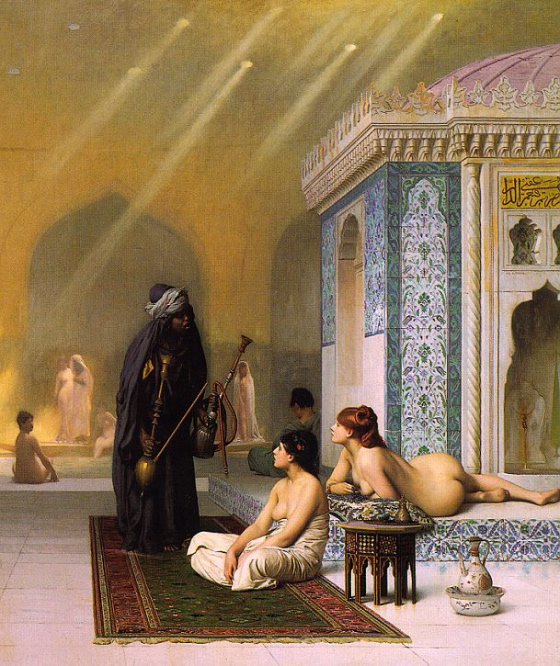

This wonderful portrait, Carmen Of Cordova,

is by Julio Romero de Torres, a Spanish painter of the late Victorian

and early modern eras. His images are dark, earthy and

erotic, with a hint of the perverse.

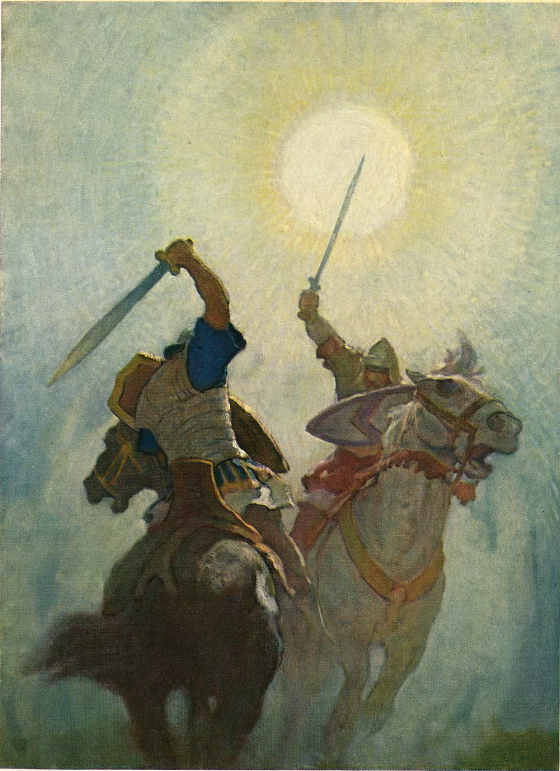

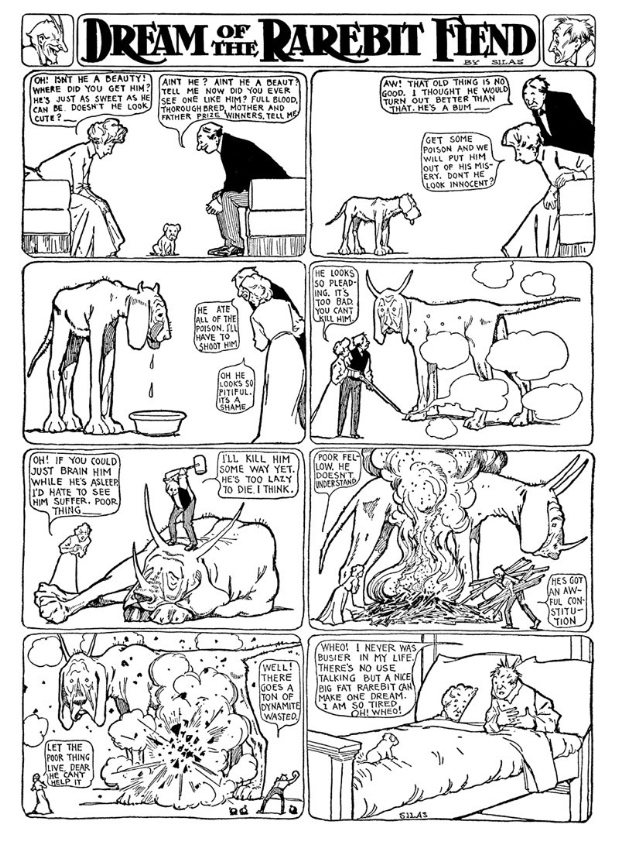

He started out doing conventional Victorian narrative tableaux, like the one above — titled Look How Beautiful She Was! — but eventually developed a more eccentric vision. Below, a twist on a famous paiting by Velasquez:

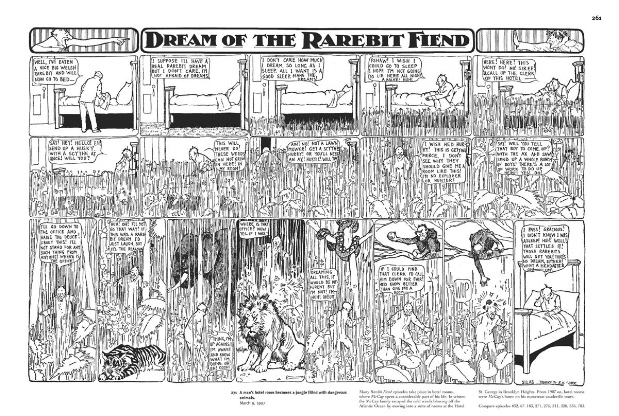

Like any respectable Spaniard he both loved and feared women . . .

. . . and also tended to see them in a mystical light:

His sensibility represents an odd blend of the carnal and the spiritual

— always in his work, however sensual, we can hear the Spanish saying

“Where the body goes, there goes death.”

Above, the artist in his studio with a model and a visitor.

Romero de Torres was born and spent most of his life in Córdoba, taking

time out to serve as a pilot in WWI and to visit the Argentine, where

he got sick, returning to Córdoba to die at the age of 55. There

are no books in English which collect his work, although twelve more

books about the mildly amusing advertising artist Andy Warhol were

published last week.

Something is terribly wrong with our civilization — but you knew that.

There is a museum in Córdoba which lovingly preserves his house and work, which you can visit virtually here.

Thanks, as so often, to Little Hokum Rag and Femme Femme Femme for pointing the way to this enchanting painter.