Eyes Wide Shut has never been far from my mind since I saw it, twice, on its first release.

I was kind of astonished by it then. Not at all what I expected, a very small film, a chamber piece you could say. So much of it is about the experience of being in rooms, and the intimacy of New York streets at night . . . something I’ve never really seen captured on film before. Even Scorsese’s claustrophobic streets have an epic quality by comparison.

It’s also the best movie about marriage I’ve ever seen. It makes Bergman’s Scenes From A Marriage seem like the platitudes of a first-year psychology student. It makes Woody Allen’s musings on marriage seem like the delusions of a child molester. In fact, I kept wondering what someone who hasn’t been married, for a long time, would make of this film.

And, yes, Nicole Kidman naked is irrefutable proof, in itself, of the existence of God. But what an odd, self-involved sexuality she has — you get a feeling she could be having sex with Tom Cruise, a donkey, a broom handle, and it would all be just the same. And how wonderfully Kubrick uses this quality in the film. She’s so “fuckable” and yet so impenetrable.

But part of the subversion of Eyes Wide Shut is that it always makes you pay for your voyeuristic pleasures — there’s always a twist that makes you self-aware and uncomfortable. There is something intrinsically misogynistic (or at least dehumanizing) about male arousal through purely visual means, and Kubrick draws painful attention to this in the film.

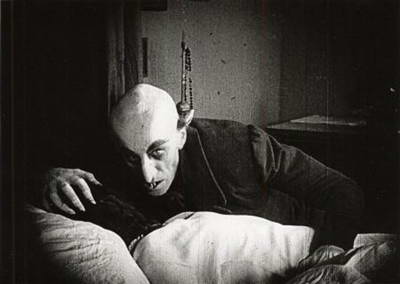

He toys with visual arousal but always undercuts it (shockingly, sometimes, as in the scene above) — because pure, impersonal, meaningless arousal, the goal of most visual pornography, is the threat to the marriage from Cruise’s side of things.

It’s very important that there are no flashbacks to the Naval officer scene when Kidman describes the incident, because her temptation there is more elemental. She feels that Cruise is taking her power as a woman lightly, so she wants to use that power to destroy everything. The flashbacks come only when Cruise thinks about the incident — he reduces it to a visual image of intercourse, of a “one night stand”, whereas what Kidman had in mind was more like Armaggedon.

Several things struck me even more deeply me on a second viewing of the film. One is how brief the Kidman nudity is, contrasted to what I remembered. It’s still startling, mainly I think because you see the whole woman at once. There is no teasing involved. This is very

unusual in a modern film. I have always believed that any nudity which can be done by a body double is by definition pornographic and degrading — it’s about women as body parts.

Kidman is also shot from slightly below, from behind, in very soft light, and her hair is always up. There is an iconic connection to several nudes by Watteau, who was the poet of women’s backs and necks, and to the great nude Venus by Velasquez, at the National Gallery in London, also seen from behind, her face visible only in a mirror.

These shots are contrasted to the Naval officer flashbacks in Cruise’s mind, where you get flashes of nudity, as in a modern movie sex scene.

The Christmas tree motif got clearer. Always warm light, the big old-fashioned colored bulbs . . .

We see the tree in the first scene, when Cruise and Kidman venture out of the home. Thereafter we see it everywhere Cruise goes. At the Zigler’s party, the Sonata nightclub, the coffee shop, the hooker’s apartment, his office at night. And whenever he comes home there is the long tracking shot through the apartment until the tree is revealed. But the last time he comes home, when we see the mask on the pillow, Cruise turns the tree lights off. And in the aftermath of his confession, the unlighted tree is behind him in the living room.

The tree is like a beacon of home, an unheeded reminder everywhere he goes, connected to the daughter — locus of the gifts of home, and symbol, at least theoretically, of the celebration of the birth of a child.

Not an accident that the final reconciliation takes place in a world of Christmas presents, which the child has led them to. “Old fashioned,” says Kidman about one of the “presents”, a baby stroller, which their daughter admires. Yep.

I also realized, and felt really dense not to have spotted it the first time, the significance of the password. The title of a Beethoven opera, but also derived from the Latin word for fidelity. The test at the orgy scene thus becomes very suggestive. Dr. Harford knows the “password for entrance”, but he doesn’t know the “password for the house”. Except that he does, he just doesn’t realize it. Fidelity — the entrance (into marriage) but also the only way of safety for the house, the home.

My friend Andrew Schroeder, then a graduate student in film at NYU, wrote to me about the film:

“What is Cruise’s impulse, when they pull off to the side in FAO Schwartz to talk hushed between themselves? The promise of forever, that he’s learned his lesson, that he’s a changed man and he’ll never go back. Most films would accept that. They’d let him off the hook and say that the ‘happy ever after’ we thought we’d glimpsed in the film’s opening sequences might be waiting just beyond the celluloid lip. Not Kubrick, and not Kidman either. She refuses to talk about ‘forever.’ She refuses to let Cruise off the hook. It’s as if she’s telling him, without saying it in so many words, that the Other must be re-encountered at every turn. The second you think it’s over, and you can just cruise on your expectations and your memories, is the second that you approach Armageddon at top speed.”

That’s an excellent summary of the denouement, I think, and it’s connected to a sense of some absolute limit to intimacy that haunts Kubrick’s film. No matter how many barriers you bust through, and you bust through a lot in a long marriage, there is always one more, and it’s always different from the last one, and bewildering, and apparently insoluble. It’s not just about the Otherness of the opposite sex, it’s about the Otherness of any other human being, and when you get right down to it, the Otherness of yourself, the insubstantiality of the self.

We need the illusion of a substantial self in order to function, but it is an illusion, as life keeps proving, so how do we keep on functioning? In part it’s by accepting a certain loss of control over our own identity, and in part this is made bearable by submission to a “higher” order, the social context, the family context.

The child in the film is very important, though it’s wonderful and courageous that Kubrick makes no overt appeal to this aspect of things. The closest he comes is when the child asks for a dog for Christmas. “He could be a watch-dog,” she argues. She feels the threat to the home that is happening, but her terror is beyond articulation.

Marriage, existential marriage with a perpetual Other, thus becomes an avenue for the survival of identity — the larger identity that can be sustained because it is not rooted in the chaos of personality, but in an idea, of fidelity, and in the flesh of a child that somehow shares the identity of the Other.

It is one way of addressing Nietzsche’s notion that the ability to make and keep a promise is the only thing that makes us human. But it has to be a transcendent promise, unto death — like the sacrifice of life for a cause, the sacrifice of sexual freedom, of autonomous identity, for a child. Nietzsche would argue, of course, that such servitude is the only freedom there is, such as it is.

Kubrick doesn’t draw any simple moral from his tale. Kidman won’t say “forever”, since “no single night, much less a single life, can be the whole truth about anything”. Like Nietzsche, Kubrick looks at the actual forces at play, describes the stakes unflinchingly, and leaves us to our terror at it all — though perhaps a little better equipped to play the game.

Kidman’s last line may be deeper than it seems. In fucking, the metaphor of blurred, surrendered identity is constantly reestablished, the consolation and the terror of it constantly renewed.

All of Eyes Wide Shut, from the title onwards, echoes with such suggestive ambiguity. For example, the soundtrack of the film is interesting to play on its own — it really captures the creepiness and off-centered mood of the whole film. It occurred to me that, for all the visual references to Christmas in the film, there is no Christmas music at all until the last scene — a Muzak version of Jingle Bells. Another of those subliminal calculations that keep us, and the

world of the film, off balance.

Most of Kubrick’s work has always left me cold. It strikes me as exhibiting a sort of puerile moral nihilism. There is little at stake in Kubrick’s films — unless he is being funny — except a passing frisson, and maybe some self-pity.

Paths Of Glory is a partial exception to this rule. It’s worth remembering that the actress at the end of that film, in the scene (above) which is offered as a kind of counterbalance to the moral abyss we’ve just been gazing into, the single note of humanity and hope, is the woman Kubrick would marry soon afterwards . . . and whose subsequent life with him must have inspired, or at least informed, his last film.

Below is Kubrick’s wife to be, Christiane, on the set of Paths Of Glory, with Kubrick and Kirk Douglas:

Eyes Wide Shut is the only film he made based on something he had first-hand experience of — a 40 year marriage. His reclusiveness, and this film, suggest to me that this marriage, his family, were the only things he ever found meaning in. (And by meaning I don’t mean happiness.) This is an idea he was far too skeptical to state lightly or prematurely, and there is something exquisite in the fact that he died the day after he delivered the film. He had to, in a way.

Kubrick’s will, and life, and actual life’s blood are on the screen here. He killed himself making the film — he cared himself to death. That is the only absolute conclusion we can draw from it, and that is the resonance in it we respond to. Let a better filmmaker put something better in its place, make something with more resonance — more “meaning” — on the subject of men and women and marriage.

Certainly, up until now, no one ever has.

I’m still in shock that Kubrick made a movie like this — one of the few from my lifetime which will survive far into the 21st century. What a way to go out.

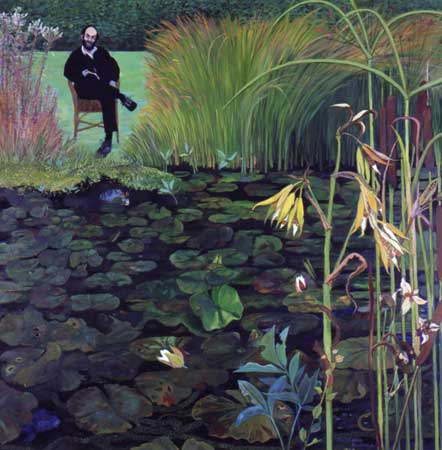

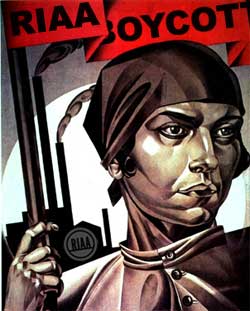

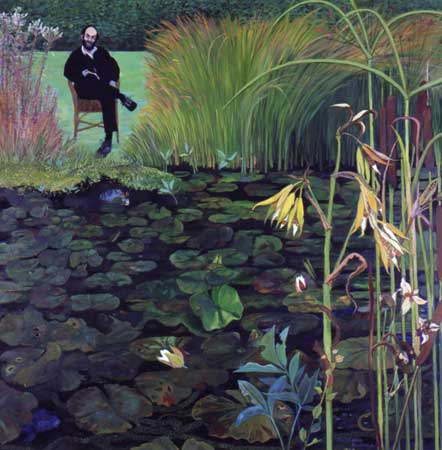

Below is a painting by Kubrick’s wife, called Remembering Stanley: