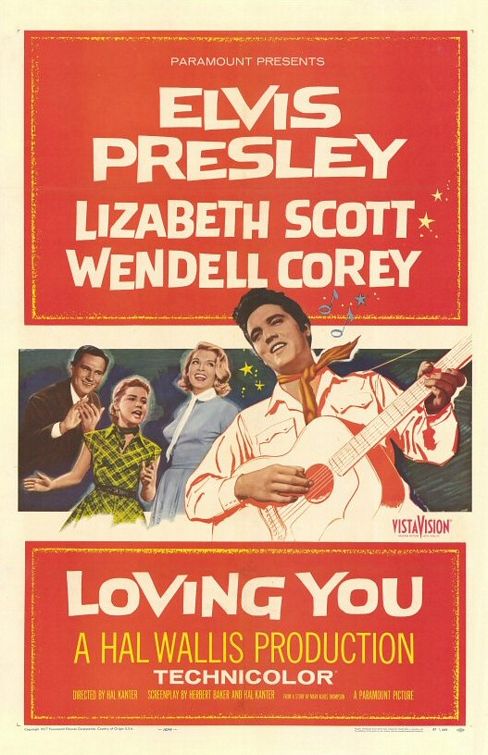

This film, has nothing — whatsoever — to recommend

it . . . except Elvis Presley in his prime and a bunch of decent early

Elvis songs. Of course, that's enough.

The story, which riffs superficially on Elvis early

career, is contrived, the dialogue thuds along without even a whiff of

wit or believability, the photography is dull and the directing is

ham-handed. But the young Elvis prowls through this wasteland of

mediocrity with an almost feral grace — as innocent as a panther, and almost as beautiful.

He

doesn't seem to realize himself the power his

combination of virility and sweetness projects, and that naivete is

part of his charm. Unless you were there, and of a certain age, it's

probably impossible even to imagine the effect his persona had when it

appeared as if from nowhere in the middle of the Eisenhower years.

America still hasn't gotten over it, and probably never will. He's

become part of what it means to be American.

When you watch this film — Elvis's third, and first in

color — just sit back, endure the exposition, and wait for the miracle

to manifest itself . . . every time Elvis shows up on screen.

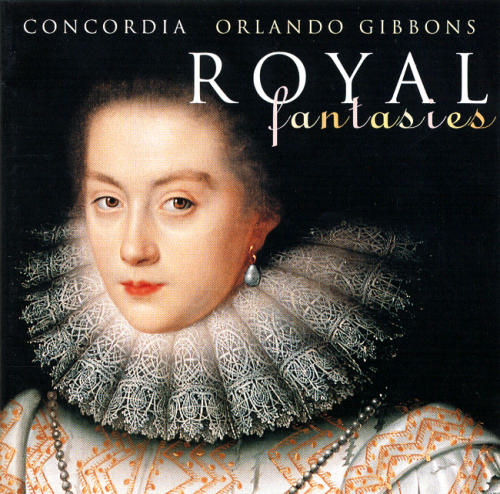

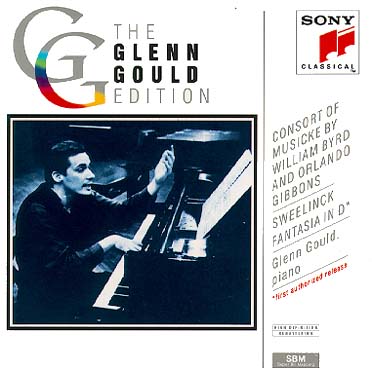

I’ve been reading a lot about Shakespeare recently and somewhere in that reading I ran across a mention of Orlando Gibbons, the other great English composer of the Tudor era (besides William Byrd.) I decided to check him out, particularly after leaning that he was Glenn Gould’s favorite composer.

Gibbons can be appreciated as a sort of alternative to Bach, with the same logical clarity but more theatricality, whimsy and lyricism. You can hear the cultural giddiness of Elizabethan England in Gibbons’s work, as you can in Shakespeare’s poetry.

Gould only recorded a few pieces by Gibbons but they’re fascinating performances. Highly expressive, Romantic even, they violate historical style but somehow evoke the essence of the music, in ways stricter interpretations, on more appropriate instruments, sometimes

fail to do.

There are worse ways to spend an evening than listening to the music of Orlando Gibbons. If you have a fire and a glass of good red wine and some strong English cheese — an old cheddar or Stilton would do perfectly — so much the better.