A cartoon-moderny greeting from the Disney studio — the classic characters don't look quite right in the style, but we overlook that in the spirit of the season.

UNNERVING

Matt Barry over at The Art and Culture Of Movies has recently posted an insightful short review of Orson Welles's Touch Of Evil. He calls it an unnerving film, which it certainly is, but points out that one of its most unnerving aspects is the way Welles goofs on our expectations of what a gritty little film noir should be.

The film's extreme stylization both seduces us into its nightmare world and distances us from it as an aesthetic creation, all at the same time. Touch Of Evil was not quite the last classic noir — I think you'd have to give that distinction to Odds Against Tomorrow, which came out a bit later — but its self-consciousness about the form was a sure signal that the tradition had all but played itself out. One definition of a neo-noir is that it's at least as concerned with commenting on the form as with working inside it. In some ways, Touch Of Evil was the first of the neo-noirs.

HAVE A DOTY CHRISTMAS!

Some holiday cheer from Roy Doty . . .

SNOW!

[Image © 2008 John Gurzinski/Las Vegas Review Journal]

It snowed in Las Vegas yesterday — almost four inches of the stuff fell around the valley, much more in some places. It was the biggest snowfall since 1937, when records of such things started to be kept. McCarran Airport was shut down. Girls wearing Ugg boots, which usually seem so preposterous out here in the desert, were the only people prepared for the event.

Having worked all night and crashed in the morning, I slept through most of it, so it was surreal beyond words to wake up briefly in the late afternoon, wander into the kitchen for some water and peek out the window — the Strip was barely visible through the veil of white. I turned on the radio to confirm what my eyes had apparently seen — a snowstorm in Sin City. It felt very cozy to get back in bed and doze off again.

Before dawn now, as I write this, the snow has stopped but there are still patches of it on the ground, on the pine trees and the steps outside my apartment. A strange visitation.

HOLIDAY GREETINGS FROM HAROLD GRAY

Arf!

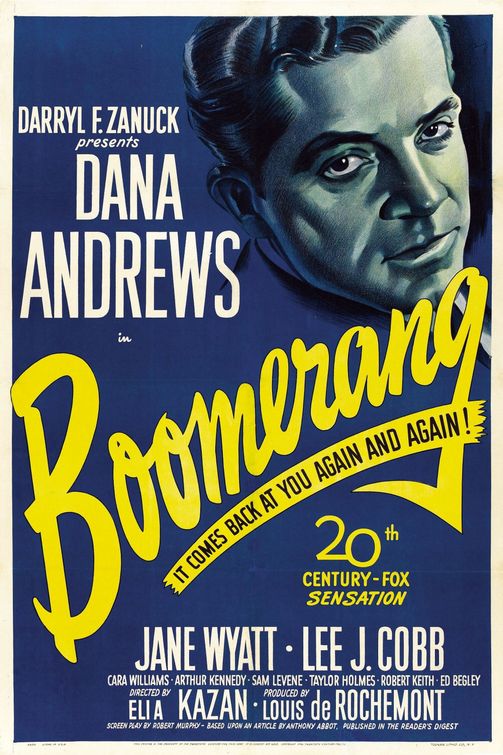

BOOMERANG!

Ivan Shreve over at the ever wise and amusing Thrilling Days Of Yesteryear writes, “The argument over whether or not Boomerang! is a legitimate film noir will rage on until eternity.” Of course it will. Arguments about what films are or are not noir are almost always irrational and thus can never be settled in any reasonable way.

The general idea is to parse any film made in Hollywood in the 1940s and 1950s searching for reasons to call it noir. The use of shadows, the element of crime in the plot, any suggestion of moral ambiguity or darkness in the characters is usually enough to qualify a film for the designation. The truth is that film noir is no longer a descriptive or analytic term but one of approbation — it means “a film which is cool, a film I like”. Sometimes it just means an old film in black-and-white which isn't a comedy or musical.

It would be far more logical to ask a simple question up front — is there some other established genre or tradition into which a particular film fits? If there is, there's no conceivable reason to tag it as a noir. Doing that just makes film noir a term so vague as to have no real meaning at all.

As it happens, Boomerang! fits nicely into a very distinct tradition usually called docu-noir. The tradition was virtually invented by Louis de Rochemont, who happens to be the producer of Boomerang! De Rochemont made his name producing the March Of Time newsreel series, essentially a breezier and more entertaining variant of the standard newsreel. He then became a producer of features at Fox. His first film, the docu-noir The House On 92nd Street, set the pattern for the new form.

Docu-noirs were police or government-agency (or sometimes newspaper) procedurals, usually based on real events and filmed in a quasi-documentary style, often in the locations where the real events occurred. Although they dealt with the same post-war anxieties that fueled the classic films noirs, they were radically different kinds of films, because they took the point of view of the authorities and they insisted that the official institutions of society could combat society's ills.

[Caution, plot spoilers ahead . . .]

The protagonist of a docu-noir might encounter corruption within the institution he served, but his personal integrity was always a match for it and allowed him to ensure that justice was done in the end. There was often, as in Boomerang!, a subsidiary character (played by Arthur Kennedy, above, in this case) who resembled the protagonist of a classic noir, an innocent man wrongly accused, dragged down by fate or official misconduct, but we never saw the story through his eyes — we saw it through the eyes of the official (or dogged reporter) who would save him.

There are no such saviors in classic noirs — the whole burden of which is to involve us emotionally in the nightmare of the trapped man, to show us the world from his point of view, to make us feel its oppressive weight. The protagonist of a classic noir might or might not survive his nightmare, but such salvation as he occasionally does find is likely to be provisional — there is rarely any suggestion that the world which generated his nightmare is ever going to change.

This is light years away, existentially, from a film like Boomerang!, where the hero has a dark night of the soul, chooses to do the right thing, defies the corruption of his bosses, frees the innocent man and goes on to become the Attorney General of the United States. It is, in short, a film which questions and criticizes but ultimately vindicates the American legal system, affirming the efficacy and ultimate triumph of moral action within it. If Boomerang! is a film noir then I guess Mr. Smith Goes To Washington is a film noir, too, and we need some other term to describe movies like Detour, Out Of the Past and Thieves Like Us.

CHRISTMAS CIGARETTES

Nothing says “Christmas” like cigarettes — nothing evokes the spirit of the season like an armful of cigarette cartons with gay holiday designs on them . . . and when sexy Ann Sothern delivers them to your door, all you can say is, “Ho, ho, ho!”

[With thanks to the Gunslinger for the image.]

BARNUM

The 19th-Century showman P. T. Barnum is probably best known today for the circus which bears his name — the only one of the great American circuses to survive into the 21st Century — and for a line he never spoke, “There's a sucker born every minute.”

Barnum didn't see his public as suckers but as citizens of a grand republic in desperate need of cheering up. Though a religious man himself, a teetotaler and (eventually) an abolitionist, he carried a life-long resentment against the dour form of religion he grew up with in his native Connecticut. He believed that America's spiritual well-being depended on regular relief from the grim industriousness and fun-killing morality of its Puritan roots — and this he set about providing with an energy and inventiveness that still boggles the mind. In the annals of American show business, only Walt Disney comes close to being a comparable figure — and Barnum built his entertainment empire in an age when newspapers and handbills were the only mass media available to advertise his spectacles.

Barnum perpetrated hoaxes, to be sure, but never too seriously — he paid journalists to question their authenticity as a way of drumming up interest in them. He knew that people enjoy being fooled, if the foolery is entertaining enough. He had a passionate belief in the necessity of giving the public good value for its entertainment dollar, and humbug, if it's spectacular enough and outrageous enough, is always fun.

Though Barnum sponsored touring shows and circuses, the heart of his empire was the American Museum, securely anchored in downtown Manhattan. There had never been anything quite like it — part art gallery, part museum of natural history, part zoo, part carnival midway, part theater. It housed respectable paintings and sculptures, wax figures of famous people, miniature models of exotic cities and structures, human skeletons, mummies, gemstones, historical artifacts (real and bogus), fossils, stuffed and live animals and ever-changing exhibits of human “freaks”.

In addition to all this the museum hosted one of the largest theaters in New York, with its own repertory company, presenting plays (advertised as dramatized “lectures” to skirt the city's strict theatrical regulations) and variety acts, everything from ballet dancing to blackface minstrelsy.

You could say that Barnum in his museum spent his life bringing together things that the official culture of the 20th Century, spurred on by increasing specialization within the academy, did its best to separate into distinct categories and distinct venues. Art belonged in art galleries and art museums, stuffed animals belonged in natural history museums, live animals belonged in zoos, freaks and hoaxes belonged in carnival sideshows (if they belonged anywhere), dramas and variety shows belonged in specialized theaters located in theater districts.

In many ways Barnum's museum was a better and more inspiring reflection of real culture than our ghetto-ized entertainment scene — and I think you could make a case that the Internet is allowing Barnum's vision to have a rebirth in the culture of the 21st century. Boing Boing, for example, calls itself a directory of wonderful things — which is just a virtual version of Barnum's “showcase of wonders”. A blog like Tom Sutpen's If Charlie Parker Was A Gunslinger tries to open a window on visual culture with no preconceived intellectual firewalls between categories of images — and thus reflects the way we actually experience visual culture. In its own small way, this blog, partly inspired by Sutpen's enterprise, tries to do the same thing.

So Barnum is back — or perhaps he never really left, since we have always seen and experienced the world of “curiosities”, of “wonders”, of “entertainments”, of “art” the way Barnum did, as a jumble, a continuum, a conversation between different kinds of things. Now, that conversation has emerged into the light again in virtual space, as it once existed in the physical space of Barnum's museum . . . and as it exists in the physical spaces of Las Vegas, too, if you want to go there — and let's face it, almost everybody does, whether they admit it or not.

SOME CHRISTMAS PRESENTS FROM GIL ELVGREN

Do not open until 25 December!

IN THE CHRISTMAS SPIRIT

Over at the Hard Rock Casino the cocktail waitresses have started wearing their cute little Christmas costumes, very similar to the outfit worn above by Stephanie Sadorra, Las Vegas model and poker player, who was spotted recently at the Hard Rock poker room.

One of the female dealers in the room also wears a similar costume, with fingernails painted green for an extra festive touch, but she says the outfit is uncomfortable because it's made of polyester and doesn't breathe.

Men rarely appreciate what women go though in order to achieve cuteness.

THE END OF ENGLIGH

Dr. Drew Casper is the Alfred and Alma Hitchcock Professor Of American Film at the University of Southern California. He is a published author on film. I assume that the “Dr.” in front of his name means that he has a PhD. Casper shows up often delivering “expert commentary” on DVDs. I assume that he speaks English as a first language but somehow in his journey through academia he has not managed to master the rudiments of his native tongue.

His style of speaking involves a lot of rephrasing, designed, I suppose, to suggest the addition of nuance to the points he's making but adding up only to redundancy. In his commentary on the recent DVD release of Notorious, for example, he says that Alicia “is out of control — she has lost control.” These two phrases mean exactly the same thing — one or the other would have served perfectly well. He refers to the famous key in the film as “a prop — an object, if you want.” Yes, I will accept that a prop is an object, since a prop is always an object. It's sort of like saying, “a person — a human being, if you want.” This is a form of pretentious bloviation.

Casper misspeaks constantly in his commentary. He says that Alex's mother “yields a lot of power” in Alex's home, when he means that she wields a lot of power. Of a traveling shot close on Alicia and Devlin, Casper says it suggests that they are “floating on air, existing gravity.” I'm not even sure what he actually meant to say there — “resisting gravity”? Who knows?

Casper introduces the subject of Russian Constructivism and then goes on to refer to it more than once as Roman Contructivism, whatever that might be. Casper also misuses language freely. He says that German filmmakers “triumphed” the use of lighting as an expressive tool. He doesn't seem to know or care that “triumph” is an intransitive and never a transitive verb.

The professor is promiscuously careless about details as well. He refers to the German director “D. W. Pabst”. He says at one point that Alex is taller than Alicia, when he's just been talking about the significance of him being shorter. He says that in Hitchcock's films special effects are always in the service of technique, when he means always in the service of story or character.

Is there no editor or director present when Casper records his commentaries? Doesn't Casper, or someone, listen to them after they're recorded to catch mistakes and suggest retakes? Or is it the case that any old nonsense from the mouth of a man with a PhD is assumed to be authoritative?

Casper is not an idiot — he has many interesting things to say about the themes and strategies of Notorious — but he seems to feel no obligation whatsoever to present his analysis with even a modicum of intellectual rigor or discipline. If Hitchcock had had the same attitude about filmmaking that Casper has about film criticism, we wouldn't be watching Hitchcock's films today. Bloviating about them in such a scatter-brained way is a kind of insult to Hitchcock's professionalism.

Casper's poor language skills offer a terrifying insight into the modern academy, and modern academic standards in the area of film studies. Presumably Casper doesn't fear that his students will note, much less correct, his mangling of English, though some of them would undoubtedly be capable of doing so. They want good grades from him, after all. Presumably, as the occupant of an endowed chair at his university, probably a tenured position, he doesn't fear the criticism of his fellow professors or supervisors, who would have a very hard time removing him from his job. Perhaps they feel that since film is a visual medium, there's no need to speak about it in precise and correct language.

It's all very depressing. When a professor at a major American university can get away with such shoddy speech, it's no wonder that American institutions of higher learning are turning out graduates who are semi-literate, who not only speak but think sloppily about film, among other things.

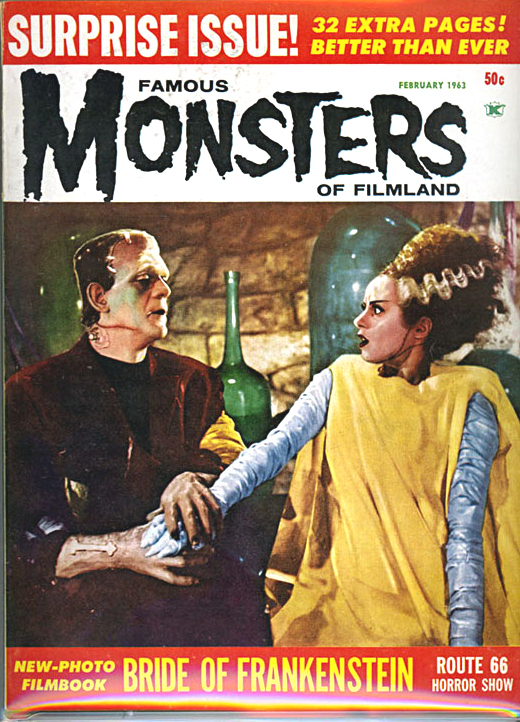

LET US NOW PRAISE FAMOUS MONSTERS

Forrest J. Ackerman died last Thursday, at the age of 92. For anyone who knew his name when they were 12 or 13 or 14, the news comes like the news of Queen Victoria's passing to residents of the British Empire in 1901. Ackerman presided over an empire of the imagination every bit as grand as Victoria's realm, and far more benign. He was the editor of Famous Monsters Of Filmland, the sci-fi and horror movie fan magazine around which a generation of buffs rallied during their formative years. It was a half-silly, half-serious publication devoted to the whole range and the whole history of fantasy on film. It helped to create and validate the community of kids who loved film of this sort, and gave them permission to take it seriously.

Famous Monsters was single-handedly responsible for focusing my own love of movies. It opened my eyes to silent film, because there were, after all, silent monster movies, and to other kinds of film. When I was 12 I started buying books about the history of movies just for their monster movie content and ended up enthralled by every kind of movie.

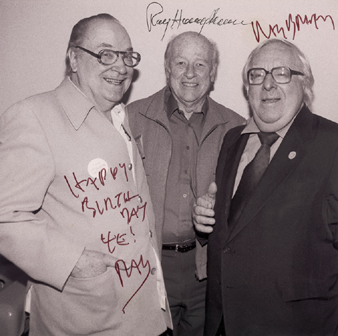

In seventh grade I met two fellow students who were secret fans of the magazine and introduced me to it — within months we were making our own 8mm monster movies. The three of us attended a science fiction convention in Washington, D. C. in the early Sixties where we actually met Forrest J. Ackerman (seen above, on the left, with Ray Harryhausen and Ray Bradbury.) He took us out to lunch. He took us and our interest in monster movies seriously. All of us, now in our fifties, are still fanatics of the kind of movies “Forry” loved.

Such stories could be repeated endlessly. Joe Dante, John Landis and Steven Spielberg were all fans of the magazine when they were kids. In later life, Spielberg autographed a

poster of Close Encounters of the Third Kind for Ackerman, writing, “A

generation of fantasy lovers thank you for raising us so well.”

And so we all do — now and forever.

A CALENDAR GIRL FOR DECEMBER

Hello, Santa . . .

[By Al Moore for Esquire, 1950]

POKER AND PORN

Last night Jae I played a little poker at Planet Hollywood, without much luck. At my table there was an extremely beautiful young woman, who played with a sense of fun and daring that was infectious. She had a fresh, innocent quality which was deceiving — she was always playing games, check-raising on draws for example, which is a bold move in a Las Vegas poker room, where people don't mind putting you all-in if they think you're trying to mess with them.

Afterwards Jae said he thought he recognized the woman, and suddenly realized where he'd seen her before — in a porn movie, where she performed sex acts for pay under the name of Jenni Lee. She's now “gone legit” and works as a model and professional poker player here in Las Vegas under her real name Stephanie Sadorra. She's just 26. Odd to move from porn to poker, where preserving your mystery is a key to winning. On the other hand, she did bet heavily and make people pay to see her cards, which is also a key to winning.

There are many cute female poker players here in Las Vegas who dress provocatively, showing lots of cleavage, and flirt ostentatiously to distract men and put them off their game. Ms. Sadorra wasn't that sort. She was dressed modestly and paid personal attention only to her boyfriend, who was playing at a nearby table. She looked more like the All-American girl in the photo at the head of this post (from her MySpace page) than like the provocative glamor girl gazing at herself in the mirror above.

Poker is a game where it's easy to leave your past behind in the intense concentration of excitement occasioned by each new fall of the cards. That's part of the intoxication of gambling, which, as Walter Benjamin once observed, obliterates time. I wonder if Ms. Sadorra looks at the faces of the people she's playing against and wonders if they've seen her in other contexts and think of her not as a pretty good poker player but as a very pretty ex-pornstar.

STUDIO SNOW

Next to real snow, there's nothing quite as lovely as studio snow in black-and-white films from Hollywood's Golden age.

shahn, at the ever-magical six martinis and the seventh art, is an aficionada of bogus blizzards on film and has posted some screen shots of my favorite ersatz snowfall in movies, from Swing Time.

If you live someplace warm, like the middle of the Mojave Desert, fix yourself some egg nog, light a fake fire, gaze through the window of your computer screen and enjoy the prop flakes in cozy comfort. Better still, give Swing Time another spin on your DVD player and watch the imaginary snowflakes fall on Fred and Ginger as they sing and dance their way into your heart one more time.