Pandora’s Box, the film Louise Brooks is best known for, is one of the sublime works of cinema, not least because of her performance init.

It is not exactly a film adaptation of the famous play by Franz Wedekind on which it is nominally based — it is better appreciated as what it calls itself, a “variation on themes” from Wedekind’s work. Wedekind created in his central figure of Lulu an almost mythological incarnation of the terror the feminine inspired in late Victorian men, who simply didn’t know how to relate to women outside the collapsing domestic structures of modern industrialized societies. Wedekind’s Lulu was a calculating vamp, an anarchic force, unrestrained by the old female roles, and thus could be experienced as an alien and malevolent power.

Pabst’s and Brooks’s Lulu is something else again. Her destructive power is not defined by her deviance from old female roles but by the utter collapse of manhood around her, by the failure of men to adapt to the new empowerment of women. The crucial event intervening between Wedekind’s play and Pabst’s film was the cataclysm of WWI, which confirmed not just the collapse but the inherent weakness, the dry rot at the heart of the 19th-Century European patriarchy. From a post-WWI vantage, Pabst, by instinct or calculation, realized that blaming women was not really an answer or a solution to the failure of modern manhood.

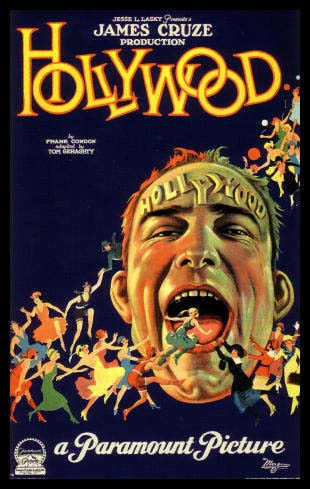

Pandora’s Box shares aspects of an attitude that wouldn’t find its way into American film until after the cataclysm of WWII, specifically in film noir, where a sense of the futility of male power slammed head-on into the contingent terror of the female, the femme fatale.

But Pabst’s film is more mature, ahead of its time even, in making Lulu’s female power innocent, neutral, a mere fact of life, which men simply have no resources to engage on equal terms.

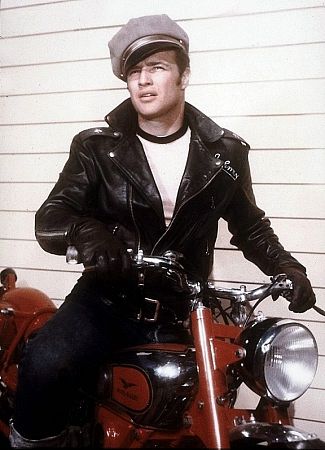

In Pabst’s film men destroy each other and destroy themselves trying to engage Lulu’s existential sexuality. They try to commodify her, reduce her to images, trade her for money. They fail at every turn to diminish her. And yet they must keep on trying, since they can’t have meaningful intercourse with her as she is, and this is a constant reminder of their own impotence. Early in the film Lulu tells her current benefactor, “The only way to get rid of me is to kill me.” Her sexuality cannot be dismissed any more than it can be engaged — it can only be destroyed.

This explains the curious ending of the film, in which Lulu meets a contemporary version of Jack the Ripper in London and is instantly drawn to him. He is in a sense the only

honest man in the whole tale — he worships Lulu, like all the rest of the men in her life, knows he’s no match for her, knows the only way he can deal with her is by killing her. Which he does — but not before paying touching tribute to her majesty, crowning her with Christmas mistletoe, in images that glow with tenderness and sacramental mystery.

Lulu almost seems to acquiesce in her own sacrifice — a final extension of the detachment she displays throughout the film. It’s not her job to tell men how to be men — she can only observe the failures of their doomed attempts to figure it out for themselves. She observes with interest, certainly, sometimes with awe, but never with a sense of personal responsibility. Compromising her female essence to accommodate the impotency of men is not a solution for her, or for her lovers.

Brooks’s incarnation of this role is brilliant in the extreme, one of the finest pieces of acting in all of movies. Her work is neither minimalist nor merely naturalistic — just “being herself” . . . whatever that might mean in the utterly artificial, high-pressure context of a film set. Pabst was clearly drawing on aspects of Brooks’s own personality in the film, but the result is a “created” character of great complexity, one which never resolves itself into any conventional type or relies on any conventional response. Brooks’s performance has inwardness and mystery, as Shakespeare’s characters do, as Chaplin’s and Keaton’s characters do.

Pabst’s and Brooks’s Lulu is almost unique in modern art — neither a demonized icon of male fear nor an idealized icon of female ambition. She doesn’t want what men have — she wants men to recover what they once had. She wants partners. Finding none, abandoning hope, she resigns herself to oblivion, but not before accepting, graciously, Jack’s grotesque and pathetic tribute to what has been lost.