My friend John Sosnovsky was just in town and brought as a gift a copy of Just Enough Liebling,

a collection of A. J. Liebling's writing about food, boxing and

war. In one of the articles about food Liebling offers an

extended paean to Tavel, the rosé wine from the Rhône region of France. It brought back many

memories. Tavel is a wine often served in the South Of France

with seafood (although Liebling insists it's so good it can go with

anything) and I've drunk it with many fine meals in that part of the world,

usually in restaurants or on the terraces of restaurants with a view of

the sea.

On John's last night in Vegas I tracked him down in the card room at

Caesars around 9pm. He'd been playing poker all day, with mixed

results, and said he was pokered out, so we decided to meet at Mon Ami

Gabi, a terrific French bistro in the Paris, Las Vegas casino.

Once installed on its very pleasant terrace I discovered that they had

a Tavel on their wine list, and John and I decided to drink a bottle in

honor of Mr. Liebling. And we decided to drink it with steak, to

test Mr. Liebling's assertion that it can go with anything.

It went exceptionally well with the steak, with the brisk night air and

with our conversation, which kept circling back to the upcoming fight

between Ricky Hatton and Floyd Mayweather, Jr. next Saturday in Las Vegas. John

is a member of the Fancy and very knowledgeable about boxing, but even

he seemed baffled by the question of who was likely to prevail in this

contest — Hatton, the brawler with heart, or Mayweather, the scientist

with lightning-fast but hardly lethal hands and canny instincts for

defense (or unseemly evasion, as some consider it.)

The best we could surmise was that Hatton had a chance only if he got

inside and ripped Mayweather apart with body shots, shocking him and

breaking his will. That didn't seem likely, but it seemed

possible. Such imponderables are what have made this fight one of

the most anticipated in ages. Mr. Liebling, long since deceased,

would have had much to say on the subject and we missed his wisdom

keenly.

After the Tavel and the beef, John decided that perhaps he wasn't

pokered out after all. We set off to see what tables might be

going in the Paris' card room.

The night before, at the Palms, John had cajoled me into

sitting down at my first no-limit Hold-'em game in a casino. (I'd

played a few hands at a no-limit game in the old card room at the

Rancho Fiesta, but it had broken up almost as soon as I arrived at the table.) I

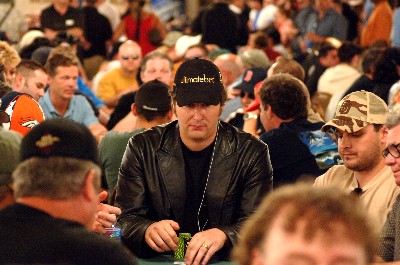

was terrified of playing at the Palms — not least because Phil Helmuth

(below, playing in a tournament) and Layne Flack, two high-profile

high-limit poker pros, were hanging

around my table to watch a couple of their friends play. It's

tough to make your debut at a no-limit table under the eyes of a winner

of the Main Event at the World Series Of Poker. (Helmuth won it in 1989 at the age

of 24, the youngest player who's ever done so.)

No limit Hold-'em is intrinsically terrifying. Any amount of

money can be bet on a hand at any time, which means you can lose every

chip in front of you if you call an “all-in” bet with the

wrong cards in the wrong situation. On the other hand, you can

use big bets to push your fellow players around — to make them fold

better cards than you have, for example. It's a wild and

exceedingly complex endeavor.

Miraculously, as soon as I sat down at the table I felt cool and

perfectly in command of things. I've played endless hands of

no-limit poker for fake money online and I understand the dynamics of

the game — far better than I've ever understood the dynamics of limit

Hold-'em, where you can bet only certain fixed amounts. I've

always played limit Hold-em because it seemed on the face of it less

risky.

No-limit Hold-'em for money, however, is a far more logical game,

far less dependent on the random fall of the cards, though the logic is

sometimes the logic of ruthlessness and terror.

I played for three or four hours in this heady atmosphere and walked

away about a hundred dollars down. Not good — but not

devastating, either. You can pay more for a good meal or a rock

concert and not enjoy either half as much or for half as long.

There were no poker pros hanging around the Paris' card room (above) — just a

lot of genial players who seemed like people on vacation

looking for a good time . . . and to say they'd played poker in Las

Vegas. They weren't bad players but they played too many hands,

eager for action. I waited for my chances, bet hard when they

came and walked away three hundred and thirty dollars ahead — by far the most money I've ever won at any poker table. More importantly, it left me over two hundred dollars ahead for my first two nights of no-limit poker.

John did even better, walking away over seven hundred dollars ahead — covering the cost of all his poker playing in Las Vegas and his hotel room and

his flight here, with a little left over for celebratory drinks

afterwards. To say that we raised our glasses joyfully would be

putting it

mildly.

[The snapshot of the Paris poker room above is from a useful web site, vegasrex,

which describes and reviews the various card rooms in Las Vegas and has a lot of other stuff about what's going on in town.]