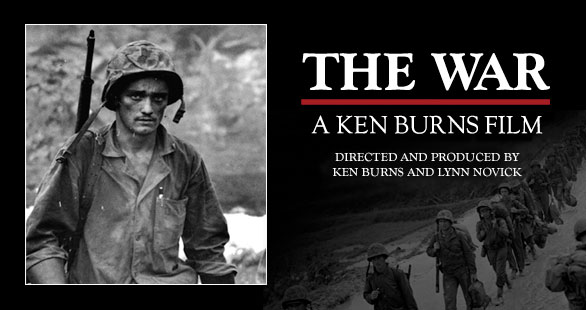

Jae

and I headed back to Death Valley Junction from our dinner at the

Longstreet Casino coffee shop with plenty of time to spare before the

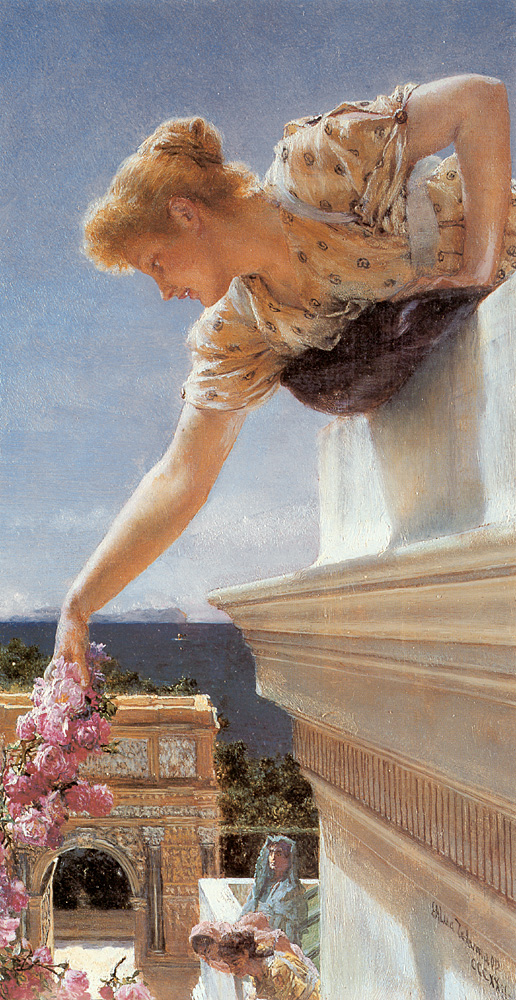

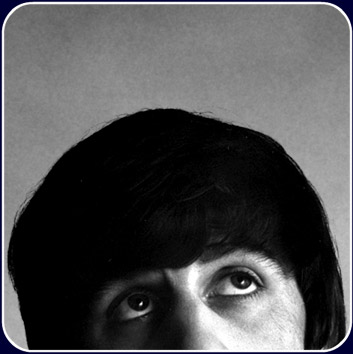

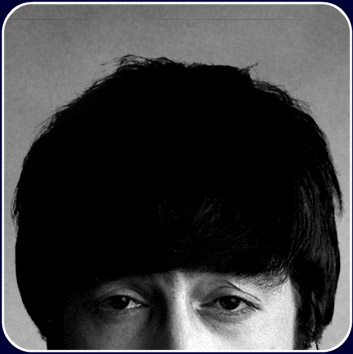

performance by Marta Becket (above) at her Amargosa Opera House.

We were amazed at all the people who'd showed up — the little theater

could hold about a hundred people and it ended up nearly full.

The place is a hoot — all its walls and ceiling painted by Marta

herself to resemble the inside of a Baroque opera house. It took

her four years to complete the job.

Today she is frail and birdlike, but still carries herself as a

dancer. She walks out onstage, sits in a chair and talks and

sings for about an hour. She has great presence, partly

diva-like, partly girlish. You come away from the show, from the

whole phenomenon of the Amargosa Opera House, with a swirl of questions.

Is it silly or sublime to be the biggest star in Death Valley, where there

are no other stars? Is it heroic or preposterous to create your

own world out in the middle of nowhere and dare the rest of the world

to ignore you?

All of the above, I guess. Marta's world is part David Lynch,

part Fellini, part senior high school play, part good old-fashioned

show-biz, utterly disciplined and professional. Once she

bought a ghost town and brought it back to life — now she's a bit of a

ghost herself, but right at home in the spotlight.

What's profound about it all, I think, is the reminder that all theater

deals in the presentation of spirits, not quite flesh and blood, not

quite illusion. She painted an audience for herself on the walls

of her theater, and every Saturday night at 8 o'clock between November

and May she conjures a real audience out of thin air, there on the edge

of Death Valley — she conjures us out of thin air, and we become part

of the ghostly goings-on. We lose some of our solidity in the process and feel

that we know what it's like to dance on air.

[Photos © 2007 Jae Song]