Well, the rifleman’s stalking the sick and the lame,

Preacherman seeks the same, who’ll get there first is uncertain.

— Bob Dylan, Jokerman

To call Bob Dylan the greatest Christian poet of the 20th Century (and the 21st Century so far) is probably to damn him with faint praise. There just weren’t that many great Christian poets in the 20th Century. His Christian poetry, however, is more alive and vital than the work of other poets with greater reputations, like Auden and Eliot, who were nominally Christian but whose poetry is less concerned with expressing passionate faith than with charting the ennui of a faithless age.

And Dylan is not quite a poet in the modern literary sense — his words don’t live on the page, only in conjunction with the music that is inseparable, expressively, from those words, and mostly only in his own voice. Very little of his poetry survives in cover versions of his songs — although it can. (Hendrix knew how to sing Dylan, and Dylan’s Gospel songs come gloriously alive in the versions of them by black Gospel singers collected on the recent CD Gotta Serve Somebody — most other versions fail because the artists who attempt them don’t realize how deeply Dylan’s work is steeped in the blues, or have no great feel for the blues themselves.)

Dylan wrote two types of Christian songs, one type that fits more or

less directly in the Gospel tradition, however quirky his take on that

tradition might be, and one type that follows the image-collage strategy of

another American tradition, what might be thought of as Whitman by way

of the Beats.

Jokerman is of the second type. It’s a powerful evocation of the image of Jesus, or rather the images of Jesus, but it’s hardly a catalogue of familiar icons. It’s more like a passionate torrent of Dylan’s own various imaginings of Jesus, his own various attempts to comprehend him. The momentum of the work seems to be deeply personal — not an intellectual or aesthetic meditation but a desperate attempt to record a racing stream of thought in which one image of Jesus is instantly rejected as insufficient, replaced with a corollary or opposing image. The ultimate effect is a kind of lyrical portrait in the round — but a portrait in which the subject just won’t sit still.

Standing on the waters casting your bread

While the eyes of the idol with the iron head are glowing.

Distant ships sailing into the mist,

You were born with a snake in both of your fists while a hurricane was blowing.

Freedom just around the corner for you

But with the truth so far off, what good will it do?

The first quatrain presents us with the image of an almost pagan figure — a terrible Jesus who stands in conflict with the ancient false gods, the iron gods. Dylan, too, was born with a snake in both of his fists and did not reject the terror of the predicament. (Just try to imagine Auden or Eliot with their hands full of venomous reptiles — they would certainly faint dead away, once they realized that the snakes weren’t metaphors.)

But the last couplet jolts us back to a different kind of complexity. Jesus, the lord of nature, the destroyer of false idols, is not free like the gods of old. His power is useless in the absence of truth within the hearts of men. This is the difference between Jesus and the other, older gods. His power and his freedom count for nothing if they can’t be shared, communicated, translated into the language of simple men. This fact defines his mission, his incarnation.

Jokerman dance to the nightingale tune,

Bird fly high by the light of the moon,

Oh, oh, oh, Jokerman.

Why “Jokerman”? Because the paradox of Jesus’s mission is like the paradox of a good joke — too surreal to be taken seriously by a slow-witted humanity. Many of the climaxes, the final unexpected twists, of Jesus’s parables are like the punchlines of jokes. Laughter is not an inappropriate response to them.

In Dylan’s recording of the song, listen to the yearning, the hopelessness in Dylan’s voice as he sings the last line of the chorus above. He is bemoaning the limits of language and music and human thought.

Well, the Book of Leviticus and Deuteronomy,

The law of the jungle and the sea are your only teachers.

In the smoke of the twilight on a milk-white steed,

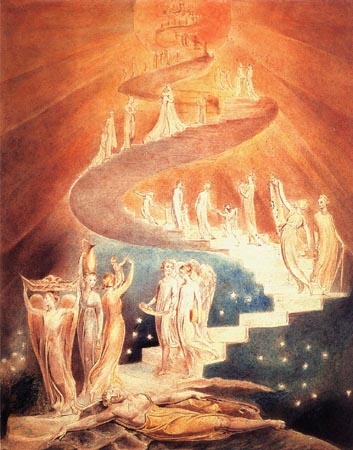

Michelangelo indeed could’ve carved out your features.

Resting in the fields, far from the turbulent space,

Half asleep ‘neath the stars with a small dog licking your face.

In the first couplet above, the paradoxes are almost resolved. Jesus has come to fulfill the law and the scriptures, to reconcile them with the laws of nature. The message of Grace will find unsentimental expression in light of a harsh view of this world and its inexorable destructiveness. The issues, the stakes, won’t be fudged. (See the couplet at the beginning of this post.) In the next couplet above, Jesus is exalted, aestheticized — worshiped as he’s worshiped in art:

But Dylan can’t leave Jesus here — a figure carved in marble.

The last couplet above startles like a bolt of lightning — because

suddenly Dylan is back imagining Jesus as he walked the earth, sleeping

rough, on the road between two villages, as he must have done on so many

nights, getting just a little rest, and alone, probably grateful for

the affection of the little dog who undoubtedly showed up at the

disciples’ campfire looking for a handout. This is a good man,

the dog senses — he won’t kick me.

All the allegories and all the art fade away. The image of Jesus

won’t be fixed by any convention. It always returns to the dust

of the earth and to mystery. There are no “answers” in Jokerman —

just a question . . . who is this guy, who is this joker? It’s

the question Dylan is asking himself, and it’s unanswerable.

Lyrics copyright © 1983 Special Rider Music