Frank Tashlin's comic critique of American culture was

so anarchic, so all-inclusive — encompassing even the cinema itself,

the medium he worked in — that it's hard to identify a point of view,

a philosophy, behind it. He just seemed to celebrate the idea of

transgressive thought.

Still, critics have often intuited a dark side in

Tashlin's work, which suggests that it might not have been as

innocently and cheerfully irresponsible as it seems. Peter Bogdanovich

wrote, “As comic as Tashlin's movies are, they also reflect a deep

unhappiness with the condition of the world.”

But what might have been the source of this

unhappiness, the perspective on the world which determined it?

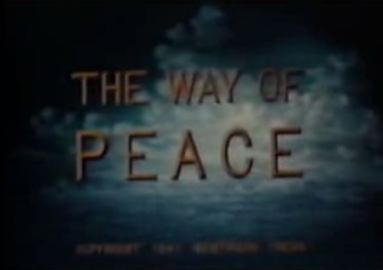

An interesting clue can be found in a short, 18-minute

stop-motion animation film he made in 1947 called The Way Of Peace.

My friend Paul Zahl, a distinguished Anglican theologian, recently

tracked down a copy of this obscure film — which is surprising, even

startling.

Tashlin started out in the world of animated cartoons,

and a few years before beginning his career as a live-action feature director

he made The Way Of Peace — which was, as far as I can

tell, his only foray into stop-motion puppet animation. The

stop-motion work was done by Wah Ming Chang, who later did the

stop-motion effects for The Seven Faces Of Dr. Lao and The Time

Machine. The film was narrated by the actor Lew Ayres.

But

here's the startling part — the film was made for

the Evangelical Lutheran Church Of America, and it's an unabashedly

religious, Christian work. Most of it is concerned with the

destruction of the world by nuclear holocaust, presented as an

inevitable consequence of abandoning Christ's “way of peace”. (A

Lutheran pastor provided the “story conception” for The Way Of Peace, but

Tashlin wrote the script and clearly devoted a lot of care to the

inventive, often beautiful, often terrifying images of the film.)

One might think, given the puppet-cartoon medium it's

made in, that it was a film addressed to children — but the

apocalyptic destruction it portrays is very dark and disturbing. At

any rate, it's probably not something you'd want to show to very small

children — the natural audience for animation of this sort.

It turns out, however, that Tashlin wrote a number of

picture books for children which are far more explicit in expressing

his fears for human civilization than his Hollywood movies ever tried

to be. Tashlin's fears were founded on a dread of nuclear war but also

on the spiritual decline of civilization through materialism —

something he satirized mercilessly in his films.

Tashlin being Tashlin, of course, his critique of the

modern world did not preclude a critique of the church — he was no

apologist for organized religion. A church is shown being obliterated

in the finale of The Way Of Peace, and one of his children's books, The World That Isn't, criticizes churches for their complacency.

I think all of Tashlin's work needs to be re-examined

in light of The Way Of Peace and his children's books. The Way Of Peace even offers a clue as to Tashlin's oddly affectionate, even

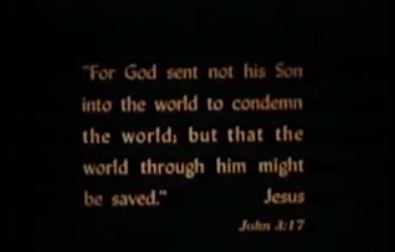

celebratory style of satire. The short ends with a quote from John's Gospel:

Paul

Zahl points out that there is Tashlinesque irony in the quote, since

we've just witnessed the destruction of the entire planet — but the

theology is sound enough from a Lutheran perspective, and perhaps from

Tashlin's. God hasn't destroyed the world for rejecting Jesus, the

world has destroyed itself by rejecting Jesus's “way of peace”. There

is no judgment involved, per se — just a kind of spiritual physics that reflects a very grim view of human nature.

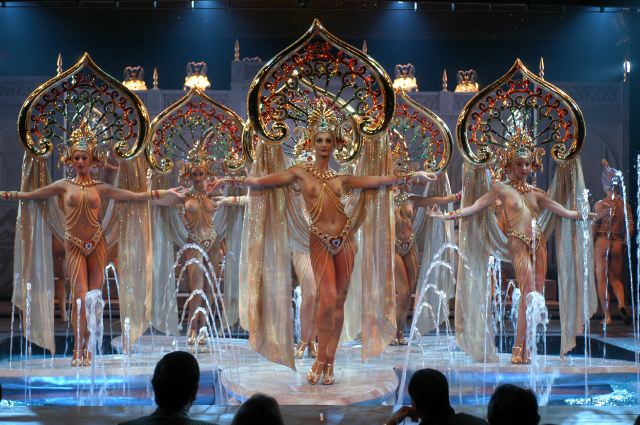

Tashlin's mainstream Hollywood work never passes judgment on anyone or anything (The Girl Can't Help

It!) . . . but was it meant to save sinners, instead of just tweak them

for

their follies?

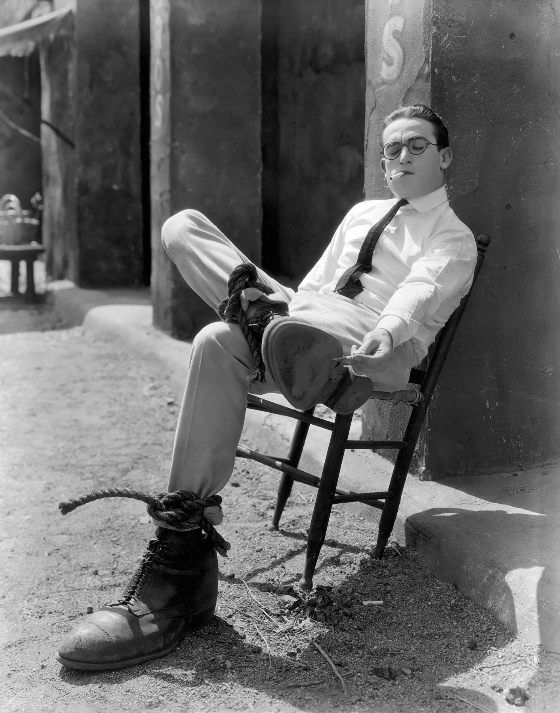

Tashlin, along with his disciple Jerry Lewis, was

probably the most eccentric director of comedy in 50s and 60s

Hollywood. Was he perhaps even more eccentric than we've imagined —

and more profoundly serious in his deconstruction of American

civilization? In The Way Of Peace he

portrays a puppet world on the brink of annihilation. Was that

perhaps what he was trying to do, between the lines, in his live-action features as well?

Another of his children's books offers an intriguing image which might be the best clue to the real Tashlin and his methods — The Possum That Didn't.

In it, a happy possum hanging upside down has his smile mistaken for a

frown. A bunch of do-gooders take him to the city, where he's

unhappy, but his upside-down frown there is mistaken for a smile.

To

me this sounds an awful lot like a warning directed at anyone inclined

to take Tashlin's topsy-turvy comic vision at face value. At the

very least it should make us question whether his smile is ever quite

what it seems.

[The Way Of Peace can now be seen, in a somewhat

fuzzy online version, at the web site of the Evangelical Lutheran

Church Of America, which holds a copy of the film. It's really a

remarkable and provocative piece of work. Thanks are owed to that

organization for putting it up, and to Paul Zahl for tracking it down

there.]