Dornan's is a funky old recreational complex located inside the Grand Teton National Park not far from Jackson. It's been going since about 1948 and has become a local institution. It has cabins and a couple of restaurants and a grocery store and every Monday night it hosts a hootenanny in a roofed-over dining area next to its “chuck wagon” — an open-sided kitchen with grills and barbecue pits where you can buy dinner and beverages. Around it are picnic tables, including one inside a teepee.

Local musicians sign up to play a couple of songs each at the hoot, and most of them are quite good. On our second night in Wyoming the musicians in the John Carney birthday crowd — J. B., Hugh, Eli and John himself — signed up to play a few sets.

The “backstage” area, a lawn behind the dining/performing structure, where I mostly hung out because you could smoke there, was quite a scene, with musicians tuning up, showing each other new licks, or going over the songs they were about to play.

Corinne Chubb filmed the Carney Cowboy Band numbers on her tiny HD camera. Here are a couple of the songs they played, up on YouTube:

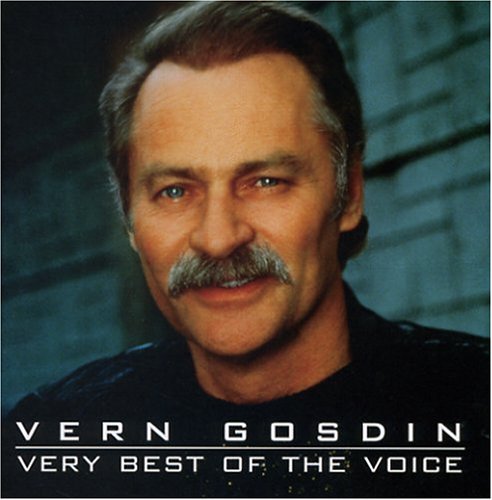

This is a new song by J. B., and one of the best he ever wrote — a country waltz which, like many country love songs, is about older folks, married folks, keeping the flame alive. To me, it's an instant classic — as good as any country waltz ever, and that's saying something.

This is an old song, written by Hugh in 1970. Hard to explain how important it is to those of us who met and first heard it back then — a kind of anthem which has carried us along together through the years . . . so many years now that it doesn't just take us back but forward as well, to the next time we'll hear it, and the last time we'll hear it. Everyone's still at sea, and it's still all right — always will be.

There was one other lovely moment that night, not recorded, when a young girl with a guitar and a sweet voice sang “How Great Thou Art”. There are a lot of young (as well as aging) hipsters in the Jackson area these days, but an older West and an older America are still present. Many folks in the audience were singing along quietly to themselves with”How Great Thou Art”. They looked as moved by it as I was.

The Tetons loom up majestically behind Dornan's, and only a religious song makes sense of them — you find yourself thinking, “I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills . . . whence cometh my help”. An old line that still resonates with a hard-won wisdom, at least out in God's country.