Click on the image to enlarge.

Category Archives: Baja California

BAJA CALIFORNIA SUR

Roadside seafood stand.

CELEBRATING CARLA

In a recent post I noted the 100th birthday of horror movie and Baja California icon Carla Laemmle. Imagine my delight and surprise when I heard from Scott MacQueen, a reader and friend of mardecortesbaja, that he knew the great lady and had hosted her birthday party in his own home, doing the cooking for it himself. (Scott's recipe for Beef Burgundy will appear on this site in the not too distant future, as soon as I have a chance to try it out in the world-famous mardecortesbaja test kitchen.)

Scott also sent along a picture of the festivities, above — with Carla flanked by David Skal (author of Hollywood Gothic) on the left and by Rick Atkins (co-author of Among the Rugged Peaks, Carla's biography) on the right. (Click on the titles of the books to buy them!)

Ms. Laemmle looks — there's just no other word for it — adorable.

CARLA AND RAY

Carla Laemmle recently celebrated her 100th birthday. She was the

niece of Carl Laemmle, founder of Universal Pictures, and she had a

modest career as an actress and dancer in Hollywood. She appeared

uncredited as a ballet chorine in the silent version of The Phantom Of the Opera and had a

bit part in Dracula, speaking the first words in that film as a

passenger in the coach taking Renfield to his fateful rendezvous at the

Borgo Pass. (That's her on the left above, wearing glasses.)

She is now the last surviving cast member from those two iconic horror

films, and thus an icon in her own right for horror movie fans.

She interests me for other reasons, because of her life after the

movies. She became the lifetime companion of Ray Cannon, another

Hollywood professional — actor, writer, director — who left the

business to pursue other ventures.

Cannon became a sports fisherman, supporting himself mainly through

writing about the subject. He was among the first to explore the

fishing possibilities of Baja California, helping to popularize the

peninsula as a fisherman's paradise and a potential tourist Mecca. He

fell in love with it in the late 1940s, before the crowds came, spending

much of each year

there on various fishing expeditions, and eventually wrote the text for

a best-selling picture book about the area, The Sea Of Cortez.

A wonderfully-illustrated collection of his other writings about Baja

California, The Unforgettable Sea Of Cortez, was published recently and

it's a fine evocation of the

peninsula in the days before the tourist boom. Outside the precincts

of Ensenada at the top of it and and Cabo San Lucas at the bottom of

it, Baja California hasn't changed all that much since the time Cannon

discovered it. Over-fishing by commercial interests has depleted the

Mar de Cortes to an alarming degree, but it's still one of the richest

sports fishing spots on earth, and the gracious old city of La Paz has

yet to be despoiled by the California duppies.

The landscapes and seascapes that Ray and Carla loved are still there

— severe and beautiful and brimming with opportunities for adventure.

A SONNET FOR TODAY

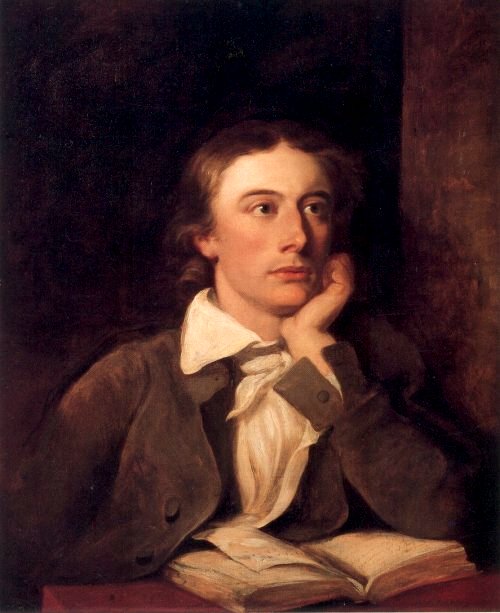

On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer by John Keats:

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific–and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise–

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

Chapman’s Homer seems a bit stodgy today but compared to previous

translations in English it had power and punch — and was much closer

to the supple, hard-hitting Greek of Homer. You have to read

Stanley Lombardo’s bold new translations of Homer to get a sense of how

Chapman’s version must have sounded to Keats’ generation.

The last four lines of this sonnet are what make it memorable, even

though we may know that it was Balboa, above, who first sighted the Pacific

from the vantage point of the New World (in Panama) — not “stout

Cortez”, below.

Hernán Cortés did reach the Pacific coast of Mexico sometime

later, or rather he reached the coast of a sea that communicates with

the Pacific, now called the Gulf Of California or the Sea of Cortez or,

of

course, the Mar de Cortés. This is the great body of water that

lies between the west coast of mainland Mexico and the Baja California

peninsula.

WHAT STAYS, WHAT GETS AWAY

Above

are the fish we took away from our fishing expedition on the Mar de

Cortés — all good for eating. We ate some of the catch in La Paz before

we left, the rest made it, frozen, to Las Vegas and Los Angeles, where

it served for a couple more wonderful meals.

We caught other fish on our expedition — including a few bonito, all

but one of which was thrown back. The biggest of them was saved to

serve as shark bait for a friend of our captain. We caught

several needlefish — nasty looking things with long pointed snouts

which are no good for eating. “Banditos” our captain called them,

disdainfully, because they steal bait. If one got hooked, the

captain had to beat it senseless with a wooden club before he removed the hook, to avoid

having his hands lacerated by the needlefish's sharp teeth.

Nora watched this procedure with burning eyes. “I almost can't

stand to look,” she said. “But it's also kind of exciting.” This struck me as a very Spanish response, with the

appeal of the bullfight in it.

In any fishing tale there's always the part about the one that got away.

Just before we headed back to shore, with our bait almost used up, I

hooked a huge fish. It felt like the big bonito I'd caught

earlier — maybe heavier. It kept wanting to sound and came up

slowly, when I could move it towards the boat, like a massive lead weight at the end of the line. When I got it to

within four or five feet of the surface we could see, in the dappled sunlight rippling through the water, that it was a gigantic

yellowfin tuna. The captain was very excited — this was

a stupendous fish. I was too excited. I jerked the line a

little too hard and the hook slipped out and I watched the amazing

thing swim away again into the depths. I was sad but also oddly

moved by the encounter.

Below, pelicans feed on the remains of our fish, after the captain had filleted them:

After I dropped our catch off at the restaurant at the Los Arcos I went

up to the bar for a beer. I was exhausted from the long drive to

and from the beach and the hours out on the water, all on far too

little sleep. But my nerves were singing. I knew I had

experienced something extraordinary. There was no way I could go

to sleep.

That's the moment I come back to when I think about Baja California —

the way the cold beer tasted, and the image that kept going through my

mind of the big tuna swimming away into the Mar de Cortés, its

silver sides and yellow fins flashing a few times before it disappeared

into the deep blue.

Part of my heart went with it, and is still there — lost at sea.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

DRIVING IN MEXICO: A POSTSCRIPT

I recently came upon a term, “risk homeostasis”, which I think helps explain why driving in Mexico feels safer, and may in fact be safer, than driving in the U. S.

Roads and streets in Mexico tend not to be as well-maintained as they are in the States, lanes tend not to be as well marked (or respected when they are marked), traffic signs are treated very casually — in La Paz, many stop signs are completely obscured by foliage. (You quickly learn to come to a full stop at every bushy tree near the corner of an intersection.)

The result is that Mexicans are forced to drive with greater care, greater attention to the behavior and greater respect for the prerogatives of other drivers — not to mention pedestrians . . . and goats.

In the States, where road and street surfaces tend to be impeccable, lanes are clearly marked, traffic signs prominent and logically placed, livestock properly penned, people rely on these things to allow them to drive more carelessly — while talking on a cell phone, for example, with very little attention given to immediate traffic conditions around the vehicle. They assume that the markings and the rules will keep them out of accidents — but based on that assumption they feel free to expose themselves more to the hazards of unpredictable incidents.

This is “risk homeostasis”, a phenomenon observed in all security systems — people “consume” improvements in security and use them to justify taking more risks.

The result can be paradoxical. Here in the U. S., more pedestrians are killed in clearly marked crosswalks than in unmarked crosswalks — the bright white solid lines give them a false sense of security and lessen their attention to the actual behavior of drivers. (The GPS system in my car, above, has no detailed map data for Mexico — it only told me roughly where I was on the Baja California peninsula . . . all the rest I had to figure out for myself.)

My sister was terrified by the idea of driving in Mexico — because it all looked so anarchic. But it wasn’t anarchic at all — just the opposite. Almost all drivers were following one basic rule, which transcended all the other less basic rules — pay close attention to what your fellow drivers are doing and don’t run into them.

It’s the one basic rule that no improvements in traffic systems can

promote, and that many improvements in traffic systems can actually

undermine. It’s against the law in Mexico to drive while talking on a

cell phone — but it’s something you wouldn’t be likely to do anyway.

You wouldn’t feel safe. You may feel safe driving while talking on a

cell phone in the U. S., but you very likely aren’t.

By directing so much of your attention away from the traffic around

you, you have essentially “consumed” the advantages the U. S. road

system has over the Mexican road system.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

A PLACE FOR PEOPLE

One

of the sweetest aspects of traveling in Mexico is experiencing a

society that has not been thoroughly corporatized. Big U. S.

corporations have infected Mexico on a large scale, but you only see

the manifestation of this in localized areas of big cities — the strip

developments on the outskirts of towns where Wal-Mart and Office Depot

rule. There's a Burger King and an Applebee's on the malecón in La Paz, but they still seem anomalous, like unsightly trash dumps in a vacant lot.

Everywhere else, businesses seem to be run by, stamped

with the personality of, actual human beings. Restaurants and taco stands

are decorated according to the eccentric tastes of the

proprietors. You visit them not to find some standardized form of

service and decor, originating in some distant corporate headquarters,

but to have the adventure of meeting and interacting with the individuals who have personally organized these enterprises.

Las Vegas knows the advantage of this sort of eccentricity —

restaurants here, like casinos, have quirky themes, promise to be

“experiences” . . . but it's all professionally designed, the product

of artful concepts rather than of individual obsessions or

passions. It's better than nothing but it's a far cry from the

organic expressiveness of everyday Mexican culture.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

A FEW MORE TIPS FOR TRAVELING IN MEXICO

In Mexico, when

referring to the U. S. State of California, don't call it California,

call it Alta California, thus showing that you realize there are three

Californias — the U. S. state and the two Mexican states, Baja

California and Baja California Sur. Mexicans are so unaccustomed

to gringos using the term Alta California that they will sometime laugh

when they hear it, but it's a laugh of satisfaction and approval.

I'm sure I don't have to encourage anyone not to refer to Cabo San Lucas as “Cabo”, but by the same token, don't refer to Baja California as Baja. Baja

just means “lower”. It's sort of like saying, “I'm going to

North,” when what you mean is, “I'm going to North Dakota.”

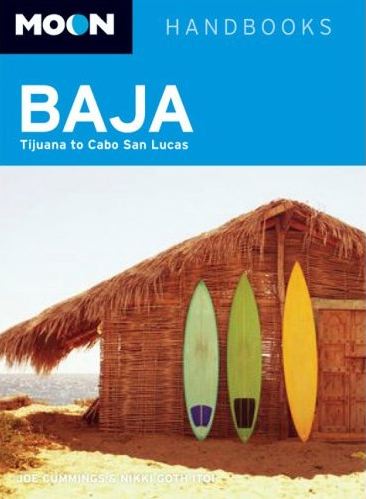

In spite of the above, get hold of a copy Baja in the Moon Handbooks series. It offered the most sensible advice about traveling in Baja California and the most reliable

recommendations about hotels and restaurants. We carried the

2004 edition, which was already outdated in some respects, but there's

a new edition coming out this month (see above.) Also, be sure to

carry the AAA road map of Baja California, the best one available north

of the line.

Take along some chewable Pepto Bismol tablets. These handled all

the (very mild) stomach upsets we suffered in Mexico. Take along

some Benadryl, in case of wasp and bee stings. In the desert

environment of Baja California, bees and wasps will appear out of

nowhere, in the midst of the most barren wasteland, if you expose so

much as cookie crumb, or open a container of anything liquid. If

you keep items made with sugar wrapped and stuff tissue paper into the

tops of open soda or beer containers, they vanish just as quickly.

But accidents can happen. On our fishing expedition, a fellow

passenger in our van popped open a beer when she got back to the beach

after her time on the water. Within about two sips, and without

her realizing it, a bee got into the bottle. She swallowed it and

it stung the inside of her throat on the way down. We were at

least an hour away from any kind of medical facility, and if my sister

hadn't had some liquid Benadryl in her fanny pack, the situation could

have been dangerous. As it was the Benadryl reduced the swelling

in the woman's throat, allowing her to breathe freely, and some Advil

(which my sister was also carrying) helped her manage the excruciating

pain

I have no idea why my sister was carrying Benadryl in her fanny pack —

just as a general precaution, she claimed, though I suspect that

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe put the idea into her head precisely for

the emergency in question.

This brings me to my final tip — always listen to the promptings of La Morenita. She will never steer you wrong.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

MORE TIPS FOR TRAVELING IN MEXICO

First

tip — if you’re a guy, wear a straw cowboy hat. I don’t pretend

to understand the full cultural significance of the straw cowboy hat in

Mexico, but I do know that it has replaced the sombrero as the national

headgear, though it’s not nearly as ubiquitous as the sombrero used to

be. The sombrero has become ceremonial, part of a costume used on

festive occasions and by theatrical mariachi troupes. The bands

of strolling musicians who play in restaurants, for example, wear straw

cowboy hats.

Hip young kids in Mexico don’t wear straw cowboy hats, nor do

sophisticated professionals, and the baseball cap is making strong

inroads everywhere, even in rural areas.

The straw cowboy hat

seems to have something of the significance of the cowboy hat in

America, a sign of solidarity with the nation’s rural roots and the

romance of the ranchero.

The important thing is that Yankee tourists don’t usually wear straw

cowboy hats. My three traveling companions, all blond, were

usually taken at once as Yankees, but people sometimes expressed

surprise to find that I wasn’t Mexican. Even when I was taken as

a gringo, the hat seemed to confer on me the benefit of the doubt,

especially at the ubiquitous army checkpoints where they stop your car

to look for drugs. (They have stepped these up recently at the

urging of the U. S. government, so don’t blame Mexico for the resulting

inconvenience.) We were usually ushered through these with

only the most cursory of inspections, while other gringos were being

searched rigorously. I attribute this to the formal and

respectful greetings I offered to the soldiers — and to the hat.

I live in a U. S. state that still considers itself Western.

Wearing a cowboy hat in Las Vegas doesn’t arouse any special curiosity

outside of the fancy casinos or yuppie enclaves like Summerlin . . . so

I didn’t feel that wearing one in Mexico constituted any kind of

charade. The hat seems to mean more or less the same thing on

both sides of the border. Maybe that’s the point.

Second tip — travel with kids. Mexicans have an instinctive

reaction to kids that instantly dissolves all linguistic and

cultural barriers. They like having them around. They like

you for bringing them around.

Third tip — avoid the Pacific coast of Baja California above

Ensenada. Even if you’re motoring down from San Diego, go east

and cross at Tecate. The Pacific coast above Ensenada offers a

vision of the future of Baja California, as more and more Yankees

retire or build vacation homes there. The vision will make you

ashamed of being a Yankee and depressed about the future of Baja

California.

Fourth tip — go! Just go. Below Ensenada, and outside the

city limits of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico is still there. Its

gracious and humane culture has much to teach and many ways of

enchanting its complacent neighbors north of the border.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

DRIVING IN MEXICO

There's

really no way to explain this precisely, but driving in Mexico is

different from driving in the States. Mexicans don't follow

roadsigns or rules except in the vaguest sort of way — they respond to

the behavior of other drivers. At an intersection with four-way

stop signs, a Mexican driver, if he or she thinks there's time, will

scoot through on the cross street ahead of you without stopping at all

— you are expected to expect this and react accordingly.

Anything is permitted between drivers as long as it makes sense.

It's more like navigating a crowded sidewalk as a pedestrian than

driving on streets and highways north of the border. In other

words, it doesn't work if people aren't instinctively respectful of

other people's space and right of way.

I came to enjoy driving in Mexico very much — it was always an

adventure and always interesting, because it required you to pay

attention to other drivers, to imagine what they were thinking.

It was disturbing to drive in Las Vegas afterwards. I found it

almost impossible to imagine what other drivers were thinking —

because they usually weren't thinking at all. Cell phones are a

big part of the problem here — in Mexico it's illegal to drive while

talking on a cell phone, and people, at least in Baja California, don't

do it. Not, I suspect, because it's against the law, but because it's not

sensible. In general, drivers in the States rely on lanes and

signs and signals to avoid collisions with other cars. In Mexico, you have

to rely on a careful anticipation of how others are going to behave — and sometimes of how livestock are going to behave.

On a related note, streets signs are posted very spottily in Mexican

towns, even in big towns like La Paz. You can't navigate by them,

even with a reliable map. This requires stopping often to ask

directions — an occasion for a social interaction that is almost

always pleasant. Why put up street signs when you can have a

friendly interchange with a human being who will tell you how to get

where you're going, and the best way to get there?

Once we got caught in a maze of street construction in Loreto.

There were policemen posted at all the intersections with

detours. When you asked one how to get to Mexico 1, he would

point vaguely in a certain direction — “That way.” Eventually,

that way would lead you to another policemen, who would tell you to go

“up there.” At last you'd find yourself back on a familiar

street, heading for Mexico 1. Why complicate things with

elaborate directions, much less with temporary signs, when there are

enough officers around to give you the part of the puzzle you need at

any given moment?

It should be noted that the police in Mexico do enforce the driving

laws. Contrary to popular belief they don't target tourists, but

they don't give them a pass, either. Noting the presence of

police is part of the acute environmental awareness necessary for

driving in Mexico.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

TODAY’S TIP FOR TRAVELING IN MEXICO

The most important thing to know about everyday Mexican culture is that it’s organized around a system of subtle but highly formal and ritualized courtesies between people. Even when you have business to conduct in Mexico, the situation — at a gas pump, a cashier’s stand in a department store, a roadside taquería — is first and foremost social, not commercial. If you treat a Mexican waiter or merchant or clerk as a functionary, if you get right down to business or generally act as if you’re in a hurry to conclude it, the Mexican is likely to see you, quite correctly, as a barbarian.

Mexicans are accustomed to Yankees behaving like barbarians. They have a defensive reserve when dealing with gringos. We saw pompous middle-aged Yankees, soi-disant sportsmen, ordering dignified waiters and bartenders around as though they were children. The waiters and bartenders took a little extra time doing what they were told, and if you caught their eye in such moments, they would offer the slightest trace of a smile . . . and a shrug. A civilized person can never be humiliated by a barbarian — only saddened, or amused.

But if you take your time, look them in the eye, exchange greetings like a civilized human being, they are more than likely to break out in wide smiles and treat you with an almost familial warmth. If you show them that you’re interested in them, they become interested in you, interested in what you want, interested in helping you get it. The situation has become personal — humane.

The moment of greeting, of establishing a personal contact, can be very brief, but it must entail a perceptible pause, an unhurried ease, a sense that nothing will or should happen until the two of you have sized each other up and shown each other respect. Your Spanish can be dreadful — it’s the timing and the demeanor of the parties that define the interchange.

Mexicans are never servile, but they have a servile mask they can assume when dealing with barbarians. It’s a mechanism for getting through with the interaction as quickly and painlessly as possible. It has a melancholy quality, too — because in truth they are feeling sorry for you. But nothing delights a Mexican more than being of service to a compadre. Accommodation and co-operation are values of the highest order in Mexico — a legacy of its revolutionary history and a necessity in an underdeveloped economy.

When we took our cruise to the Isla Espíritu Santo I left the

lights of my car on. When we got back the battery was dead.

The guy who rents the kayaks at Pichilingue instantly went to his car,

pulled it around to mine and got out his jumper cables. But we

couldn’t get my car into neutral without power and so couldn’t push it

out close enough to the guy’s car to hook the engines up. The guy

went and got his boat battery, which charged my engine enough to allow

the shift to neutral. We pushed the car next to his and soon had

it going again. He never once gave the impression that he was

doing me a favor. When I slipped him 100 pesos afterwards he

nodded gravely but didn’t look at the bill — just tucked it into his

pocket. The gesture had been enough — but the gesture was very

important.

Bargaining in Mexico is a game between equals, conducted not for financial advantage to either party, but for fun. We saw fellow tourists angrily and self-righteously berating a hotel clerk for not honoring some sort of discount coupon, treating the clerk like an imbecile. The clerk, who spoke perfect English, pretended not to understand what they were saying.

But when my sister haggled with a hotel clerk for a reduced room rate by

suggesting, with a face that was a little too perfectly straight, that

her children were weeping and fainting in the car from heat exhaustion,

the clerk laughed . . . and reduced the rate. Once a hotel clerk

told my sister that he couldn’t reduce his rates because it was high

season. “But high season is in February,” she replied. The

clerk looked around furtively, pressing a finger to his lips.

“Tell no one,” he said. My sister laughed . . . and he reduced

the rate. The game had been played well.

Some mornings in La Paz I would go across the street from our hotel to a little food stand in a park, for a cup of coffee. It cost eight pesos and I would always leave the señora behind the counter ten pesos, which she always accepted with a mixture of gracious formality and genuine delight. Once my sister joined me for coffee and when she went to pay for it, the señora felt it was her duty to tell my sister that I customarily left a two-peso tip. I think she was afraid that my sister might embarrass herself, and perhaps compromise my own honor, by forgetting this tiny, infinitesimal courtesy.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

LEAVING LA PAZ

We

hated to leave La Paz but the hotel bill, even with the discount rate,

was mounting and the kids had stories they wanted to tell their dad and

their friends back in Los Angeles. So we packed our frozen fish

in a cooler and headed north again, a prospect made more pleasant by

the thought of re-visiting the towns we'd stopped at on the way down.

There was much excitement about the first night's stop in Loreto,

because of that great pool, but the La Pinta inn there was booked —

which turned out to be a happy circumstance in the end because it drove

us to the Hotel Oasis, which was wondrous:

A great bar where the

kids were welcome to hang out, playing darts and pool, a great seaside

restaurant, hammocks strung up between the palm trees and on the

porches. Nora took advantage of one of them to finish the magical

book Half Magic:

On subsequent days, San Ignacio and Catavina proved to be every bit as

charming as we remembered them. There was even a horse grazing outside our rooms this time at the La Pinta in San Ignacio:

But we made a fatal miscalculation at

the end of the journey. We decided to drive north of Ensenada and

stay at Rosarito, and then take the toll roads across to Tecate, to

save some time.

It was fun to drive by the Fox studio outside Rosarito, where Titanic

was filmed, but the town itself was a nightmare of traffic and hustlers

and tourists. We stayed at a bland motel, whose only advantage

was that it was across the street from a famous old restaurant

specializing in carnitas, slow-roasted pork, which we hadn't run into

often in Baja California (it's not a specialty of the region.) The carnitas was good, and so was a

shrine near the restrooms to Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe:

Driving the next day proved to be a nightmare. The toll road

north was fine and fast, but there were no signs for the turn-off to

the toll road to Tecate and we got lost in the shabby maze of a Tijuana

suburb. Between the hideous condos on the coast and the wretched

poverty of Tijuana, we felt as though we'd entered another

country. It made me think of the old saying — “Poor

Mexico! So far from God, so near to the United States of

America!” Things in this part of Mexico are probably just going

to get worse in the years ahead, and I don't think the condo-sized

Jesus, below, is going to help much.

We eventually made it to Tecate, where we waited for over an hour in a

long line of cars to cross the border. The crossing itself was a

breeze. The U. S. guard, who spoke English with a Spanish accent,

asked us a few questions then waved us through — and suddenly it was

all over. We were back in the States.

All that was left was to miss Mexico — something I haven't stopped doing since.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Lloyd Fonvielle & Harry Rossi]

PESCADORES

The

Mar de Cortés is one of the world's great fishing grounds and we

decided we couldn't end our time in Baja California without at least

one fishing expedition. Morning is the best time to catch fish in

the waters around La Paz — the earlier the better — so we decided to

arrange the expedition through the hotel, which meant we'd get picked

up there instead of having to drive ourselves to a distant rendezvous at some

ungodly hour.

Captain Jack, the hotel's agent for such things, confirmed the wisdom

of this when he told us we had to be ready to leave at quarter to five

in the morning. We would be driving an hour to the beach we'd set

off from. The 4:45 departure and the long drive sounded grim

but encouraging — we would be in the hands of people who were serious

about catching fish.

We stumbled into a van with four other pescadores

at the appointed hour and headed off towards the west, across the

peninsula that forms one side of the Bahía de La Paz. The last

part of the trip took us over bone-rattling unpaved roads to a remote

beach lined with pangas. The sun had not yet risen but Jorge, the

captain of the panga we'd rented, appeared out of the darkness and

rounded us up, loaded rods and a drink cooler into his boat, dragged

the boat into the ocean, helped us on board and set off towards the

Isla Cerralvo, about a half hour away by sea.

Just off the island he rendezvous-ed with two men in a skiff who sold

us our live bait for the day. The two men wore baseball caps and

slickers and had the exact demeanor of Maine lobstermen — with faces

that seemed carved from granite. (People who work the sea tend to become mythological.)

The sun was well up by now, and our taciturn captain finally asked us

what sort of fish we were looking to catch. “Fish to eat,” I

said. “Only fish to eat.” His face lit up, he smiled

happily and began replacing the big hooks on the poles with smaller

ones. I don't know if he was happy because he thought catching

fish to eat made sense, or because it meant he wouldn't have to deal

with the sort of egos that can't be satisfied with anything less than

impressive sporting trophies, but he was incredibly kind to us from

then on, warm and solicitous.

There were several other chartered boats out in the channel looking for

fish — all open pangas like ours. Our captain looked around to

see who was catching what and finally stopped at a likely spot.

He baited our lines for us and spooled them out by hand to the

indicated depth — he said that the channel here was about 60 feet

deep, its bottom lined with rocks which attracted marine life of all

sorts.

It's always so dramatic and mysterious to set a fishing line out into

the ocean — it seems wildly improbable that it will ever connect with

anything swimming down in that alien realm. I was so happy just

to be out on the surface of that enchanting sea that I wouldn't have minded if we never

caught a thing. But almost instantly Nora's rod began to

jerk. “Fish!” shouted the captain, and slowly but surely Nora

reeled in a big, beautiful dorado, also called a mahi mahi, one of the

tastiest fish to be found in any ocean.

Then I hooked something really big — it was all I could do to land

it. But it turned out to be a bonito, a humongous bonito, which

is not a good a good fish to eat. The captain said he would save

it anyway to give to a friend, for shark bait.

Then Nora landed a smaller bonito, which we threw back, and I landed a good-sized tuna — which of course we kept.

By this time Harry had

become seasick. He was truly miserable but the beach was too far

away to land him on — an hour's round trip. Finally he threw up

over the side, said he felt much better, took up his rod and

immediately caught a nice tuna of his own.

Then his stomach turned

on him again and he was more or less out of commission for the rest of

the trip. (This explains why there are no cool photos here of our time out on the water.)

I caught a parga (a red snapper), a great eating fish, and a trigger fish,

an odd-looking flat fish which I'd never heard of before. “It makes the best ceviche,” our

captain assured us — and he was so right. Lee caught a tuna

then, and we felt we'd had a most successful expedition.

Back on shore the captain (sharpening his knife above) filleted the fish and our driver put it in a

cooler in the van. (I gave the captain my big tuna for his family

— we had more fish than we could eat ourselves in several meals.)

In La Paz that afternoon I took our fish to the restaurant at the hotel and asked

the staff to cook up enough of it for dinner for four that evening and

to

freeze the rest. I asked them to make some ceviche out of the

trigger fish. The waiters had to call the chef to identify the

trigger fish, which they didn't recognize, but he beamed when he saw

it. “Ceviche — yes,” he said.

That night we dined like kings — like fishermen. Nora's

dorado

was generally acclaimed as the best-tasting fish of them all, which is

saying a lot when the competition is freshly caught tuna and red

snapper, and the

ceviche made from the trigger fish was sublime. The ocean had

been generous to us, and we took no more from it than we could

use. Life was good.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]

FOOD IN LA PAZ

It's

hard to have a bad meal in La Paz, especially if you stick to

seafood. In fact, if you stick to seafood (and avoid the Burger

King and Applebee's) it's hard not to stumble upon some of the best

meals of your life, just about anywhere.

The fanciest place we ate at in La Paz was the Bermejo, the restaurant

at Los Arcos, our hotel, but we didn't pay fancy prices there because

we dined on fish we'd caught ourselves (an experience I'll write about

in a later post.) The hotel, which caters to fishermen, is happy

to prepare fish you supply yourself, and to freeze any of it you want

to carry home with you.

The simplest place we ate at was the Super Tacos de Baja California

Hermanos Gonzáles, an outdoor stand with a big terrace that's an

outgrowth of a sidewalk stand that got so popular it had to

expand. My sister Lee had some stupendous fish ceviche there,

Harry and I shared some equally stupendous octopus and clam

tacos. (Nora isn't a seafood fanatic and often had quesadillas of

one sort or another.) We never ate better or cheaper food

anywhere in Baja

California. One wall of the place had cool murals (above.)

One evening we took a lengthy walk along the marinas to the south of the malecón

to a medium-priced restaurant called the La Costa, palapa-roofed, right

next to the water. We had super-fresh seafood there and Harry

felt moved to record the crab dinner he ate. “A lot of work,” he

said, “but worth it.”

The Bismark is a rarity — an indoor seafood restaurant back several blocks from the malecón.

The seafood was terrific and the decor was even better:

Harry and

I had dinner one evening at the Bismark II, which the clerk at our

hotel recommended. It's right across the street from the malecón,

with seating on a terrace or back under a high palapa roof. A

charming place with the same great seafood as its parent establishment.

The only bad experience we had dining out in La Paz was at a place right on the malecón, the Kiwi. Lee and I had fine smoked marlin tacos and Harry had a wonderful pescado entero

— a whole fish fried quickly in super-hot oil and then served whole

(but with olives replacing the fried eyes), which Harry also felt moved to

record (see the images at the beginning and end of this post.) But Nora ordered fish and chips and the fish had gone bad

— very bad. There's just no excuse for this in a restaurant

within spitting distance of the ocean, in a town where fresh seafood is

so ubiquitous and so cheap. Foisting a small bit of bad fish on a

child might have saved the restaurant as much as fifty cents, I

suspect, but it lost our goodwill forever.

La Paz is a seafood lover's paradise, not just because there's so much

and such a great variety of it, and not just because it's so fresh, but because of the simple, perfect

ways it's cooked and served. You feel you're eating the same food

the chef would make for himself or herself, or for their families,

prepared with the same unpretentious care and respect.

For previous Baja California trip reports, go here.

[Photos © 2007 Harry Rossi]