[Photo by Carl Van Vechten]

The

poetry of a play by Shakespeare is characterized by an almost

supernatural density of imagery and invention, wordplay, wit and

insight. Though designed to fly by in two hours' traffic

upon a stage it simply cannot be absorbed fully on a single hearing or

reading, composed as it is of a torrent of miraculous phrases and passages that

repay continual study. The sheer abundance, the sheer generosity

of it is overwhelming.

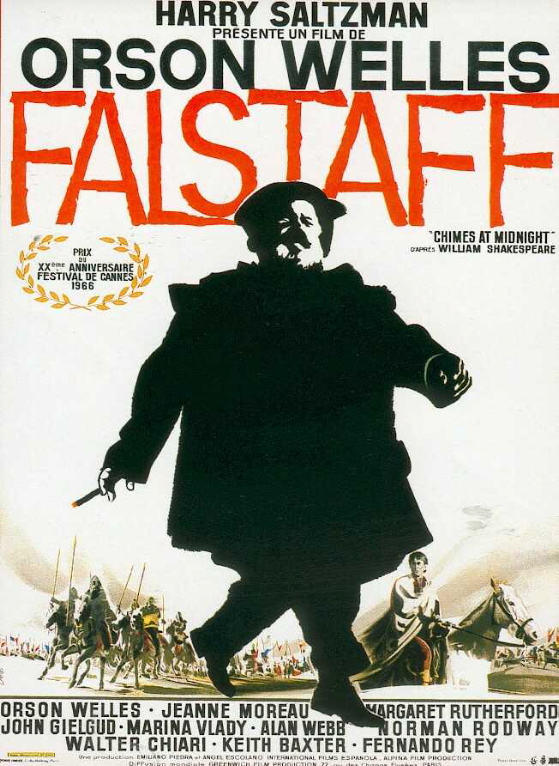

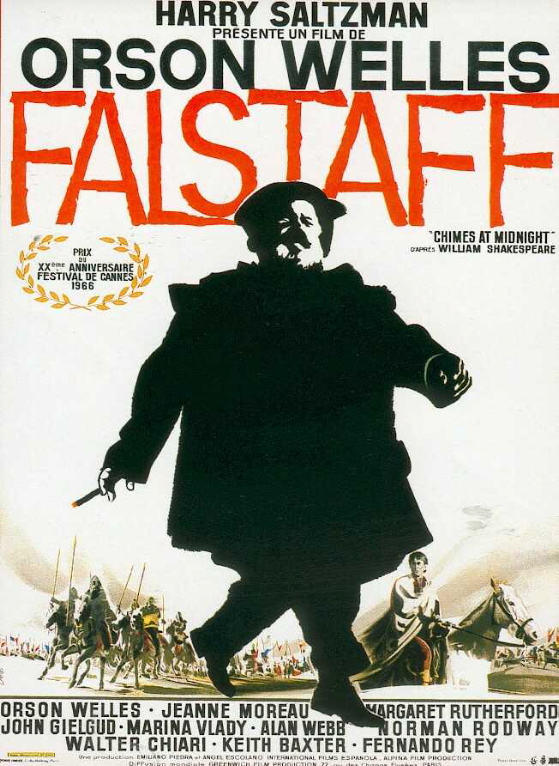

Orson Welles completed three films based on Shakespeare plays — Macbeth, Othello and Falstaff (Chimes At Midnight).

His interest, as it became clear over time, was not simply in mounting the plays within the cinematic

medium but pushing the medium to supply a cinematic equivalent to

Shakespeare's poetry. In Falstaff,

I would argue, he finally succeeded in this ambition. In the

process he completely rethought the approach to cinema he employed in

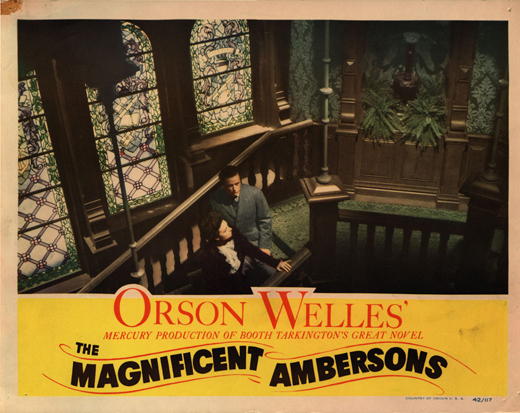

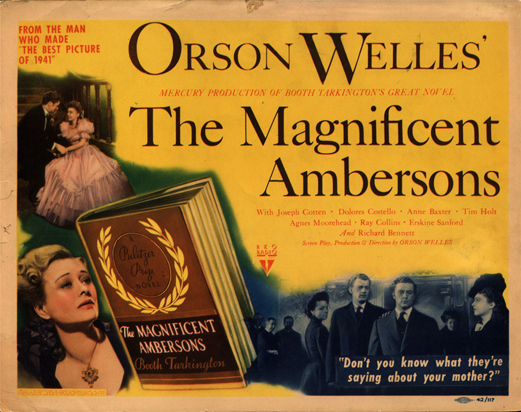

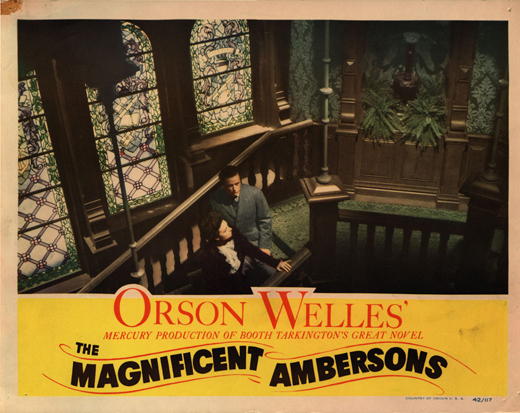

his early masterpieces Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons.

Citizen Kane, though

dominated aesthetically by scenes shot in deep focus and playing in

long takes, in fact employs a grab-bag of cinematic techniques —

process shots involving backscreen projection, models and matte

paintings, double-exposures, faked newsreel footage. In The Magnificent Ambersons,

Welles experimented with even longer and more elaborately choreographed

single-take scenes, some of which were cut up by Robert Wise at the

behest of RKO when they took the film away from Welles — but Welles

also included pictorial trick shots that violate the aesthetic of the

single-take scenes.

With The Stranger, Welles was

trying to work within the boundaries of a more conventional studio style,

but he eschewed trick shots almost entirely and included one long,

stunning single-take scene made with a crane on tracks in a forest. In The Lady From Shanghai

he tried his best to stick to location photography and to incorporate

long single-take scenes, but the film was so meddled with by Columbia

that we don't have a clear record of Welles's vision for the film as a whole.

All this was prelude to his first Shakespeare adaptation for film, Macbeth,

made cheaply and quickly for Republic Pictures. The 23-day

shooting schedule meant that Welles had to limit his technical

ambitions for the film. His increasing fascination with long

single-take scenes resulted in one extraordinary feat — a

10-minute shot which records the entire episode leading up to and including the murder of Duncan

and the arrival of Macduff, who discovers the crime. It plays

out on several levels of the studio set, covered by pans, tracks and

crane moves.

There are two other less extraordinary single-take scenes of some

length. One records the episode in which Macduff learns of the

deaths of all his “pretty ones”. This is taken from a fixed

camera position on a studio-exterior set without great spatial

interest. The four actors involved move about in ways that often

feel arbitrary in order to create different groupings of the characters

and heighten the complexity of the shot. The other shot records the

scene in which Macbeth, on the parapet of Dunsinane, learns of the

approach of Macduff and his armies and then moves inside to discuss

Lady Macbeth's mental health with her doctor. Again, the studio

sets here don't offer much spatial complexity and the choreography is not

especially dynamic.

Two shorter scenes involving dynamic camera moves are more

powerful. In one, the camera starts on a close-up of Macbeth, left

alone in the banqueting hall, and moves with him, pulling back, as he

races outdoors to the top of a rock and summons the weird

sisters. This is followed shortly by a high crane shot that swoops down

slowly onto the figure of Macbeth and ends in a close-up on his

upturned face.

The rest of the film employs a more conventional editing of shorter

shots. Some of these shots are visually arresting, involving

dynamic camera moves and angles, but many more are merely

utilitarian. There are a few interpolated shots taken on real

exteriors, a couple of shots employing matte paintings and, in the

final battle scene, a series of shots manipulated with optical

zooms. Taken as a whole, the visual strategy of the film is

chaotic.

When he came to make Othello

a

few years later, Welles said he planned to shoot it all on built sets

and in long takes — making it, in effect, an extension of the approach

he took with the long single-take studio-bound scenes in Macbeth. He had been disappointed with the execution of the sets he designed for Macbeth, which do indeed look pretty cheesy most of the time — but he had a superb designer for Othello, Alexander Trauner, who sketched out elaborate sets for the film, meant to

be built at the Victorine Studio in Nice. Welles was thrilled

with the sets Trauner envisioned and always spoke of them wistfully in

later years.

All of Welles' plans for Othello had to be abandoned, however, when the film's

original financing fell through. Welles could only afford to

shoot in real locations, few of which were suitable for the entirety

of a given scene. In addition, limitations on equipment and the size of the crew

meant that he could not shoot long takes, which, as he explained,

require the technical resources of a large studio production unit.

These problems altered Welles' whole aesthetic approach to the film,

since he would not only have to use short takes more or less exclusively but he

would also have to match shots taken in disparate locations within a

single scene.

His response was masterful. He concentrated the full power of his

visual imagination on the individual shots — almost all of which, however brief, record

deep, dynamic spaces and boldly choreographed movement — and used rhythmic, musical editing in an attempt to unify them

into a coherent artistic whole.

The result was impressive but not uniformly successful. Clearly Welles was improvising

from day to day, sometimes desperately — the production was halted on numerous occasions when

funds ran out, necessitating changes of locale and the loss of actors

due to conflicting commitments. The “music” of the editing was

something Welles could not always control expressively — often he was

just trying to keep the beat, to bridge extreme gaps in continuity.

But necessity had led him to new possibilities of invention. He would deploy them spectacularly in Falstaff.

In that film he would shoot to the music of the editing he

envisioned, without the technical vexations created by Othello's near-fatal financial emergencies. There would be no long, virtuoso single-take scenes

but each shot would be dense, beautifully choreographed, with its own

dynamic spatial complexity. These shots would be utterly

involving in themselves

— and Welles would be able to preserve a sense of spatial continuity

from shot to shot to a degree that had not been possible on Othello — but the images would flow by with a relentless momentum, regulated by the metric of the editing.

Welles would not linger on the rich poetry of his individual shots but

race through them — as Shakespeare races through the rich poetry of his texts.

The great battle scene in the film offers the most extraordinary

vindication of Welles's approach. Though made up of scores of

short shots, each is like a film within a film — bold, dynamic,

involving. You feel you could linger on every one of them

indefinitely.

When he was 19, Welles wrote this about Shakespeare — “His

language is starlight and fireflies and the sun and the moon. He

wrote it with tears and blood and beer, and his words march like

heartbeats.” It's not too much to say that in the images of Falstaff Welles found a cinematic equivalent to Shakespeare's poetry — a true visual complement.

Which is to say that Welles took cinema as far, or nearly as far, as Shakespeare took the

English language — and that's as far as anyone has ever taken it.