Part Two — The Case For the Defense

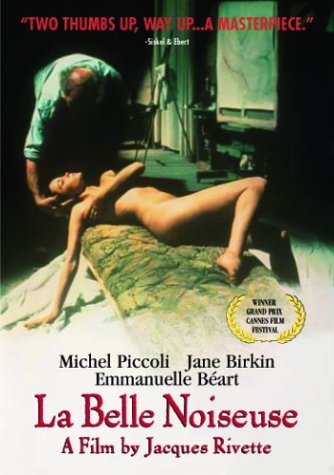

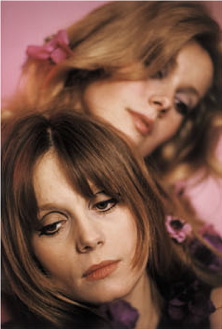

As I wrote in the first part of this look at Jacques Rivette's La Belle Noiseuse, the film can be appreciated on one level as sheer melodrama. The tensions of the story are so well established and developed that one's attention is riveted on their inherent suspense throughout the whole four-hour length of the film. The acting, especially by Michel Piccoli and Emanuelle Béart, is very fine — nuanced but intense and alive.

The characters' understanding of what is happening to them may be facile, and it may seem to mirror the filmmakers' understanding of what is happening to them, but the dramatic dynamics of the story are sound and believable and well-observed.

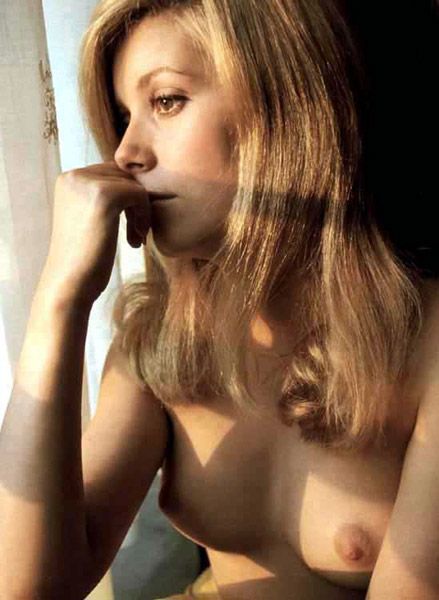

But the level on which the film truly excites is the documentary. A great deal of La Belle Noiseuse simply records the process of an artist working with a nude model. Piccoli, as I say, is convincing as the artist, but much of his work is shown in close up, with the hands of a real artist creating works on paper and canvas before our eyes. All of the film's intellectual claptrap about what art is dissolves in the miracle of art coming into being in real time while we watch.

In all of these passages, Béart is naked before us, too. There is so much nudity that we cannot read any of the passages as a “nude scene” — as that conventional and usually contemptible device which presents the exposed female body as a sop to the male gaze, a titillation, a visceral punchline. We see the whole woman here, as the artist is trying to see her, not in bits and pieces, not as tits and ass, but as “the nude” — a glorification of the female form, and the female essence.

The sight transcends the erotic and becomes powerful in another way — as a symbol of the male's eternal struggle for existential gravity, part of which has always involved paying homage to, celebrating, female power.

Nudity in modern films is almost always obscene. The idea that it can sometimes be done with “body doubles”, flashing a little tit here, a little ass there, is beyond obscene — it is depraved. It doesn't just commodify women, it exposes the full cowardice of the collapsed male psyche.

If La Belle Noiseuse did nothing more than strike a blow against this depravity, take a small step towards the redemption of the female nude in art and culture, it would be an important film.