Follow this link for the fifth in a series of essays in honor of André Bazin . . .

Follow this link for the fifth in a series of essays in honor of André Bazin . . .

This is the fifth in a series of essays in honor of André Bazin.

Irving

Biederman, a

neuroscientist at the University of Southern California, has conducted

experiments in the evolutionary and biological basis of the human need

for information. It would seem that the human brain is to a

certain extent programmed to acquire information, especially about the immediate physical environment — logical enough since

such information, about sources of sustenance and about external

threats, would be crucial to the survival of the species.

Lee Gomes, writing in The Wall Street Journal (linked on Boing Boing), reports this about Biederman's research:

Dr. Biederman first showed a collection of photographs to volunteer

test subjects, and found they said they preferred certain kinds of

pictures (monkeys in a tree or a group of houses along a river) over

others (an empty parking lot or a pile of old paint cans).

The preferred pictures had certain common features, including a

good vantage on a landscape and an element of mystery. In one way or

another, said Dr. Biederman, they all presented new information that

somehow needed to be interpreted.

When he hooked up volunteers to a brain-scanning machine, the

preferred pictures were shown to generate much more brain activity than

the unpreferred shots. While researchers don't yet know what exactly

these brain scans signify, a likely possibility involves increased

production of the brain's pleasure-enhancing neurotransmitters called

opioids.

“A

good vantage on a landscape and an element of mystery” strike me as

qualities of all powerful cinematic images — providing we expand the

word landscape to include interior spaces. “A good vantage”

implies sufficient clues to read the space of the environment

represented, while “an element of mystery” implies an image that is

complex, that doesn't yield up its information too quickly, that

requires investigation.

A cinematic image whose primary function is to deliver narrative

information, as opposed to a spatial illusion, is not going to engage

our imagination in a powerful way. A cut between two

informational images whose primary function is to establish another

piece of information is likewise not going to be deeply

satisfying. An example of this would be a cut between a close-up

of a woman looking at something and a close-up of what she's looking

at. If the two shots in question were not themselves

intrinsically engaging, the relationship between them would be purely

narrative, purely expository. The shot of the woman looking at

something would not create genuine mystery, only an informational

question — and once the question was answered (by the close-up representing her POV) the interest of the

images would be exhausted.

There might be meta-cinematic qualities to the two images — if the

woman turned out to be looking at a knife, we might wonder what role

the knife will play in the story — but this would not reflect on the

essentially cinematic qualities of the images.

In all this, of course, I am simply recapitulating André Bazin's theory

of the role of montage in cinema, but I think Biederman's research

offers a psychological support to Bazin's thinking. The

deep-focus shots of Welles and Ford, the long scenes that play out

without directing our attention to specific elements through editing,

give us both “good vantage” and “mystery” — they engage deep levels of

consciousness that seem to be fundamental to human perception.

And, like Biederman's “preferred images”, they create a pleasure that

may well have a pre-programmed neurological basis.

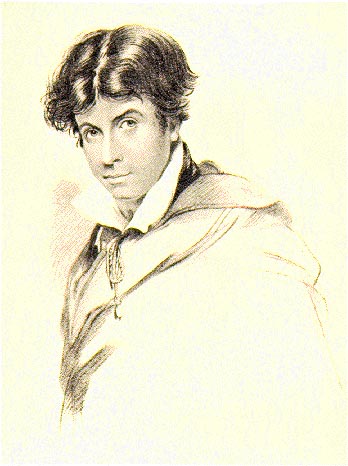

The poem, called Rondeau, was written by Leigh Hunt (pictured above) and first published in 1838. Hunt was a minor literary figure of the Victorian era, a friend of Shelley and Keats and Dickens. His poetry has a simplicity that can make it seem trivial, but I think Rondeau is perfect. It's music allows its simplicity to breathe, and reminds us of that sincerity of unselfconscious sentiment which the Victorians at their best could summon — a sincerity which 20th century literature, charting the age of irony, completely lost touch with. Virginia Woolf, early in the century, lamented the loss, distressed that poets could no longer write lines like these, by Christina Rossetti:

My heart is like a singing bird

Whose nest is in a watered shoot;

My heart is like an apple tree

Whose boughs are bent with thickset fruit;

My heart is like a rainbow shell

That paddles in a purple sea;

My heart is gladder than all these

Because my love is come to me.

Such directness of feeling did survive in the popular arts, in pop songs and in the movies — any place where the arbiters of high culture had no influence.

Most improbably, Orson Welles recited Rondeau at the close of a pilot for a TV talk show he made towards the end of his life (which wasn't picked up.) Welles was an unregenerate Victorian, which was a source of much of his secret power, and almost all of his films deal with loss, with the memory of some sweet, unrecoverable moment in time that haunts the present . . . a characteristic Victorian theme.

Rosebud, Mr. Bernstein's girl on the ferry, the Amberson's ball, a long-past love affair with the Baroness Nagel in Warsaw, the chimes at midnight . . . all these are one with Jenny's kiss.

Leigh Hunt wrote, “Every one should plant a tree who can. It is one of the cheapest . . . as well as easiest, of all tasks.” Trees, said Hunt, “are green footsteps of our existence, which show that we have not lived in vain.”

Rondeau is such a tree.

Jimmy

Giuffre died last month, at the age of 86 — I just heard about it. Giuffre was a

jazz clarinetist with a cool, mellow style, influenced by Lester Young. He was a fixture of the laid-back West Coast jazz scene in the 50s

and 60s and I was lucky enough to hear him play once in the 60s at my

boarding school in New England where he and his small group (a trio, I

think it was) were hired for one of our rare entertainment

treats. I can't imagine how that happened — I never identified

anybody on our faculty who had a passion for jazz — but I'm sure glad

I got to hear the cat blow in person.

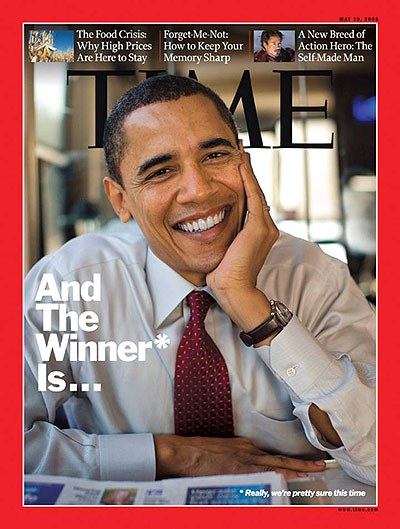

Assuming that Hillary Clinton can't lead the Democratic Party and the

rest of the country into Bizarro World, there's a good chance that

Barack Obama will be the next President of the United States. By

my reckoning, that would make him only the fourth cool President in our

history.

A genuinely cool President has to be someone who would be cool even if

he or she wasn't President, someone you'd think it would be cool to

hang out with in a situation that had nothing to do with

politics. That leaves us with Thomas Jefferson, Theodore

Roosevelt and John Kennedy. Kennedy makes the list by the skin of

his teeth, since it would only be cool to hang out with him somewhere

like Las Vegas or Hollywood, and only if you were in serious party mode

and relatively drunk. You'd have to be able to forget that he was

a married man with two small children. (Bill Clinton was cool in

a similar sort of way, but only if you grew up on a farm and met him on

a rare visit to a roadhouse on a rocking Saturday night.)

Jefferson and Kennedy were sexual creeps, so Obama would be only the

second cool President who was also a decent human being in his private

life.

How cool is that?

I don't know how to translate the title of the above painting by Julio Romero de Torres — every possible rendition of ¡Viva el Pelo! into English sounds silly — but el pelo

means the hair, so you get the idea. The image reminds me of a line by the poet Robert

Duncan, “in the dark of the moon the hair rules”. This in turn

reminds me of something the poet Robert Browning said about his wife

Elizabeth Barrett Browning after her death, when he was asked what it

was like being married to such a famous person (she was far more famous

than he was during her lifetime.) Yes, she was known to the

world, Browning admitted, “but I knew her on the dark side of the moon” —

the side of the moon the world never sees . . . where the hair rules.

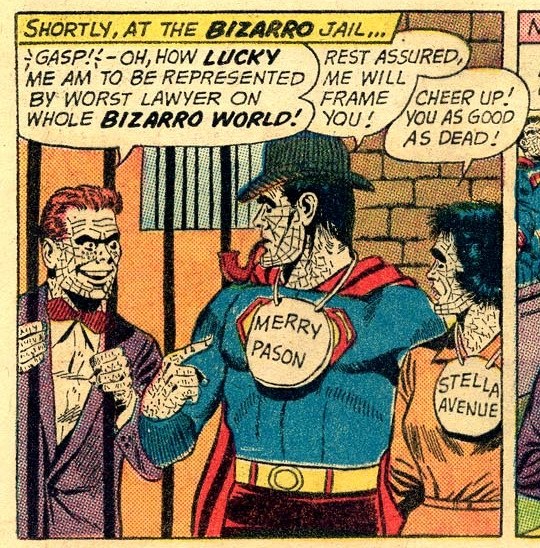

Today, Hillary Clinton argued that in Bizarro World, she would now be

the undisputed nominee of the Democratic party. “In Bizarro

World,” she explained, “the candidate receiving the least number of

votes in an election is the winner. Superman and Lois Lane are

also husband and wife in Bizarro World. I think everybody wants

to see those two hook up — in Bizarro World, it’s a done deal.

As president of Bizarro World, I’ll be ready to hit the ground running

amidst heavy sniper fire. In Bizarro World, my campaign has

loaned me eleven million dollars. In Bizarro World, I’m the transformative black candidate

and Barack Obama is the cynical white woman in a pants suit.”

Clinton added, “I urge all unpledged superdelegates to join me in

Bizarro World — or, as it’s affectionately known to millions around

the world, Washington, D. C.”

Follow this link for the fourth in a series of essays in honor of André Bazin . . .

The fourth in a series of essays in honor of André Bazin . . .

André

Bazin was exhilarated by the idea of a cinema grounded in photographic

images that conjured up an intense illusion of space. He saw this

as the center of cinema's power. Montage, he believed, created

only secondary and less powerful effects, merely intellectual and

therefore not as profound. Cutting between shots of a single

location could create a mental impression of the space of the location

but not a visceral sense of experiencing that space first-hand.

“Metaphorical montage”, cutting between images to create a conceptual

relationship between them — as between a shot of a kiss and a shot of

fireworks going off — he saw as equally “intellectual” and thus

equally secondary. Cutting, he believed, tended to undermine the

power of cinema to imaginatively, as opposed to rationally, engage us.

He was on to a signal truth here, but there are some problems with his

argument. He consistently identified cinema's spatial illusion

with realism, and saw that realism, the shared ontological identity of

an actual space and its photographic record, as crucial to cinema's

power. However, as I've argued before, this fails to account for

the cinematic power of hand-drawn or computer-generated images, both of

which can create impressions of spaces which can engage us

imaginatively just as powerfully as photographic images.

Consider also the realm of dreams. We often in dreams enter

spaces which have no correlative in the waking world — a new wing of

our house, for example, which seems just as real as the house we know

in waking life. The impression of “reality” here does not depend

on any shared ontological identity between the imaginary wing and our

dream experience of it. The mechanical authority of the camera

does not figure into the equation, and yet the imaginary wing feels

just as real as the spaces of waking reality. Our dreaming mind

convinces us of this reality without any forensic corroboration.

It is the impression of space alone which links photographed cinema

with animated cinema. Photography and animation are merely

techniques for creating illusions of space which we can imaginatively

enter as wholly and as confidently as we enter the spaces of dreams.

Bazin argues that shots need to convey a sufficient impression of

“realism” to counteract the enervating tendency of montage, which

again is a profound insight, but fails to account fully for the dual

nature of some “metaphorical” editing. When Hitchcock cuts from a

shot of Cary Grant and Eve Marie Saint embracing on the train at the

end of North By Northwest to

a shot of the train entering a tunnel, the intellectual aspect of the

visual pun is clear enough — but both shots are interesting and

powerful plastically, both deliver a visceral impact, so that we can

not only comprehend the meaning of the shot of the train rationally

(as a pun) but also feel it as a physical evocation of intercourse.

Finally, Bazin's evaluation of montage does not fully take into account

the musical effects which editing can create. I would agree with

Bazin that such effects only have true power when the images involved

have an intrinsic plastic power of their own. We have all seen

those “experimental films” in which indifferent images are cut to the

rhythms of a piece of music — their effect is thin, superficial, the

correspondences between the rhythms of the music and the rhythms of the

editing merely mechanical, an exercise in redundancy.

But consider the musical rhythms of the editing in Orson Welles' Falstaff.

The images, however fleeting, are always powerful plastically,

viscerally evoking space, but the editing gives them a new musical

quality — much the way the rhythms of poetic meter confer a

meta-meaning above and beyond the literal meaning of the poet's words.

My arguments with Bazin here are narrow but important, I believe.

If I were speaking with him today, face to face, as I sometimes feel I

actually am, so vivid is his presence in his writing, I would urge him

to cut loose from his attachment to photographic “realism” and

concentrate on the imaginative uses of all illusory space in cinema,

however it's achieved, and to think again about the ways illusory space

can be enlisted in the service of montage, not just as a kind of

compensation for the intellectual reductionism of montage but as a way

of investing montage with an über-cinematic artistic capacity all its

own.

John

Farrow wasn't by any means a great director but he was a very

interesting man and he made some very interesting movies. A devoted

Catholic and a serious student of Catholicism — he wrote a book about

the history of the Popes — he was also known as a mean son-of-a-bitch

on the set who liked to bully his actors and crew. After shooting

wrapped on California (above), star Barbara Stanwyck demanded that he make a public apology to everyone who worked on the production.

On the other hand, she gives a terrific performance in California,

way better than the mediocre script deserves, and the film is filled

with surprising passages, notably a number of extremely long and

complicated scenes played out in single takes with extensive camera

moves. None of these, however, is framed or choreographed

dynamically, so they don't have the excitement of the long takes found

in the films of Welles or Renoir.

California doesn't have a

coherent tone in any respect. It has odd, grandiose montages with

opera-like chorales playing under them, and conventional Western

musical interludes in which characters sing improbably. The

gritty, sexy frontier hustler created by Stanwyck seems to be from

another movie.

Farrow didn't seem to have a good feel for genre or for script. Plunder Of the Sun (above), filmed entirely, and very evocatively, on location in Mexico has one of the most stylish and promising film noir

openings ever concocted, but the story just dribbles away, turns into a

conventional treasure-quest adventure. Again, a superb central

performance — this time by Glenn Ford, tense with understated despair

— is wasted.

Still, there's usually something in a John Farrow movie worth paying

close attention to — some flight of inspiration that redeems the

clunkiest programmer. He had a kind of ambition, a kind of

vision, but it seems to have come to him in fits and starts.

Maybe the frustration of that was the source of his on-set rages.

In a previous post about Orson Welles's ill-fated Brazilian film It's All True

I mentioned that Welles came to see the history of the samba as the key

to Brazilian culture. I wondered if there might be a CD

collection that showcased that history. Of course there was, and

of course it was French — the French having a knack for combining

passion about American music with a logical approach to presenting it.

Fremeaux & Associates offers several historical surveys of

Brazilian music which give a good idea of what Welles found when he

visited the country in 1942. The one above surveys the samba

alone, which originated around 1917 as music for the Carnival and

eventually became a highly commercialized form of dance music

throughout the Americas in the 1940s.

The great revelation of this set is Carmen Miranda in her pre-Hollywood

days. Before she became a musical comedy star, famous for her

tall fruit-basket hats (“Bananas is my business!”), she was one of the

musical treasures of Rio — a terrific and very sexy singer.

But samba, as it turns out, is just the rio

into which all streams of Brazilian music flow. The oldest style

it incorporates is choro, an instrumental form meant for listening, not

dancing. It usually features ornate flute lines accompanied by

various stringed instruments. It started out very European in

sound, with African rhythms adding flavor, but later became a bit more

rambunctious. Its evolutions are charted in the collection

illustrated above.

Other subsets include brass marching-band compositions and various

regional styles, many of which are charted in the Fremeaux

&

Associates collection above. Fremeaux offers a couple of other

historical surveys, but these three will give you a comprehensive

picture of Brazilian music in the first half of the 20th Century.

The pleasures they deliver are not primarily scholarly, however.

There's hardly a song on any of the two-disc sets which is less than marvelous, and all of them

will set you either dreaming or dancing. (The imported sets can

be found on Amazon, most cheaply through their Amazon Marketplace

sellers.)

Listening to these CDs you'll see right away what so enchanted Welles

back in 1942 and grieve anew that he never got a chance to finish his

film about Brazil and the samba.

This wonderful portrait, Carmen Of Cordova,

is by Julio Romero de Torres, a Spanish painter of the late Victorian

and early modern eras. His images are dark, earthy and

erotic, with a hint of the perverse.

He started out doing conventional Victorian narrative tableaux, like the one above — titled Look How Beautiful She Was! — but eventually developed a more eccentric vision. Below, a twist on a famous paiting by Velasquez:

Like any respectable Spaniard he both loved and feared women . . .

. . . and also tended to see them in a mystical light:

His sensibility represents an odd blend of the carnal and the spiritual

— always in his work, however sensual, we can hear the Spanish saying

“Where the body goes, there goes death.”

Above, the artist in his studio with a model and a visitor.

Romero de Torres was born and spent most of his life in Córdoba, taking

time out to serve as a pilot in WWI and to visit the Argentine, where

he got sick, returning to Córdoba to die at the age of 55. There

are no books in English which collect his work, although twelve more

books about the mildly amusing advertising artist Andy Warhol were

published last week.

Something is terribly wrong with our civilization — but you knew that.

There is a museum in Córdoba which lovingly preserves his house and work, which you can visit virtually here.

Thanks, as so often, to Little Hokum Rag and Femme Femme Femme for pointing the way to this enchanting painter.

Jean-Luc

Godard once observed that, with the passing of time, the fantasy films

of Georges Méliès have become actualities, now that man has in fact

made a voyage to the moon, while the actualities of the Lumière

Brothers have become fantasies, since they record lost worlds to which

we can never return, as mythological now as Oz.

I thought of this while watching Electric Edwardians,

the Milestone DVD of Mitchell & Kenyon actualities of Edwardian

Britain. I must say I was blown away. It's the most

gorgeous collection of cinematic images outside of Intolerance or Sunrise or Welles's Falstaff, lyrical and deeply moving.

With the

possible exception of a few infants who lived to a great age, all the

people in these films are dead. As a commentator on the DVD

observes, the young boys in the films were part of a generation that

would be swept into oblivion long before their time by the mass carnage

of the Great War a decade or so later. The bustling street life

that most attracted Mitchell & Kenyon becomes for us now a memento

mori, incredibly sweet and sad.

I can't imagine

that anyone who loves movies and owns a DVD player wouldn't want to

have this DVD and to watch the films on it over and over again.

They may constitute a kind of unconscious art, but it's art of a very

high order.

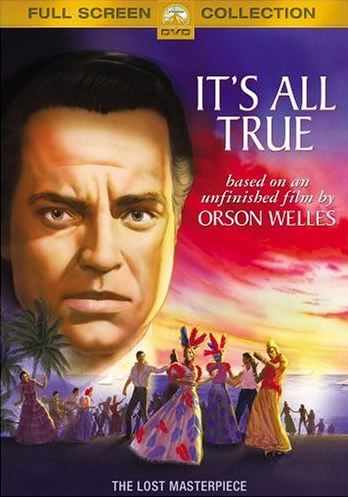

In 1942, right after he finished principal photography on his second film, The Magnificent Ambersons,

but before editing on it began, Orson Welles headed off to make a film

in Brazil promoting inter-American friendship. America was at war

and Welles had been convinced by the government that it was his

patriotic duty to undertake this assignment, designed to keep our

neighbors to the south from drifting into the sphere of Axis influence.

Welles, exempted from military service by various ailments, could

hardly have refused. He planned to make an omnibus film mixing

fictional and documentary episodes

— a kind of essay on aspects of South American culture. He fell

in love with Brazil and groped his way slowly towards a form in which

to convey what he found there, finally settling on the history of the

samba as a key to the society.

His groping frustrated his corporate masters at RKO back in

Hollywood. They were also worried that much of his documentary

footage of Carnival and the samba clubs of Rio showed what they called

“jigaboos” mixing and dancing with white people. It was precisely

this racial diversity that Welles admired in the Brazilian culture.

Eventually RKO pulled the plug on the project. Welles was left

with one camera, no sound equipment, 40,000 feet of black-and-white

film and $10,000. Hoping to salvage something from the adventure,

he headed north to what was then the small coastal village of Fortaleza (below) to make a documentary-like reconstruction of a

legendary event in recent Brazilian history — the 1500-mile voyage of

four fisherman on a crude sailing raft to present grievances to the

government in Rio.

The voyage made the four men national heroes, and they were received by

Brazil's strongman leader, a sort of populist dictator, who granted the

substance of their demands.

Welles shot most of the footage he needed for this film-within-a-film,

but was never allowed to edit it. After his death, the footage

was assembled into something presentable and included in a documentary

about Welles' ill-fated Brazilian project. The documentary is now

available on DVD:

The episode of the four fishermen, even crudely reconstructed, is

simply stunning. It may be the most beautiful semi-documentary

ever made. Eisenstein's very similar project, done in Mexico a

decade earlier, ¡Que Viva Mexico!, looks like static fashion photography by comparison. Four Men On A Raft, as Welles called the episode, also blows away the semi-documentaries of Robert Flaherty (like Nanook Of the North) and Michael Powell (The Edge Of the World.)

Welles's images are dynamic, lyrical, full of movement and yet also

convey a convincing documentary feel. They are cinematic poetry

of the highest order.

Simon Callow, in his multi-volume biography of Welles, says that if

Welles had shot nothing else in his life but this footage he would have

to be recognized as one of the supreme masters of cinema. This is

true.

While Welles was creating this miracle in Brazil, the executives at

RKO, with the aid of some of Welles' most trusted associates, were busy

mutilating The Magnificent Ambersons.

They blamed the collapse of the South American film on Welles's

procrastination and extravagance, even though he had not exceeded the

project's budget at the time it was scrapped. The vandalism of Ambersons

had a vindictive quality to it, to judge by internal RKO correspondence

on the subject, and the myth of Welles as an irresponsible artist,

created by RKO to justify its actions, which included the dismantling

of Welles' production unit at RKO, haunted him for the rest of his life.

RKO made a point of destroying the footage they cut from Ambersons, although Hollywood figures like David O. Selznick begged them to preserve it, but the It's All True footage somehow survived. It includes ravishing Technicolor sequences shot in Rio, some of which can be seen in the It's All True documentary . . . and the material for Four Men On A Raft. (The color images above are not from the film.)

Do

yourself a favor sometime and have a look at the material on the DVD —

unfinished as it is, it's still one of the treasures of 20th-Century

art.